Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Wednesday, 12 June 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The world stands on the brink of a fourth industrial revolution, where dramatic changes in technological advancements will have profound impacts on the future employment landscape and skill requirements. This means that engaging in lifelong learning—be it at school or at work—to anticipate and prepare for future labour market demands is of paramount importance.

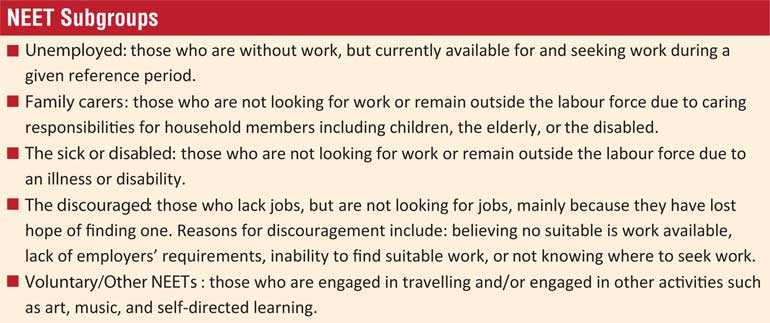

In this context, the presence of a large population of youth not in education, employment, or training (NEETs) is a major cause for concern. NEETs consist of both the unemployed—those without work but actively looking for work—and inactive youth outside the labour force, both groups of who also do not engage in any educational or training activity. Because they are neither improving their future employability through investment in skills, nor gaining experience through employment, the risks of both labour market and social exclusion is particularly high.

In this context, it is important to identify the root causes and determinants of falling into NEET status and into different NEET subgroups (Box 1), so that tailored policies can be devised to ensure the productive engagement of young persons in the economy. This study examined the NEET population in Sri Lanka and identified potential risk factors of falling into NEET status. Binomial and multinomial logistic regression models were estimated using data from the 2016 Labour Force Survey conducted by the Department of Census and Statistics.

Key findings

Sri Lanka’s NEET rate—defined as the share of NEETs from the total youth population aged between 15 and 24 years—stood at 26.1% in 2016, slightly above the global average of 21.8%. The female NEET rate, at 34.5%, is over double the male NEET rate of 17%.

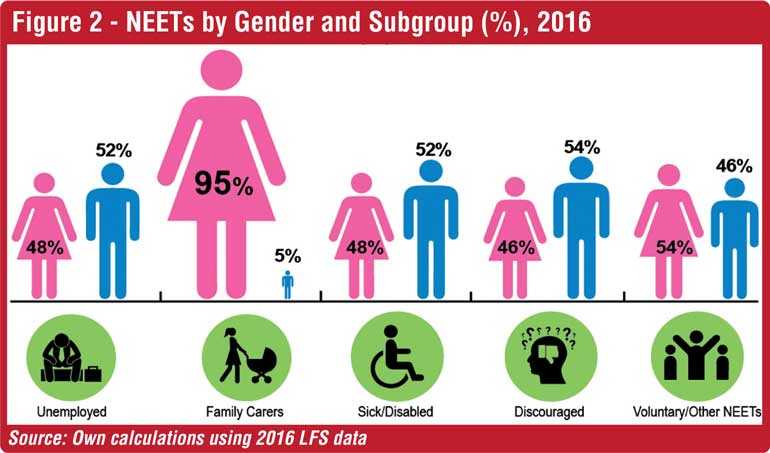

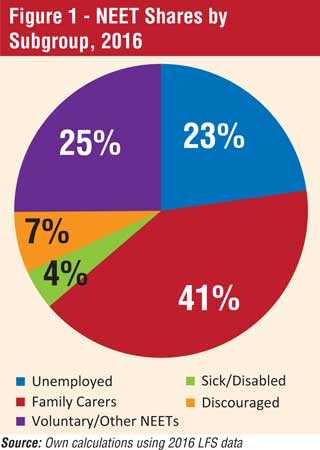

Over 40% of NEETs are family carers, while the next largest shares are of the voluntary or other NEETs and the unemployed (Figure 1). It is this relatively large share of NEET family carers that contributes to disproportionately high female NEET rates, since carers are predominantly females (Figure 2). Available data suggests that most young female carers are engaged in caring for children, with over 70% of the female NEET carer population being married, and over 70% of married female NEET carers living in a household with least one child below the age of five.

Apart from gender, other key risk factors of falling into NEET include: being of ethnic and religious minorities, belonging to the older 20-24 age group, having very low or very high levels of education, being illiterate in English, belonging to a low-income household or one headed by a male, having young children, living in more remote areas, and belonging to areas with relatively low youth unemployment rates.

In terms of NEET subgroups, falling into NEET due to unemployment is more common among the highly educated, particularly males. Factors such as being female, having children under the age of five years, being married, and belonging to ethnic and religious minorities increase the likelihood of becoming a family caring or voluntary/other NEET. Location is the most important determinant of becoming a discouraged NEET.

Policy implications

With regard to female family carers, who account for the largest share of NEETs and face relatively higher risks of becoming NEET, it is important to explore policy options that can release women from household responsibilities and bring them into the labour market. Given that small children are a key risk factor keeping women at home, the provision of good quality and affordable childcare options is an essential area requiring policy attention. These centres would ideally provide free, quality childcare, as well as free transportation to and from the facility, and free on-site basic medical services to both its employees and their children.

Preventing Sri Lankan youth from becoming unemployed NEETs calls for a particular focus on highly educated youth. To provide youth with employable skills and prepare them before actual labour market entrance, several OECD countries have experimented with quality vocational education, apprenticeships, internships, and mentoring programs, which can also be initiated in the Sri Lankan context. Additionally, there is a need for government-led career guidance initiatives, established at the school-level, targeted at advising and directing youth to available education, training, and job opportunities. Improving the quality of education to make it more market relevant is also key.

Given that being a discouraged NEET is largely tied to locational disadvantages, measures need to focus on bringing back hope to potential workers who have given up their job search due to living in conflict-affected and remote areas, with limited access to information and infrastructure. In the EU, financial and mobility assistance is provided to disadvantaged youth, comprising of both support for specific costs—such as transport or accommodation costs—or a grant or allowance, intended to cover the cost of living while participating in learning opportunities, which can be experimented in the Sri Lankan context too. Ongoing efforts to improve connectivity between urban and remote areas are also important.

*‘Sri Lanka’s NEETs: An Analysis of Youth not in Education, Employment or Training’, by Ashani Abayasekara and Neluka Gunasekara, can be purchased from the Publications Unit of the IPS, located at 100/20, Independence Avenue, Colombo 7, and leading bookstores island-wide. For more information, contact the Publications Officer (Amesh) on 0112143107/0112143100 or email [email protected].