Friday Feb 27, 2026

Friday Feb 27, 2026

Tuesday, 10 December 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

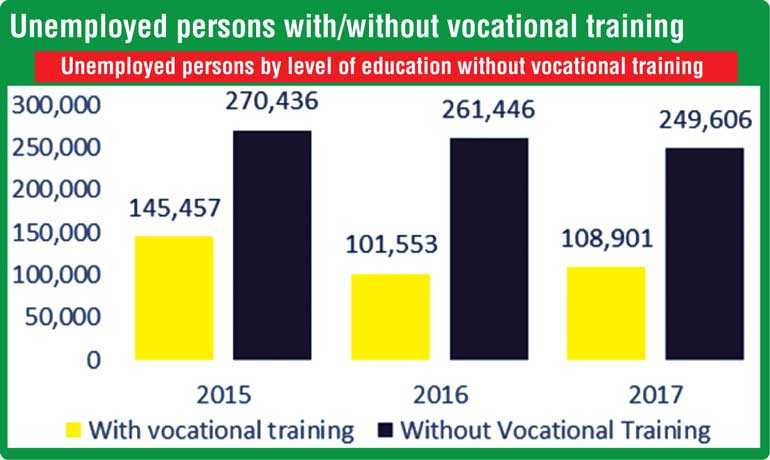

Considering the 15-24 age group, youth unemployment is a well-known obstacle in Sri Lanka with a rate of 18.5% in 2017 exceeding the global rate of 13%. The youth unemployment rate is four times higher than the overall unemployment rate, and 50% of the total unemployment in Sri Lanka is in the youth category (Sri Lanka Labour Force Survey Annual Report 2017). Thus, youth is seen to be a particularly vulnerable age group.

|

GIZ Head of Project Karsten Feuerriegel |

|

EY Partner and Head of Advisory

|

World over, 75% of Generation-X workforce will be replaced by millennials in 2025 – Millennials are the largest segment of the workforce and will continue to dominate in the coming years, as forecasted by the Forbes magazine. Technology trends and disruptive business environments continue to influence businesses to push beyond boundaries for sustenance. This has led to an increased demand for skilled labour, with focus on specialised technical and soft skills to help create the right ecosystems to facilitate business transformation.

Skills gaps, mismatches in labour supply and demand and low female labour force participation are impediments that limits Sri Lanka harnessing the full potential of the country’s youth segment. The shortage of skilled labour in select industries despite the high youth unemployment rate indicates the need for urgent remedial actions (Central Bank Annual Report 2018).

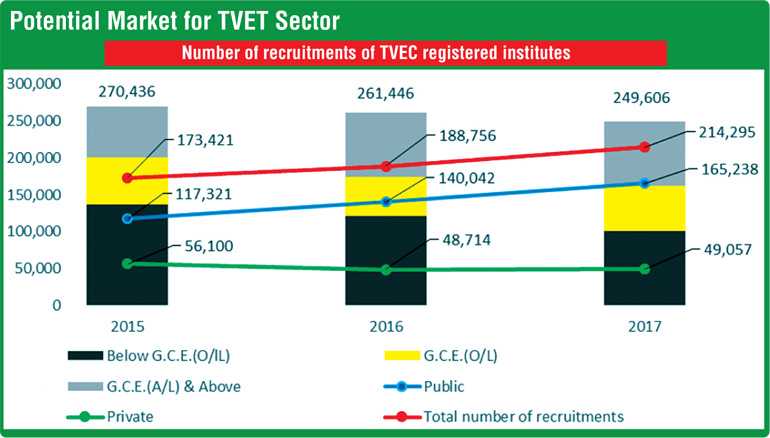

The Vision 2025 of the country, where the aim is to foster growth through a “knowledge-based economy” denotes upskilling our youth is crucial. Thus deliberate efforts must be made by both regulators and training centres towards the development of the TVET Sector, a key segment involved in the professional development of youth.

Despite many initiatives by the Government to develop Sri Lanka’s TVET sector through programmes such as the Skills Sector Development Programme, the sector is yet to reach its potential.

The highest proportion of youth unemployment in the youth population is shown among youth who have completed GCE A-Levels ( 13.7% in 2017) while the NEET (Not in Employment, Education or Training) rate of this group stood at 27.3% in 2017.

EY Sri Lanka Country Managing Partner Ruwan Fernando stated: “There is scope to raise public awareness of the TVET sector and attract more youth into this segment.”

He continued: “The TVET sector can target youth who have just completed their A-Levels as well as youth who are in the NEET category by means of offering OJT and apprenticeship opportunities.”

Many private and public sector institutions collectively construct the vocational sector in Sri Lanka. The Ministry of Skills Development and Vocational Training (MSDVT), the apex body in the vocational sector, has several institutes under its purview, including the Tertiary and Vocational Education  Commission (TVEC), National Apprentice and Industrial Training Authority (NAITA), the Vocational Training Authority (VTASL), Ceylon German Technical Training Institute (CGTTI) and the Department of Technical Education and Training (DTET). Apart from this, there are at least 257 and 197 registered public and private training centres respectively (Skills Sector Development Program Progress Report 2017).

Commission (TVEC), National Apprentice and Industrial Training Authority (NAITA), the Vocational Training Authority (VTASL), Ceylon German Technical Training Institute (CGTTI) and the Department of Technical Education and Training (DTET). Apart from this, there are at least 257 and 197 registered public and private training centres respectively (Skills Sector Development Program Progress Report 2017).

Related organisations also include youth services such as career guidance centres. Yet the question remains whether or not the syllabi of the training centres and the structures of the TVET sector facilitate the upskilling of talent to meet today’s agile business environments.

Lack of governance structures

It is apparent that, despite all the available regulations, mandates, policies and frameworks in place, the responsible authorities find it difficult to carry out the assigned work efficiently and effectively, impeding the progress of the vocational training sector. Some Government vocational training institutes compete to achieve their institutional targets at the expense of nurturing and developing the entire system of vocational training.

To achieve consistency and high-quality training and education it is paramount to instil a well-defined governance structure for the VET sector. In leading countries, the clear regulatory frameworks have facilitated sound awareness of roles and responsibilities amongst relevant stakeholders.

For example, Austria has several key regulatory bodies that cater to the enterprise-training component (represents training providers) and the VET part-time school component (represents VET providers). Although the enterprise training and VET schooling component have distinctive unique roles, the regulations, regulatory bodies, mandates and policies facilitate each stakeholder to work in tandem at all levels (i.e. federal, provincial and local) ensuring VET providers and training providers work hand-in-hand.

In the article titled ‘The skilled crafts sector in Germany’ by Daily FT Deputy Editor Marianne David published in Daily FT following her expedition to Germany to study its Dual Vocational system, Dr. Hendrik Voß, Head of the Department of VET of German Confederation of Skilled Crafts (ZDH), is quoted: “The law determines which professions are skilled crafts and ensures compulsory membership of enterprises in chambers of skilled crafts. The professions carrying out small-scale, individual production and maintenance (mostly local SMEs) represents the total skilled crafts sector in the country, and the dual vocational system ensures the supply of skilled staff via the skilled crafts sector.”

The Ceylon Chamber of Commerce (CCC) in its recently released ‘Sri Lanka Economic Acceleration Framework 2020-25’ document talking about the requirement to develop technical and vocational higher education institutes to expand their reach and to target industry needs emphasise the requirement to promote strong collaborations between NAITA, DTET, TVEC and employer bodies to expand apprenticeship based training as well as to provide a training allowance to apprentices to help stimulate the attraction towards the VET sector.

Fernando, making his comments stated: “Regulators and policy setters must recognise the need to bridge the gaps in the regulation framework whilst updating policies and the TVE act to align Sri Lanka’s TVET sector with best practices in other countries.”

Appropriate amendments to the TVE act should be brought in to ensure consistent coordination and alignment of common goals for Government institutions in this sector. It must facilitate a seamless integration along with the private sector which can help develop a cohesive TVET landscape in Sri Lanka.

Quality of training instructors

EY’s study revealed some OJT providers in Sri Lanka believes that the training provided by training centres does not provide up-to-date technical and soft skills for trainees to carry out job-specific tasks. There is a lack of professional development initiatives to build knowledge of instructors on technological advancements occurring in today’s business environment.

In EU countries, instructors in training institutes are expected to have a bachelor’s or vocational qualification supplemented by pedagogical training and industry experience. Furthermore, in Germany, there are two types of vocational teachers employed; where one segment of teachers studying at universities to become a vocational teacher are required to take a State examination and teach vocational and general subjects.

Others are considered teachers for Vocational Practice (e.g. master craftsman or state-certified technicians) and are required to undergo an additional specific pedagogic training over one-two years. “Alternative recruitment” of graduate engineers into targeted in-service teacher training programmes is also a common practice across federal states (www.apprenticeship-toolbox.eu).

Quality of OJT

Lack of standards imposed on OJT providers is a looming concern specifically affecting the quality of OJT in the TVET sector. Its key limitations include:

These issues have evidently contributed to the high drop out rates of OJT trainees resulting in students only receiving up to the NVQ level 3 qualification, where they do not complete their On-the-Job Training and are thus unable to progress through to the higher NVQ levels.

In Germany, a company is accredited as a suitable training facility upon meeting set criteria. This enables trainees to acquire skills and knowledge deemed necessary to complete the certification programme, thus ensuring the quality of OJTs and the entire framework within the TVET.

In Switzerland, companies are required to apply for VET accreditation where various operational and staff requirements have to be met. A suitable workplace environment with adequate infrastructure and the provision of training which is aligned with course requirements are some of the key operational requirements to be met by OJT providers. VET inspectors (from cantonal VET offices) visit the company to assess staff requirements and determine if the apprenticeship trainers are qualified to provide training for trainees.

Establishing a selection criteria for OJT providers will be of value to ensure quality within the TVET framework. EY Sri Lanka Partner Advisory Arjuna Herath commented: “It is ideal to develop a policy comprising of criteria to be fulfilled by companies to be selected as OJT providers. This will ensure that standards are maintained and training is aligned with course curriculum.”

EY in its study outlines the below criteria as a starting point.

Lack of training regulation causes an imminent adverse effect on the quality of OJT placements

The quality of training provided by OJT providers has sometimes been found to be poor and non-consistent, contributing to the still prevailing skill gaps amongst youth in our country. According to Verite’s Youth Labour Market Assessment Report (2018), the lack of applicants with job-specific technical skills is one of the major challenges faced by employers during the recruitment stage.

The study conducted by EY revealed that although trainees may undergo relevant institutional training at their training institute, it is apparent that trainees would carry out activities unrelated to their course curriculum during their OJT placement despite training institutes providing a Competency-Based Record book which indicates the required tasks to be fulfilled by trainees during the placement. It is further comprehended that there is a lack of awareness amongst OJT providers regarding such documentation resulting in trainees being assigned to tasks misaligned to curriculum contributing to the high drop out rate of trainees during OJT placements. According to the EY study, 56% of OJT providers and 60% of training institutes provide no legal OJT agreement or Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) in relation to the training of trainees.

Dr. Karsten Feuerriegel, GIZ’s Head of project Vocational Training in Sri Lanka (VTSL) commented: “As a best practice, referring to the set framework in Germany, employers are obligated to provide training in a specified manner, following a curriculum and timetable. It is further required for a contract to be written up between the OJT trainee and employer. All OJT providers thus provide training which matches occupational and competency requirements whilst ensuring there is no exploitation of trainees. To avoid loopholes, it is obligatory for the contract to be drawn up before the start of the OJT placement specifying the training curriculum, training duration, allowances, etc. The contract has to then be verified by the relevant industry chamber.”

There is thus an opportunity to introduce mandatory training agreements to ensure that trainees undergo training which is aligned to their course curriculum. Having formal contracts that are then verified by the relevant body e.g. TVEC, should be a precondition to OJT placements in Sri Lanka. To increase convenience for companies, sample or standardised forms for training contracts can be readily made available online by the relevant regulatory body.

Inconsistencies in training inspections: Need for manpower and backing of regulation

Although training inspections are a compulsory component of OJT, EY’s study revealed many inspectors do not visit OJT providers due to the insufficient manpower. The lack of recognised criteria to assess training organisations has also resulted in ineffective monitoring thus leading to limitations such as deviations from syllabi, inadequate facilities, and exposure for trainees.

Referring to the practice adopted in Switzerland, the inspectors are required by law to inspect OJT providers. In Cantons (States) it is required for inspectors to regularly visit the companies, where if they do not meet the set standards, the company’s VET accreditation would get revoked.

Concerns over the popularity of TVET amongst its stakeholders

Youth is considered a key target market of the TVET sector. However, a study conducted by Verite (Youth Labour Market Assessment Sri Lanka 2018) showed that out of 80% of unemployed youth surveyed, 33% selected vocational training as the preferred skill acquisition. Yet, only 13% of respondents had completed any form of vocational training.

The low participation may be attributed to the lack of awareness and resultant lack of interest of TVET amongst youth which is supported by our findings. As per the finding of EY KIIs, the key constraint of youth is ‘unawareness of the courses available’. This has led to unsuitable course selections and high drop-outs.

One of the training centres commented: “From a group of students who register for the hospitality sector NVQ course, only one or two have the true skills and passion to perceive a career in the hospitality industry.”

Due to the lack of perceived choice, youth may settle with choosing a popular or trending course and as a result, lack the necessary skills and passion to complete the course successfully.

There is a lack of awareness amongst youth regarding the relevance and value of NVQ. Information is not knowledge. It is therefore important to raise the awareness and attractiveness of Sri Lanka’s TVET sector, especially in terms of the courses available and career opportunities from following NVQ.

Considering the cultural norms in Sri Lanka, youth are generally unwilling to travel far from home unless they are provided with safe transportation. Considering the majority of the target population within each industry, and their livelihood, ensuring trainees have access to company transport (if there is) or providing a travel allowance can encourage trainees to undertake OJT placements and receive NVQ qualifications.

Potential OJT providers must assimilate to support the TVET ecosystem

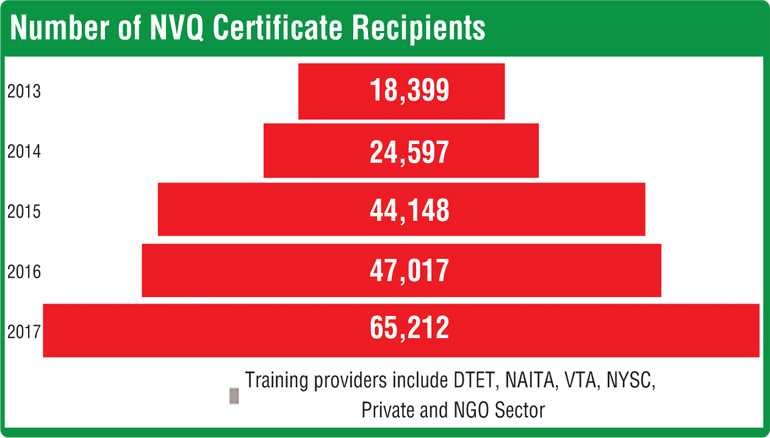

The National Vocational Qualification (NVQ) framework, a seven-level system, was introduced in 2004, to meet local and global professional standards. To ensure that NVQ holders meet the requirements of the job market, to reach NVQ level four, it is compulsory for students to do OJT, enabling them to gain a first-hand insight into the workplace.

EY’s survey illustrated that 67% of OJT providers do not have thorough knowledge of National Competency Standards (NCS) or NVQ. As a result, there is a shortage of OJT placements available. In addition, in Sri Lanka, since it is possible to perform tasks in trades eg: construction and repairs without an NVQ qualification, companies may disregard the NVQ certification during the recruitment process.

It is clear that greater awareness needs to be created on the quality of NVQ registered students. Interviews conducted by EY exemplifies the difficulty in convincing and engaging new companies, including large-scale firms, as OJT providers. This is due to the lack of awareness of NVQ and NCS in the corporate sector.

In Germany, there is acceptance and recognition of students in vocational training as having in-demand and high-quality skills. Cooperation between key stakeholders including the private sector, Government, and labour unions have contributed to the success of the VET system.

Germany also brought in an amendment to the Vocational Training Act in 2005 to introduce an alliance between the Federal Government, Federal states, and companies. Companies play a key role in updating and introducing training regulations and occupational profiles. Cooperation with the Government ensures that public sector training centres provide their students with up-to-date skills.

Moreover, the system has intrigued a sense of social responsibility amongst employers to help support the youth through participation in OJT. Businesses who participate as OJT providers believe that vocational training is the best form of recruitment as employers save almost no recruitment costs and avoid the risk of hiring talent from new and unfamiliar environments.

OJT providers are a vital element within the TVET framework. Thus, buy-in from employers is crucial. Herath commenting stated: “Raising awareness amongst the corporates on the NVQ and NCS should be prioritised and relevant associations must gain industry buy-in to strengthen the TVET ecosystem.”

Progression opportunities and permeability

“As Sri Lanka’s TVET system has a negative stigma, where parents and students believe higher education (GAE) is more prestigious as opposed to VET, it is essential to create transferability between these two pathways where students can acquire skills from both pathways building a highly-skilled workforce,” stated Herath.

CCC in its report ‘Sri Lanka Economic Acceleration Framework 2020-25’ recommends providing seamless progression pathways from secondary education to technical and vocational education for those who do not enter universities. It also recommends expansion and strengthening of the newly-introduced vocational stream in secondary education.

A key factor that could influence the attractiveness of vocational systems is its permeability with other pathways and progression opportunities. In the EU countries, as there is a growing trend towards GAE, improving the parity between the two systems has become a focus.

In Germany, if graduates of the VET system have several years of work experience in their occupation, the system allows them to access related courses at higher education institutes. Further, Germany’s dual training is divided into initial VET and Continued VET (CVET, access to specialist knowledge). CVET graduates and their certificates of trade and technical schools are accepted as university entrance qualifications.

Initiatives e.g. ANKOM initiative (transferring vocationally acquired competencies to higher education programs) (Federal Institute for Vocational Education and Training – BIBB), joint curriculum development are still being carried out to further improve permeability.

David states in her article on ‘Dual Vocational Education and Training in Germany (VET) – Part I: The beauty of the German dual education system’: “The dual training had enabled employees to face changes in today’s agile working environment and relaxes labour relations concerns resulting from workers changing employers and moving into other professions more frequently. This ascertains that the broad-based, non-specialist initial vocational training is the foundation for successful integration into society and the working world.”

Singapore’s secondary education system is also known for being extremely flexible where there are multiple paths which allow students to transfer between vocational training and GAE at any time, at both secondary and post-secondary levels e.g. With Singapore’s WSQ system, graduates can get admission into polytechnic part-time diplomas or institutes of higher learning programmes. They can further get credit exemptions at education institutes.

Financial constraints within the TVET sector

Financial constraints have impeded the progress of Sri Lanka’s vocational sector where insufficient funding has limited investments in training of staff, inspectors and training material including tools and equipment which is crucial for the training of students.

Funding of Sri Lanka’s vocational schools are still primarily supply-driven, leading to inefficient resource allocation and lost opportunities. In order to develop training institutes which provide demand-driven and high-quality courses, countries are converging to modern financing models such as co-financing where contributions to the vocational system come from both the Government and employers and sometimes trainees.

In Germany, not only do companies see apprenticeship training as an investment for skilled labour, they also consider it their social duty. As a result, a competitive allowance is paid for an apprentice. The companies also voluntarily contribute to related costs e.g. additional training costs, aptitude tests for in-company trainers, etc. Since roughly 67% of the costs incurred by employers are offset by the productive output of trainees, private investment will always be sustained. To be able to follow Germany’s model implies that significant efforts will be needed to first gain the industry buy-in.

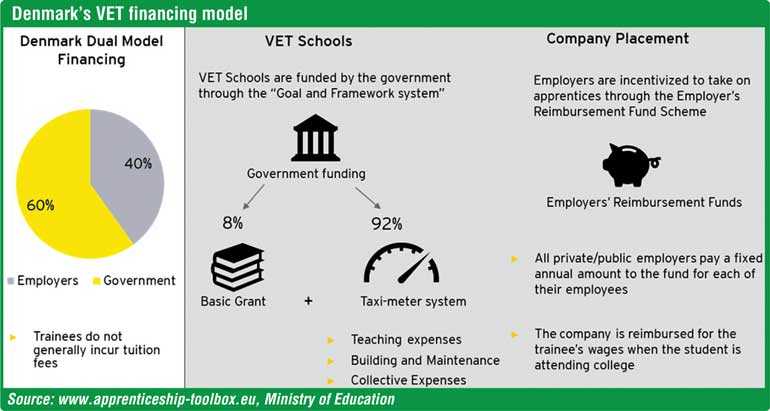

Denmark’s financial model is also well recognised and ensures the delivery of high-quality in-demand courses through its performance-based funding system. While the Government provides a basic grant to institutes, additional funding is given based on the outcomes achieved. This result-oriented ‘taxi-metre’ model directly links funds to institute performance incentivising institutes to improve on quality and efficiency of education. Meanwhile, its Employer Reimbursement Fund compensates companies for the training costs incurred encouraging firm participation in conducting On-the-Job Training.

Introducing performance-based funding in Sri Lanka can help eliminate the key issues the vocational institutes face, including the lack of efficiency and the mismatch of supply and demand for vocational courses. Using measures such as Denmark’s Reimbursement Fund can attract companies to participate as OJT providers.

Conclusion

EU countries including Germany, Austria and Switzerland, are seen as leading examples where their strong vocational sectors have helped contribute to low youth unemployment rates and the development of a highly-skilled workforce. Benchmarking against countries with some of the best vocational sectors whilst evaluating the applicability and adaptability to the Sri Lankan context can pave the way towards the development of our TVET sector to effectively contribute to building a better working world.

Although Sri Lanka follows vocational systems which are similar to those in leading countries, it is evident that several issues have stagnated the growth and efficiency of this sector. Introducing strong governance structures with regulations to maintain the quality of the training institutes and OJT providers will strengthen the TVET sector. Performance-based funding for training institutes and co-financing methods where all stakeholders contribute towards the specialised technical training will help facilitate funding for this sector, especially in the context where budgetary finances are limited.

Moreover, raising awareness of the opportunities for the youth and NVQ course standards amongst employers will facilitate the sector’s future growth and sustainability. Although through the SSDP major reforms in the TVET sector are taking place e.g. Performance-based funding and training of staff being introduced in selected training institutes, progress has been noted as unsatisfactory (SSDP Progress Report 2017).

[This article is based on a recent study conducted by Ernst & Young (EY) in relation to ‘On the Job Training (OJT) placements in the TVET sector in Sri Lanka’ for Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) which surface some of the critical constraints within Sri Lanka’s TVET sector. The findings are based on surveys, key informant interviews and focus group discussions covering a sample of Government institutions, GIZ VTN partnered training centres, OJT providers and trainees placed in OJT. We recognise the contribution by the Daily FT, which participated in a programme on Dual Vocational Education and Training in Germany at the invitation of the Federal Foreign Office in March this year; Daily FT Deputy Editor Marianne David for sharing her experience in her expedition to Germany and the information she provided from German agencies.]