Friday Feb 27, 2026

Friday Feb 27, 2026

Monday, 28 January 2019 00:06 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Raj Gonsalkorale

Before discussing whether the proposed new draft constitution as submitted to the Constitutional Assembly by the Panel of Experts has as its real objective the reinforcement of the ancient Tamil homeland theory, or whether it is a pathway to address the long standing “Tamil” issue, the above stated citations need to be noted.

Firstly that a constitution that is unitary is basically one where power rests at the centre and that the opposite of this is federalism, where power rests both with the centre and defined provinces or states.

In this context, one could say that Sri Lanka has had some form of federalism since the introduction of the provincial councils in 1987 considering that power or some powers, were included in national lists, provincial lists and concurrent lists. Some political powers were devolved to provinces.

The new draft document reportedly states that “Sri Lanka (Ceylon) is a free, sovereign and independent Republic which is an aekiya rajyaya/orumiththa nadu, consisting of the institutions of the Centre and of the Provinces which shall exercise power as laid down in the Constitution.”

The draft document appears to remove the ambiguity with regard to the question whether Sri Lanka is a unitary country or a united country, and it clearly articulates that it is a united country (aekiya rajya) and not a unitary country. However, unless the word “united” in the context of situation in Sri Lanka is clearly defined, the word will have no legal bearing unlike the word “unitary”. The implication of being a “united” country will be that Sri Lanka will have a federal system although it will not be referred to as such, for now.

In this context, the next issue is whether calling Sri Lanka a Federal Republic is fraught with the dangers that some have been canvassing for a long time saying federalism could lead to some provinces establishing themselves as independent sovereign states.

The inclusion in the draft document that “No Provincial Council or other authority may declare any pa rt of the territory of Sri Lanka to be a separate State or advocate or take steps towards the secession of any Province or part thereof, from Sri Lanka” may assuage fears that some have about the emergence of a separate State.

This clause, provided it is ultimately included in the body of the Constitution without any provisos or linkages to any other clauses, meaning, it is stated as a standalone fundamental legal provision without any qualification and that it cannot be changed under any circumstance, could assuage those who are suspicious about the intention of the drafters of the Constitution.

However, it is not clear whether there is absolute unambiguity about the amalgamation of two (or more) provinces as this is a fear amongst many Sinhala people that unless such unambiguity is there, it could lead to a disproportionate, in terms of land mass, sea front, and population, unit being created as it was soon after the 1987 Accord.

Now, while returning to the main objective of this article, it needs to be stated that the draft document, as far as the writer is aware, has not been released to the public and many, including the writer is basing their points of view on second hand information from others. This situation is not a healthy one for informed discussion and debate and hopefully, the government will release the draft document to the public for open discussion.

The writer wishes to argue that the new Constitution, or whatever is known of it, does not address the “Tamil” issue, but that it will, over time, exacerbate it and create more disharmony amongst Sri Lankans. At the heart of this argument is that it creates further divisions amongst Tamils by making some Tamil more equal than others.

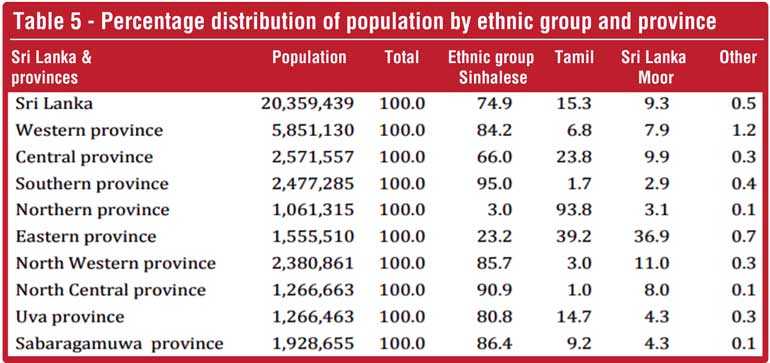

In contemporary Sri Lanka, only two provinces have a Tamil majority. The Northern Province, which has a Tamil population of 93.8% and the Eastern Province, a Tamil population of 39.2%. The statistics quoted in this article are from the Census conducted by the Department of Census and Statistics in 2012. Nationally, 51.5% of all Tamils in the country live in the Northern and Eastern Provinces, while 48.5% live outside these two provinces. In the proposed structure, 48.5% of the Tamil population will live as minorities in seven of the nine provinces in the country as shown in the table. In the Eastern Province, the Tamil population is a minority if the Sinhala and Muslim population is combined.

If the intention of the new Constitution is to devolve power, or some powers, to the provinces and make them more independent (of the centre), and provide avenues for greater self-determination, from a Tamil perspective, their minority status in the seven provinces and in the Eastern Province (when the Sinhala and Muslim populations are combined) will not provide the freedom and the flexibility their brethren will have in the Northern Province. So, in this sense, a class of Tamils who are more equal than others (in the rest of the country) will be created.

If the “Tamil” issue arose on account of domination and discrimination by the Sinhala majority, then, a new Constitution based on this draft will change nothing except in the Northern province as the status quo in regard to the majority position will remain elsewhere irrespective of constitutional provisions that prohibit discrimination by race, religion, gender, disability, etc. under any circumstance, as already enshrined in the current Constitution.

In respect of the “Tamil” issue, granting greater devolution of powers to provinces will benefit the Tamils in the Northern Province and to a lesser extent the Tamils in the Eastern Province. Other Tamils will have to work out how best they could share power with the Sinhala community and other communities and work for the betterment of all communities. The question that springs to mind is whether this is in fact what the constitution model should be for the entire country, and what kind of constitutional structure would provide the foundation for a society which accepts and respects the diversity of the country.

If the introduction of a Constitution as proposed also introduces an element of dichotomy of purpose, and consequently, suspicion, then, the objective of the exercise should be scrutinised, and critiqued.

The doubts that are there whether the new constitution will address the “Tamil” issue, which basically has been the reason since independence for the conflicts, including the armed conflict, one cannot discount the premise of the title of this article, that the objective of the exercise has been to reinforce the ancient Tamil homeland theory which could lead to an eventual separate State combining the Northern and the Eastern Provinces. No doubt this premise will be denied by the advocates of the new Constitution.

However, what cannot be denied is the suspicion that has been created by proposing a Constitution that does not appear to provide a structural solution to address issues faced by the broader Tamil population domiciled throughout the country. It provides a political solution for Tamils living in the Northern Province, and to a lesser extent to Tamils living in the Eastern province. The Tamils in the Eastern Province may argue that most Muslims in that province are linguistically linked to the Tamils, and therefore together they would be able to address issues affecting them in the province. However, should political dynamics lead to a coalition with political parties that are largely Sinhalese, then, the Tamil community would be a minority in the province.

In the context of the argument presented, a counter proposal for a structural solution to address “Tamil” issues would be to share power at the centre. The proposed bi-cameral legislature needs to be retained and strengthened to ensure minority rights are protected with veto powers for minority representatives over legislation that impacts on their rights. Provincial councils may be retained to better coordinate the implementation of national policies.

Devolving of Police and land powers should not be part of such a model although, it needs to be recognised that the community in any geographic area needs to comfortable with the Police force as the purpose of the police service is to uphold the law fairly and firmly; to prevent crime; to pursue and bring to justice those who break the law; to keep the peace within the community; to protect, help and reassure the community; and to be seen to do this with integrity, common sense and sound judgement. Land powers should remain with the central government although a consultative process with the provincial councils should be introduced.

Whatever the structure of a Constitution is in relation to power devolution, there are major issues that need to be addressed. One such area is women’s rights and the economic backwardness of women in Sri Lanka. Some women’s rights activists have pointed out that there had been a productive consultative process leading up to the drafting of the new Constitution, but that they are very disappointed that none of their proposals had made it to the draft.

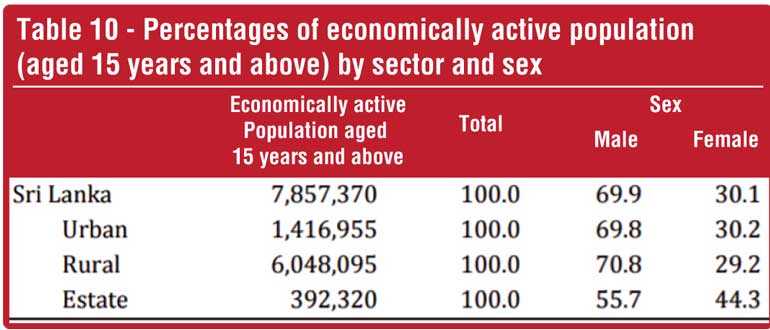

The table is very relevant in this regard. It shows the disparity between economically active males and females in urban, rural and estate sector settings. The estate sector shows the highest percentage of women who are economically active. Country-wide, only 30.1% of females are regarded as being active, although the country does not record females who are doing unpaid household work as being economically active.

This example has been shown to demonstrate that issues similar to this are ones that should have been considered in the draft constitution. It may include these, but as the draft is not in the public domain at present, it cannot be stated with certainty whether issues such as these have been considered and appropriate provisions included in the draft.

While there is acknowledgement that a consultative process was part of the drafting process, many who participated in that process have complained that their representations and proposals are not include in the draft. In any event, introduction of a new constitution cannot be and should not be rushed. If there was a preceding process, there has to be a post drafting process as well where the draft should be subject to public discussion. If such a process is not followed, it will cement the suspicion that the new Constitution is aimed only at reinforcing the Tamil homeland theory, and it is another step in the direction of eventual separatism.