Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday, 3 October 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Jeewa Siriwardena

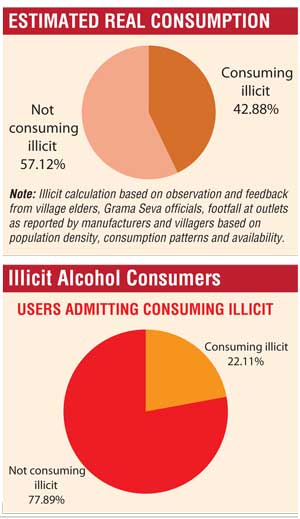

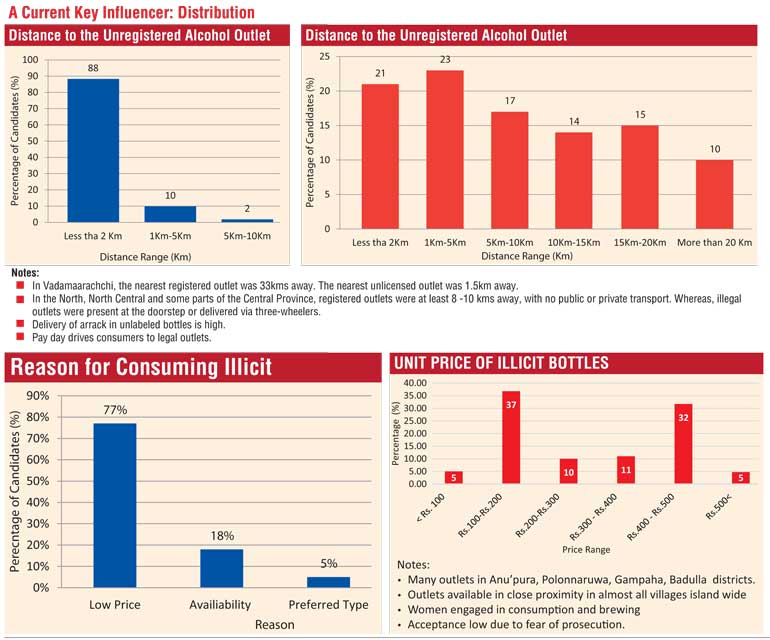

In our first report titled ‘Making Sense of Alcohol Policy’, we detailed the spread of illicit alcohol, the abuse of spirits and its impact on society and women. As alluded to in the report, we established that low price and easy distribution are the key elements that drove growth in illicit alcohol, with over 65% of participants having access to an illegal outlet within a two-kilometre radius from their residence.

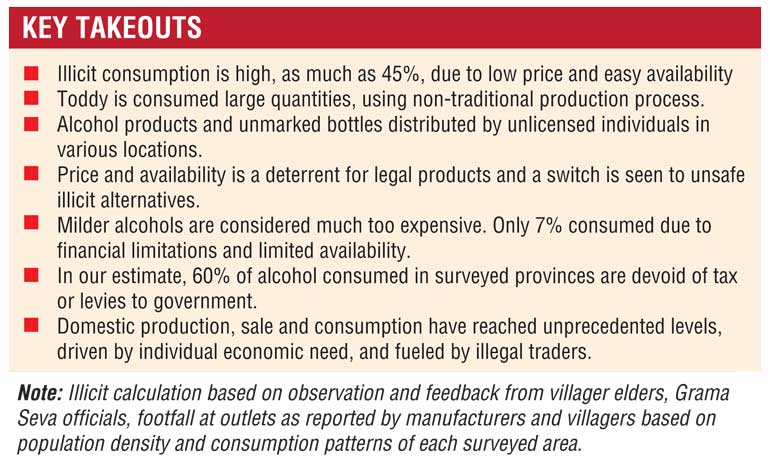

Since August, we had the opportunity to grow our engagement to 5,000 families island-wide, and the picture remains as bleak as before or even worse. Close to 70% of households admit to consuming alcohol, with 93% exclusively consuming spirits and 45% of them consuming illicit alcohol or kasippu.

Throughout the survey, we had the privilege of engaging families across Sri Lanka from all ethnic groups and cross sections of society and industry. Whilst we focused predominantly on underprivileged and working-class rural sectors, illicit alcohol didn’t discriminate and pervaded all communities island wide.It had even reached the hands of senior Government executives, engineers of reputed private firmsin Colombo – shedding new light on the growth and reach of illicit. Just under 28% of spirits consumers admitted to consuming illicit products, but with an average of four outlets per village and with footfall numbers as reported by them, we estimate this number to be 45% and potentially even higher.

A bottle of kasippuretails for as low as Rs. 200 in some parts of the country. For 80% of the surveyed base, a kasippu outlet was within walking distance from their residence, whilst the nearest registered wine store was situated over 10 kilometres away for more than 62% of the base. The equation therefore becomes simple. A rural consumer will not seek public transport or use his own to travel 10 kilometres to purchase a 750ml bottle of arrack or any other legal spirit that costs an average Rs. 1,000, when he can purchase a bottle of illicit for much cheaper at a mere stone’s throw away. The legal produce is expensive, it is difficult to access and bound by operating hours; none of these factors hamper the illicit trade.

The North Central, North Western and Central regions presented the highest incidence of the illicit trade, with some localities such as Kebithigollewa and Waduwawela having as many as ten outlets. In Polonnaruwa, farmers received kasipputo their fields in tea pots, as they lamented that high price of legal products and little value for money drove them to consume illicit. Residents in Hingurakgodaconfirmed that multiple illicit outlets were present in the region, but that Police and Excise officials did little to apprehend offenders adding that they worked together. Even the small-scale domestic kasippubrewers reported daily revenues of more than Rs. 7,500, showcasing the extent of incomes lost to government.

As stated above, low price and easy availability of products drive consumers towards illicit, and government will need to take remedial measures to address the resultant issues of loss of revenue, health and the breakdown of law and order. Government revenue from the alcohol industry has come down in recent times, and this is due to consumers shifting towards illicit. This is clearly reflected in our observations and the feedback we have received from consumers.

Sri Lankans, it appears, have an almost inseparable affinity towards the consumption of spirits. Many labourers and daily wage earners believe that consuming spirits removes pains and aches from their bodies, as some even termed it medicinal. Despite the widespread consumption of illicit and legal spirits, less than 10% of respondents admitted to alcohol-related health problems, whilst related physical and mental abuse rose to 15.7% thoughthe real rate is estimated to be above 28%.In the arrack segment, a staggering 85% purchased the 180ml flasks (kale bothal), with some consumers chugging as many as three bottles by the middle of the day. The flasks are popular amongst most consumers as they are cheap, “presents great taste” and is easy to carry undetected they said.

We observed that the 180ml arrack bottle was consumed individually in a single serving. Whilst arrack is no doubt a better alternative to illicit, this pattern of consumption of the 180ml bottle is clearly hazardous to health and constitutes abuse alcohol abuse. Up to 80% of spirits consumers drink arrack. We observed that arrack is often sold via unauthorised mobile outlets upon order in the Jaffna, Badulla and NuwaraEliya Districts.

Of the 5,000 families polled, a mere 7% admitted to consuming beer, the mildest form of alcohol. Beer consumption was reported mainly from Colombo and suburban areas. Though a significant number of respondents expressed their liking to the product it is far too expensive and unaffordable they stated. Consumers had a clear understanding that low alcohol content was a safer alternative, but remarked that it did not make economic sense due to price. Though an illicit alternate was available for every form of alcohol, interestingly there was none available for beer.

Up to 46% of respondents admitted to consuming toddy, with a cup costing as low as Rs. 50. However, on average only 35% of produce is reported to the department, as many tappers choose to use it for private consumption and sale.

Based on our current findings, we estimate that up to 60% of alcohol consumed in Sri Lanka is illegal and does not bring any form of revenue to the government, and presents severe health hazards to consumers. There is no separating alcohol from Sri Lankan society; it is engrained in every aspect oflife. In this, Sri Lanka is no different from the rest of the world. Through our study, we have concluded that it is our reluctance to accept ground realities that has exacerbated the situation. Instead offocusing on prohibition, our policy must focus on reducing or even eliminating harmful consumption, bring backconsumers to the legal fold and within the legal fold, from hard to soft alcohol, to ensure a safer alcohol culture and safeguard government revenues andlaw and order.

Distribution and pricing based on alcohol content have beenadopted in developed markets to control harmful consumption, and it would seem ideal for Sri Lanka to adopt asimilar model with regards to its policy.Despite the widespread prevalence of illicit alcohol, the consumers’ preference towards safer legalproducts was apparent. Based on feedback, we begun asking respondents if they would switch to legalalternatives if price was no longer an inhibitor and the response was overwhelmingly positive.

We must also put a stop to turning a blind eye on women and their relationship to the alcohol trade.Whilst a significant number of women are victims of alcohol-related mental and physical abuse, theyforma major part of the value chain in terms of production and consumption. Outside the Colombo region, we encountered closeto 400 women who were engaged in the production and sale of illicit alcohol at theirhomes. These are factors we need to consider in our efforts to develop a safer drinking culture in thiscountry.

Our survey aims to engage 9,600 families island wide. The 5,000 families we have met with in various parts of the island present diverse economic and social challenges and expectations. For instance, education came to the fore in the Matale and Kegalle Districts, whilst agriculture and animal husbandry presented challenges and opportunities in the North Central and Northern Provinces. Residents of the Uva province required skills development and training, and requested our assistance to connect them with government or private agencies that could help them. Diverse avenues of concerns and needs.

Alcohol abuse was the common problem that besieged every province, and in every one of them illicit alcohol laid waste to families and lives driven by price and availability. Successive government policies have given rise to this problem, and it is only policy and practice that will drive us out of it. We hope that the Government would take due note. Looking forward, the Government must also take steps to combat the rising incidence of drugs which is growing at a rapid unprecedented rate in most parts of the island. Drugs will put our troubles with alcohol abuse into shame if we are not proactive.

(The writer is an education professional and Chairperson of Social Development Network, a not-for-profit organisation engaged in research and engagement to help design policy and action to uplift economic and living standards primarily amongst women. She can be reached at [email protected].)