Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday, 14 July 2018 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By D.C. Ranatunga

Denagena giyoth kataragama – Nodena giyoth ataramaga

The saying that if one knows the right track he will end up at Kataragama – otherwise he will get stranded, has been in our vocabulary from the time we were children. Now as oldies we keep repeating it, not about going to Kataragama but as a common saying when one is not quite sure of the place he wants to go to.

Kataragama is mentioned obviously because it was a tedious journey in the old days. There was no road to approach the place in the deep-south. People had to walk through the jungles to reach Kataragama – well-known as a religious place visited by pilgrims of many faiths, particularly Hindus and Buddhists.

Kataragama was referred to by Sir Ponnamblam Arunachalam as “a lonely hamlet on the south-east coast of Ceylon in the heart of a forest haunted by bears, elephants and more deadly malaria”. An article by him appearing in the Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society in 1924 states that the Ceylon Government thought of Kataragama especially twice a year when arrangements had to be made for pilgrims, and precautions taken against epidemics. Hardly anyone goes there except in connection with the pilgrimage, he writes.

A hundred years earlier, Dr. John Davy, the Army surgeon and physician to Governor Sir Robert and Lady Brownrigg (1817-19), wrote about his trip to Kataragama when, due to the condition of the roads, he was “obliged to send back my horse, the greater part of the journey was performed on foot, or in a chair tied to two poles and carried on men’s shoulders”.

Discussing the significance of Kataragama, Sir Ponnambalam says it was held in high esteem in the third century before Christ, and is one of the 16 places said to have been sanctified by Gautama Buddha. He refers to a bo-sapling from the Sacred Bo-tree from Buddha Gaya being given to the nobles of Kajara-gama, as Kataragama was then called, and is still seen in the dewale premises.

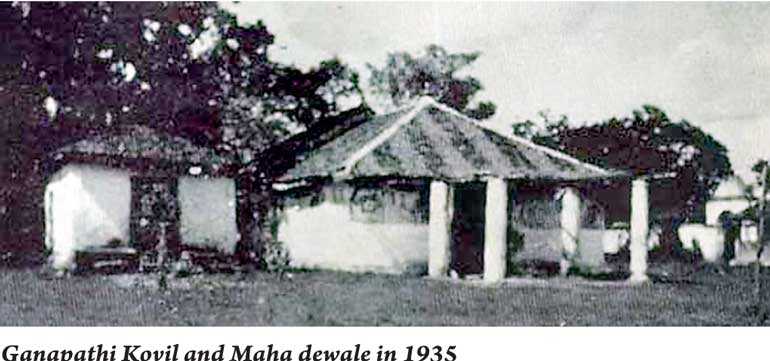

Kiri Vehera in close proximity to the dewale dates back to the reign of King Mahanaga, ruler of Mahgama (present day Tissamaharama).Most Buddhists worship Kiri Vehera prior to proceeding to the dewale.

Buddhists also have great faith in the God of Kataragama.

Sir Ponnambalam describes what Kataragama means to the Hindus thus: “Kataragama is sacred to the God Karttikeya, from whom it was called ‘Karttikeya Grama’ (City of Karttikeya), shortened to ‘Kajara-gama’ and then to ‘Kataragama’.

The Tamils who are the chief worshippers of the shrine, have given the name a Tamil form, ‘Kathirkamam’, a city of divine glory and love, as if from ‘kathir’, glory of light, and ‘kamam’, love (Skt.’kama’), or town or district (from Skt. ‘grama’).

By Sinhalese and Tamils alike the God Karttikeya is called ‘Kandaswami’; by the Sinhalese, also ‘Kanda Kumara’ (“Kanda’ being the Tamil form of Sanskrit ‘Skanda’ and ‘Kumara’ meaning youth), and by the Tamils ‘Kumara Swami’, “the youthful god”. More often the Tamils call him by the pure Tamil name ‘Murukan’, “the tender child”. He is represented in legend, statutory and painting as a beautiful child or youth”.

In ‘An Account of the Interior of Ceylon and of its Inhabitants with Travels in that Island’ (published in 1821), Dr. Davy states: “Kataragam (his spelling) has been a place of considerable celebrity, on account of dewale, which attracted pilgrims not only from every part of Ceylon, but even from remote parts of the continent of India. Aware of its reputation – approaching it through desert country, by a wide sandy road that seems to have been kept bare by the footsteps of its votaries – the expectation is raised in one’s mind, of finding an edifice in magnitude and style somewhat commensurate with its fame; instead of which, everything the eye rests on only serves to give the idea of poverty and decay.”

Kataragama had been an isolated village consisting of a number of small huts mainly occupied by “a detachment of Malays, stationed under the command of a native officer”.

Davy discusses at length the separate dewales in the compound and what can be seen inside the main dewale. “The Kataragam dewale consists of two apartments, of which the outer one only is accessible. Its walls are ornamented with figures of different gods, and with historical paintings executed in the usual style. Its ceiling is mystically painted cloth, and the door of the inner apartment is hid by a similar cloth. On the left of the door there is a small foot-path and basin, in which the officiating priest washes his feet and hands before he enters the sanctium,” he writes.

My last visit to Kataragama would have been over two decades ago and I remember what I saw was not different from what Davy has written. We waited among the crowd with the ‘pooja vattiya’ – offerings of fruits – which was collected by one of the assistants and taken in. Meanwhile, the bells rang nonstop until the ceremony was over.

My last visit to Kataragama would have been over two decades ago and I remember what I saw was not different from what Davy has written. We waited among the crowd with the ‘pooja vattiya’ – offerings of fruits – which was collected by one of the assistants and taken in. Meanwhile, the bells rang nonstop until the ceremony was over.

We did not see what went on inside but waited until the ‘pooja vattiya’ with a few fruits was returned. It was not necessarily what we had given but it did not really matter since the fruits were more or less the same. The devotees tasted the fruits that were returned. They also collected the oil from the ‘pol thel pahan’ which were lit up, into small bottles to be taken back home.

Davy’s observation of the god of Kataragama is that he is not loved, but feared and says that his worship is conducted on that principle. He does not indicate how he came to that conclusion.

“The situation of his temple, and the time fixed for attending it, in the hot, dry, and unwholesome months of June, July and August, were craftily chosen. A merit was made of the hazard and difficulty of the journey through a wilderness, deserted by man, and infested with wild animals, and the fever which prevails at the season was referred to the god, and supposed to be inflicted by him on those who had the misfortune to incur his displeasure,” he writes.

These observations do not apply today. The area is thickly populated, rest-houses and guest houses are aplenty for visitors to reside, business is thriving, roads are well maintained, the journey is just a few hours from any part of the country, and there is no fear of malaria. The pious nature of the visit is, however, maintained and the number of pilgrims keep increasing. Irrespective of festival time, Kataragama draws crowds throughout the year.