Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday, 9 December 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Aysha Maryam Cassim

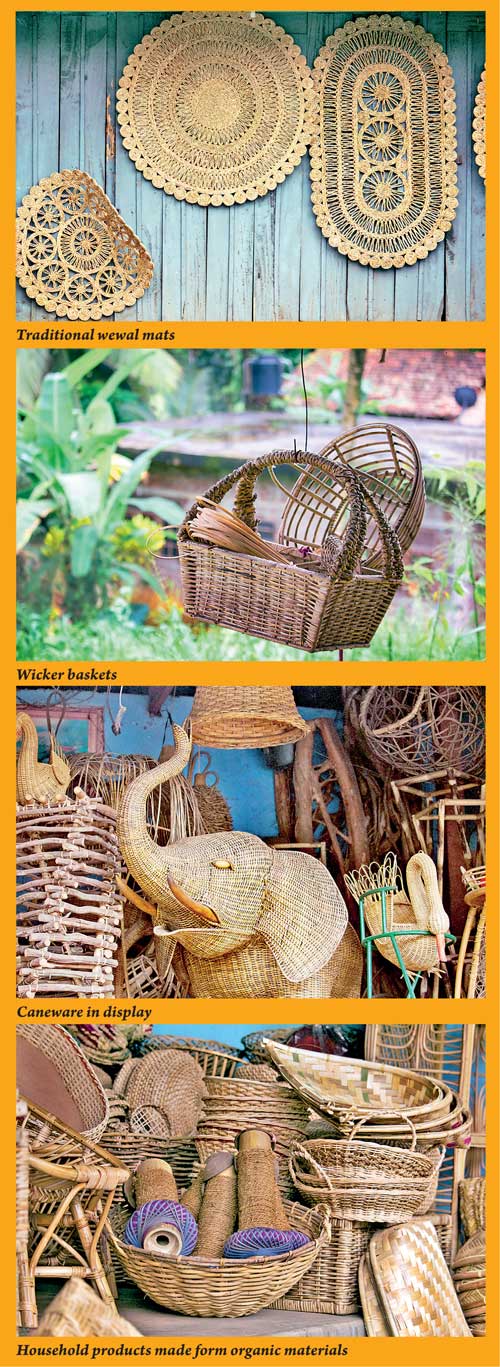

The Colombo-Kandy A6 is the road most travelled by me. As a child, I recall my parents pulling over by the wewal boutiques in Radawadunna located next to Kaju Gama. From chairs to brooms and fancy string-hopper moulds, these shops sell a variety of artisan products made from organic materials. For foreigners who frequent this route, these craft village is a street spectacle worthy of being captured in photographs.

K.P.S Karunanayake, JoP, has been in the cane crafts industry for 20 years. He was designing wicker hamper boxes for the season and told us that he often gets orders from wedding planners. From producing hand-woven pouches to mini wedding cake casings, his client base has rapidly expanded towards a thriving market.

A native of Radawadunna, he told us an interesting story of how the word Radawadunna came into use. Apparently, it is a simplified version of Sinhala phrase “Rajaa Wada Unna” – the place where the King landed.

A sense of nostalgia

The rattan-cane or stick which is known as wewala in Sinhala was used in households to intimidate children. Although it is a rarity to see one of those in modern households and schools, surprisingly the infamous wewala is still being sold for Rs.20 today.

Hand-made rattan furniture remains treasured for its nostalgic and sentimental value. Its value lies in the labour and creativity that goes into the making of the design which makes rattan-ware infinitely superior to machine-made plastic equivalents.

Rattan has been gracing Sri Lankan verandas and living rooms for many years. Just like a fresh coat of paint, a new rattan weave can magically transform the armchair in your patio which you inherited from your great-grandfather to look brand new and impeccable.

Today, rattan is no longer a material reserved for beach resorts and getaways. From pendant lights to armchairs, rattan adorns contemporary home interiors and commercial spaces, proving how versatile it can be when it comes to decor.

Although it may seem like there has been a decrease in demand for cane furniture with the availability of fairly reasonable plastic ware, cane is making a comeback. Rattan’s natural aesthetic makes it an ideal complement for minimalistic designs with an organic flair. Pair it up with plants and earthy neutrals for a cohesive style.

The market

The exquisite craftsmanship of Radawadunna artisans brings out the true beauty of rattan. I met with a few artisans in Radawadunna at their atelier on a weekday afternoon. Their dexterity is mind-blowing. Many of them take pride and pleasure in their profession and admit that seeing the finished piece gives them an unparalleled satisfaction.

M.A. Dinesh is taking the traditional rattan craft in Radawadunna to a whole new level. His own business, Cane Wood Furniture, is a store dedicated to manufacturing bespoke cane furniture which includes modern rattan beds, bar stools and sofa-settees.

“There is a range of possibilities in this industry,” he says. Innovation is what we need to advance.

Business is not as good as it was before. Demand for cane-ware is stagnating. “All we get now is repairs,” says Madushanka Kularatne, a young artisan from Samanala Cane Industries.

In order to keep up with the expansion of the market, designers are branching out from their conventional craft and venturing into developing small-scale, less labour-intensive designs including ornamental figures, lifestyle-ware and souvenirs.

New Irangani Musicals specialises in producing percussion instruments. It’s a vibrant little shop that stands out in Radawadunna. K.S.K Pathiranage, the owner of this shop, has been making congas, bongos and traditional cowhide raban for 10 years.

Blood, sweat and art

A fair amount of strength is needed to pull the rattan into shape when it’s being woven. A person with years of experience and nimble fingers could effortlessly plait the rattan to create decorative bands around the frame.

Blood, sweat and creativity are interwoven in the pattern with long strands. Their craft is labour intensive and time-consuming. At present, a “wewal putu wiyanna” (cane weaver) charges around Rs. 2,500 to weave an old chair.

Rattan is a natural, sustainably grown material, which flourishes in the tropics. The word ‘rattan’ which is alternately called wicker comes from the Malay word ‘rotan,’ a specific plant belonging to the palm family.

The rattan cane is usually supplied from Manapitiya in Sri Lanka or Indonesia and Malaysia. A kilogram of imported rattan costs roughly around Rs. 2,000-3,000. It is a very brittle material that should be handled with care. The long, thin, rattan canes are first soaked in water for an hour before weaving. Once it’s dampened, it’s more malleable and easier to work with.

Asoka is a man who must be in his 60s. He is a freelance craftsman who provides his skills for different workshops. He was kind enough to demonstrate how a walking stick is made.

First, the fat cane is heated using a blowtorch for about 20 minutes to make it malleable, then it goes on to a bending machine called achchuwa. After cooling, the cane is bent into the required shape. A skilled artist with experience knows how the material will react.

The future of Radawadunna

The craftsmen you see today could probably be the last surviving generation of rattan weavers. The market for handicrafts is on the verge of demise and only a few are trying their best to innovate and keep up with the growing demands of the industry.

Decades ago, there had been 185 shops on either side of the main road in Radawadunna village. Now, only a few stalls remain and most of the youngsters are surviving on a meagre wage doing labour work and toiling away in garment factories.

There haven’t been any plans by the State to create an apprenticeship scheme so that youngsters can learn the techniques and master their skills from their fellow maestros.

The future of Radawadunna rattan village has to be saved from its lingering death. It’s not just the Government’s responsibility but also the artisans themselves who can genuinely make use of the full potential of this wild vine to suit the tastes of the times.