Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Saturday, 6 June 2020 00:08 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

A tribal family in Indonesia

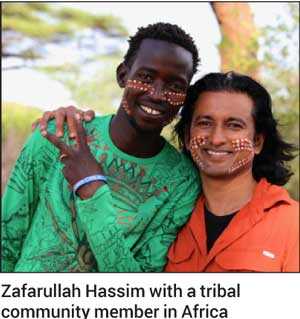

The Harmony page this week features an interview with Zafarullah Hassim, a Sri Lankan based in remote locations of the world, working with indigenous communities, as a peacebuilder and community-based communications specialist. He shares his views based on his experiences and calls for the promoting of a harmonious and inclusive world order. Following are excerpts:

Q: You are a Sri Lankan who has for over two decades lived (and still based) outside Sri Lanka working in remote parts of the world as a peacebuilder, film maker and as a communication specialist. Could you describe your work?

A: I have worked for the past 20 years in over 10 conflict-laden countries in Asia, Africa and Eastern Europe. My role has been as a field worker interacting directly with grassroot communities and with policy makers and I have been engaged in peacemaking and peacebuilding efforts as well as delivering peace dividends and community stabilisation efforts.

As a communication specialist focused on peacebuilding, it is my firm conviction that any conflict within a family, society or between states or other social groups emanates from a perspective of information – the absence of information, prevailing partial information or the presence of distorted information. And, correspondingly the resolution is to bridge the information gap through an unbiased context analysis and meticulous conflict mapping exercise. Indigenous societies used these methods long before we started to use them in contemporary context.

My intention has always been on how to extract the deeper values and ethics embedded in their traditional wisdom of a seemingly simple system of governance and restructure it into a meaningful way that would have greater impact on their current lifestyle. The more creative and realistic we can get in webbing a resolution the more successful steps we could take for eliminating the information gap that paves the way for new relationships between conflicting individuals and parties.

The larger organisations and the smaller community organisations have a very intrinsically linked position in creating social change. Their functions and goals are very complementary and organically necessary. The problem is with the people who serve in those positions – the purity of their motives, the standards of their operations, the true love and respect that they do their services with…that’s what makes the difference

The challenge is not to be prescriptive but rather to present with humility and wisdom alternative perspectives that they may have forgotten or were unaware of in the past, multiple options that they perceived not to have at their disposal or provide different interpretations that they had not thus far comprehended. This leads to a possible change of mindset that thrusts the parties to conflict to seek their own unique resolution. I utilise techniques of applied theatre in personal and interpersonal relationship building and conflict sensitive media approaches for the masses.

The challenge is not to be prescriptive but rather to present with humility and wisdom alternative perspectives that they may have forgotten or were unaware of in the past, multiple options that they perceived not to have at their disposal or provide different interpretations that they had not thus far comprehended. This leads to a possible change of mindset that thrusts the parties to conflict to seek their own unique resolution. I utilise techniques of applied theatre in personal and interpersonal relationship building and conflict sensitive media approaches for the masses.

Q: Could you speak about your experiences working in Africa among the many diverse African tribes?

A: I spent four years working in central Africa based in Uganda. The bulk of my time was spent in Northeast Uganda bordering with South Sudan and Kenya – Karamojong Region consisting Karamojong, Jie, Tepeth, Kadama, Ik, Dodoth, Pokot, Labwor, Mening and Nyangia tribes. Our team was assisting the people with self-reliance and self-sustainability leading to community stabilisation of this region.

I was focusing on utilising theatre and media techniques via TV broadcasts and live community screenings throughout the region showcasing how diverse ethnic groups were slowly changing their lives from aid dependency to self-sustainability. The objective was to involve in all theatre and visual productions as many local members, governmental officials and informal leaders of each community as possible, thus reflecting their unique organisational abilities and creative capacities.

While using theatre and video tools to educate the tribal population on utilising local resources for crop management and animal rearing towards having a balanced diet and income generation, I had to focus on running programs demystifying these tribes and humanising them since they were treated as less than humans by the rest of the ‘modernised’ population of the country.

In a region rich with natural resources, a Karamojong tribal family’s monthly income was about $ 15 ten years ago. I do not think much has changed. I spent a little over a year in Acholi land in Northern Uganda working with the Acholi tribes where the Lords Resistant Army (LRA) during a 30-year period had abducted over 67,000 youth, including 30,000 children recruiting them as child soldiers. Our team was tasked to design and implement an awareness campaign and a strong outreach mechanism on community-based reintegration under the government Amnesty Act, to local government, civil society organisations and communities to identify vulnerable at-risk youth and encourage them to seek suited employment opportunities.

Q: What is the core wisdom you learnt from these tribes, a world view that may be different to what we are taught and influenced by?

A: All of these tribes often cast aside as ‘uncivilised,’ or ‘backward,’ have within them great traditional wisdom. They have survived extreme conditions of life for hundreds of years through their own unique systems of self-governance and communication based on this collective wisdom that valued each member of the tribe as well as respected the natural world they coexisted with.

I personally believe that the traditional wisdom of indigenous groups around the world which were custom tailored for the growth and development of these tribes, should be not only respected but safeguarded and augmented with modern development tools and techniques. But the unfortunate reality witnessed globally is that colonialism and neo-colonialism derailed and nullified all these traditional wisdoms and introduced systems of thought and practice that was beneficial for the colonials. Hence a new generation of confusion was given birth to.

The entire lifestyle of much of the world was cast upside down and once the colonials left the same positions and arrogance was continued by the handful of local people who were no different than the foreign occupiers. The tribal people are still governed and exploited by greed and power based socio-economic systems under the pretext of modernism and development that have no regards for any of the value based traditional systems that upheld respect for humans and the environment. The tribal people in Karamoja and Acholi for example had laws against killing animals, chopping down trees.

A traditional community leader and a healer of Mentawai tribe in Sumatra, Indonesia once told me that he preferred the older tribal system of education where the community as a whole were caretakers of their people. If a young man took something with no permission the leaders would be very sad. They would invite the community and tell them that all the young man needs to do is to state his need and the community’s duty was to provide. Then he went on to explain how today, people get an education is schools and universities and then cheat on the local population and steal from them – corruption. Then the police would take them someday to the courts and he may get out or spend some time in the prison. Then he comes out and steals again. ‘What is the purpose of such education’ was his question.

While working in Africa, a high ranking local tribal leader once asked us “Why are foreign people and organisations so worried and interested about human rights? Because once the funding ends nobody cares after that.” That is a very true statement that applies to situations all around the globe.

There are also good things that developing countries in the east could learn from the developed west and vice-versa. Most of the time the humility and the simple yet harmonious lifestyle of social groups such as indigenous communities are interpreted as weak and backwards. Yet never have the lifestyles of these simple social groups ever threatened the environment or damaged the earth’s stratosphere. It was the greed and power based political systems that led to industrial and agricultural revolution that created the current status of imbalance and once things are beyond control then we have to defer back to those very traditional wisdoms upheld by indigenous people.

Q: You have worked as a peace-builder for several international agencies... You also have worked quite a lot on your own outside the influences of these agencies... Could you speak of the difference based on your experiences?

A: Working with and without these international agencies both have its pros and cons. Larger international organisations, got the needed resources and the power for greater and swift changes. Working in smaller groups and organisations, has given me the benefit of freedom from bureaucracy as well as more personal and interpersonal communication approaches which are easily manageable and much more of a hands-on approach for social changes. The goal here for me is to create a space and motivate a small group of people to develop their own model of change, setting up practical examples of principles in action, based on their own socio-cultural contexts and often their own heritage knowledge.

During my two-year period of work at the Rohingya camps in Cox’s Bazar, literally thousands of very powerful State leaders, politicians, the highest-ranking UN officials visited the camps. But to-date nothing has changed in these people’s lives during that that two-year period of ‘aid-tourism.’ The immediate result of the UN Secretary General’s visit led to two things that I witnessed myself, the brutality in which the security sector handled bystanders from Cox Bazar camps to the Kutapalong refugee camps, to give him a field tour and the statement of him saying ‘the situation is very complex.’

The larger organisations and the smaller community organisations have a very intrinsically linked position in creating social change. Their functions and goals are very complementary and organically necessary. The problem is with the people who serve in those positions – the purity of their motives, the standards of their operations, the true love and respect that they do their services with…that’s what makes the difference. It has nothing to do with the organisation of how big or small or if it is western of eastern. Everybody talks about religion and rights and justice and equality. If one possesses a religion or not is not the key factor but the practice of a principle. Just the daily practice of one principle of honesty or truthfulness.

A traditional community leader and a healer of Mentawai tribe in Sumatra, Indonesia once told me that he preferred the older tribal system of education where the community as a whole were caretakers of their people. If a young man took something with no permission the leaders would be very sad. They would invite the community and tell them that all the young man needs to do is to state his need and the community’s duty was to provide. Then he went on to explain how today, people get an education is schools and universities and then cheat on the local population and steal from them – corruption. Then the police would take them someday to the courts and he may get out or spend some time in the prison. Then he comes out and steals again. ‘What is the purpose of such education’ was his question

I spent some time working in the eastern and north-western parts of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). By this time the operational cost of the UN in DRC alone per day was about $ 1.25 million. But the life conditions and socioeconomic systems of Eastern DRC in the Goma region was absolutely same as 40 years before when the father of a friend of mine from the Malaysian military was working with the UN peace keeping forces in Goma. So, one wonders what happens to all this money for peacekeeping while that country has never seen peace in the recent history. With $ 1 million Africa one can build an entire village with well-equipped facilities of health and education, which adds up to 365 villages, if begun within a year.

In my career, I have worked with a few large organisations. If we can stand on solid principles and speak for the voiceless, there is always the chance of getting some truly meaningful work done. After I left those organisations, I never lost direction in continuing my services as un unpaid volunteer as well as being affiliated with small local organisations. I have learnt much from the indigenous people that I encountered and one aspect is how to be truly happy with little resources as possible. This has given me the opportunity to travel and live and work with some of the poorest populations. I have met likeminded individuals on these journeys from the east and the west and our sharing of experiences and learning from each other provided much strength and motivation.

Q: In this world, only a few have official roles as peacebuilders. However, would you say that every human being is and should be a peacebuilder in his or her everyday life?

A: Yes. This is so. But most forget it.

The current civil unrest prevailing in the US due to racism and the chaos created worldwide by COVID-19 are yet more proof of the failure of elitist rule of arrogance, might and money and dysfunction of hypocritical systems. All of these occurrences bring us back to the simple wisdom harboured within tribal and indigenous societies, the wisdom of humility and simplicity and respect to every living thing around them – the concept of finding peace within one’s self. It is only if this wisdom was applied in a global scale that would bring true harmony to the planet.

All of today’s international discussions are but ways developed to create jobs and get paid more for talking than action. The words of these well-groomed hypocrites are more valued by the media and contemporary society than the simple deeds of simple people because they did not attend glamourous universities, they do not have fancy certificates and they do not have a decent dress. What everyone forgets is that these very learned and sophisticated people with money and power are the very ones who have forced the world into the current condition of conflict and chaos.