Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Saturday, 16 March 2019 00:02 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Dr. Tony Donaldson

Three giants of the Sri Lankan arts world passed away last year. The visual artist Neville Weereratne died in Melbourne on 3 January, aged 86; the filmmaker Lester James Peries died in Colombo on 29 April, aged 99; and the singer Ivor Denis passed away at his home in Seeduwa on 18 June, aged 86.

I knew Neville had passed away, but I only heard about Lester and Ivor by chance during a lunch meeting with Prasanna Gamage, the Consul General of Sri Lanka in Melbourne. The meeting took place on 24 August and it was uncanny that at the very moment he was telling me the news about Lester and Ivor, the then Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull was being toppled by far-right conservatives in the Liberal Party in a disloyal act driven by bullying, betrayal, backstabbing, bitterness and revenge.

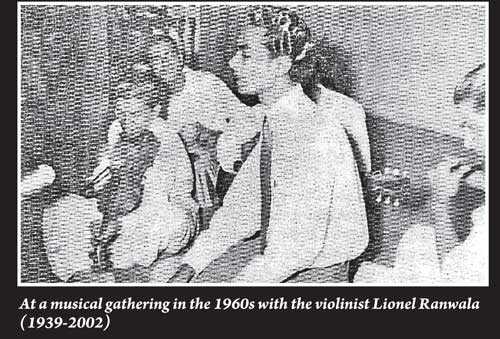

The contrast between the life of Ivor Denis and the madness taking place in Canberra on that Friday afternoon in late August was unmistakeable. Loyalty can be as fickle in the music world as it is in politics as Sunil Santha experienced. But Ivor was different. His strength of character was on a higher level as seen in the unbreakable loyalty to his guru for 66 years, from the day he met Sunil Santha in 1952, till the day he died.

It was a remarkable loyalty, rare in human relationships, and it was not surprising that those paying their final respects to this icon of Sinhala music included artists, musicians, ministers, and President Maithripala Sirisena.

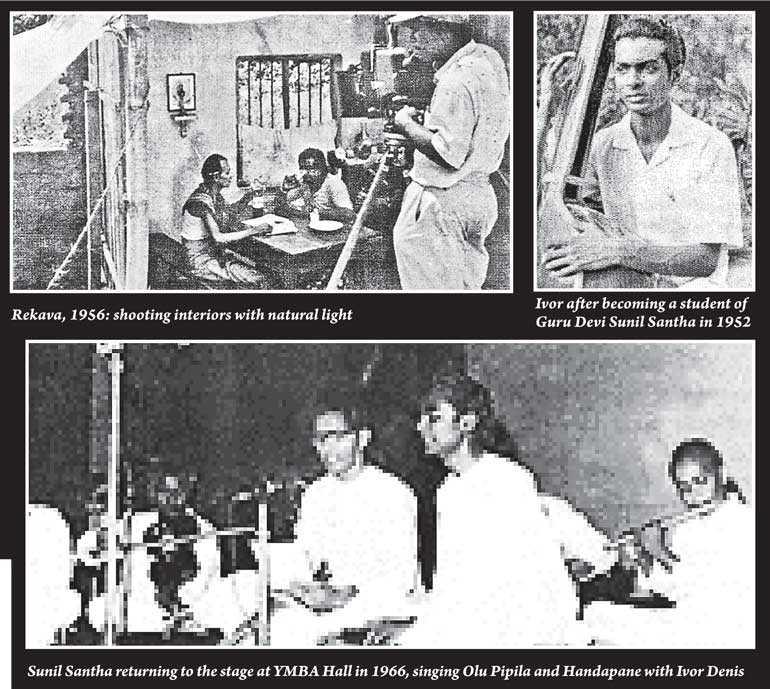

It was also uncanny that Ivor, Lester and Neville should pass away so close to each other in the first six months of last year because the three were connected to a seminal period in Sinhala film history in the 1950s marked by Lester’s first two full-length feature films – Rekava (The Line of Destiny, 1956) which Lester describes as “an indictment against rural superstitions,” and Sandesaya (The Message, 1959), which was set in Portuguese colonial Ceylon. The music for the songs in the two films were composed by Sunil Santha. Ivor led the singers in recording the songs while Neville designed the posters for Sandesaya.

Lester seemed to know everyone in the Sri Lankan arts from actors to artists, composers, poets and writers. He knew Neville and his artist wife Sybil Keyt. He attended their art shows, and in 1999, he opened a painting and drawing exhibition by Sybil and Neville at the Barefoot Gallery in Colombo. He was one of the very few able to transcend artistic and cultural boundaries in Sri Lanka and was never taken in by intellectual ideologies or cultural orthodoxy that plagued Sinhala music.

I spent a morning with Ivor in late 2016 joined by fellow Sunil Santha supporters Vijith Kumar Senaratne, Lloyd Fernando and Daya Dissanayake. As I stepped into his home in Seeduwa, the noise from the busy Colombo road was terrific and I wondered how Ivor could live next to it. The noise made it impossible to interview him there so Lloyd drove us a short distance away to a quiet spot in Kindigoda and we did the interview in a church.

Ivor was born Pasquwalge Don Augustin Ivor Denis in Seeduwa on 28 May 1932. He was educated at Maris Stella College and Loyola College in Negombo. He made an early mark with English and Sinhala, but it was a talent for music – which emerged when he began singing at school at the age of 12 – that was to set the pattern for the rest of his life. His father was Francis Aloysius – a land proprietor and regular churchgoer who played organ and sang in the church choir, but Ivor credits his mother, Maria Rodrigo, for introducing him to the music of Sunil Santha.

In 1952, aged 20, Ivor sang a Sunil Santha song called Varen heen sere, ridi valave in a music program broadcast on Radio Ceylon. Sunil was listening and thought he was singing the song until he heard a mistake and realised it was a different singer. Sunil asked his student Patrick Denipitya whether he knew this young singer. Patrick replied, “I know him very well. He is my good friend.” “Please bring him to my hotel. I would like to meet him.”

The meeting took place at the Siri Sanda Hotel in Bambalapitiya where Sunil was living at the time. Though it was only a brief ten-minute meeting, Ivor regarded those precious moments as one of the great pleasures in his life. Ivor’s first impressions of Sunil Santha were: “He was a very popular artist but a simple person in his talk and dress.” During the conversation, Sunil asked Ivor if he would like to sing with him for a Jayantha Weerasekara Commemoration Program. Ivor accepted the invitation. He was thrilled to be given the opportunity to sing with Guru Devi Sunil Santha.

Jayantha Weerasekara was an influential figure in the life of Sunil Santha. He was a journalist, a Sinhala scholar, and a leading figure in the Hela Havula – a movement of poets and intellectuals seeking to promote a refined and disciplined style of Sinhala. Sunil’s first contact with the movement took place in 1942 when he met its leader Munidasa Cumaratunga (1887-1944) but his influence on Sunil was not immediate. It was only after he died in 1944, that his successor Jayantha Weerasekera finally persuaded Sunil to join the Hela Havula which may explain why Sunil decided to sing a commemoration song for him.

The Weerasekara event took place at the YMBA Hall in Borella on 18 July 1952 – the fourth anniversary of his death. This was the first time Sunil and Ivor performed together in public. The song sung that day was Hitha Atha Paa – a commemoration song written for Weerasekara with lyrics by Amarasiri Gunawadu and music composed by Sunil Santha. The audience were ecstatic to see Ivor with Sunil. After the performance, Sunil praised Ivor for singing the song well and invited him to join his music classes.

Ivor’s parents didn’t want him to study under Sunil Santha or any musician because they were perceived as having a low social status. But Sunil told Ivor he was “embarking on a different journey” and even if musicians were not held in high regard, this was not a reason for his parents to be afraid of him studying music under Sunil Santha. Ivor’s parents accepted the argument and changed their minds and supported his decision to join Sunil’s music classes.

Ivor studied with Sunil Santha for over three years. Each lesson went for one hour and consisted of exercises and learning the fundamentals of singing and music by studying North Indian ragas and south Indian music. Sunil didn’t teach Western music, and though he was known for composing music devoid of Indian influences, he still felt Indian classical raga music provided a good method for teaching music to his students.

Ivor’s association with Sunil began around the time his guru was removed from Radio Ceylon for refusing to audition for Professor Ratanjankar. Sunil never discussed the subject with Ivor, but he could see Sunil was “disgusted” and unhappy about being kept away from Radio Ceylon, particularly during the most creative period of his life when he had the opportunity to compose many new songs.

After completing his music studies in 1956, Ivor took part in most of the music programs and projects organised by Sunil Santha. His first major project was in the film Rekava. Sunil initially refused Lester’s request to compose the songs for the film but finally agreed on condition that Fr. Marcelline Jayakody write the lyrics for the songs, B. S. Perera direct the music, and Ivor lead the singers.

The first attempt to record the Rekava songs took place in early 1956 at the Government Film Unit studio. Lester had connections there as he had previously made three films with the British documentary filmmaker Ralph Keene who had taken charge of the Government Film Unit as a guest producer.

The songs recorded were Anurapura Polonnaruva – a vrindu sung by Ivor Denis to the accompaniment of a rabana and talampotta; and Sigiri landakage – a beautiful lullaby performed by Lata Walpola to an accompaniment of three violins, cello, guitar and bass guitar. However, Lester was dissatisfied with the technical quality of the recordings and he decided to record the music at a studio with better facilities in Madras. He arranged air flights and accommodation for the singers.

In April, Ivor flew to Madras with Sisira Senaratne, Indrani Wijayabandara, and Tilakasiri Fernando. The singers checked into a hotel in Egmont and celebrated the Sinhala New Year together. The recording sessions took place over two weeks at the Vahini Studio with an orchestra comprising Indian musicians. The instruments included violins, cello, guitar, mandolin, a wooden xylophone, and tabla. Tilakasiri Fernando played violin with the orchestra.

As the leader of the Sinhala orchestra at Radio Ceylon, B. S. Perera was familiar with Sunil Santha’s style of orchestration. His orchestrations achieved a rich texture suitable for the melodic and rhythmic structures of Sunil Santha’s music. In directing the singers, Ivor found the main challenge was in the lyrics because it was important for Sunil Santha that the words of his songs be pronounced in correct Sinhala.

The combination of B. S. Perera directing the music and Ivor leading the singers was magical and the results were sublime as seen in Olu Nelum Neliya Rangala – a joyful song used in the scene of a boatman going down a river set against a verdant background. But though Rekava was a breakthrough in Sinhala cinema and the music was superb, the film was “a total disaster at the box office”. Lester later realised the film was completely outside what audiences were accustomed to seeing in the Sinhala cinema such as love scenes, dances or fights.

When Ivor returned to Sri Lanka, he continued to develop his career. In 1958, he was appointed an A-Grade Recording Artist at Radio Ceylon. In 1959, he obtained his first teaching appointment at Gatangama Vidyalaya – a government school in Ratnapura. He taught music, especially Sinhala folksongs.

After the release of Rekava in December 1956, it took Lester a year before embarking on his next film – Sandesaya. The project began in early 1958 when Lester met William Blake to discuss making a film based on the Portuguese occupation of Ceylon. The film took 18 months to complete.

In an article published in the Ceylon Daily News on 22 October 1959, Lester discussed the challenges and problems in making the film which involved researching the history of Portuguese colonisation, devising a screenplay, obtaining funding, scouting out a location to shoot the film, recruiting technicians and actors, commissioning and recording the music, and shooting the film on celluloid.

Sandesaya was set around a Portuguese garrison during the colonial period. Colonisation is acutely felt and so Sinhalese leaders in the low-country meet secretly to send a message to the King of Kandy in the central highlands, which was free of foreign occupation. In their message, the low-country leaders say they would be ready to join in an attack launched by the king against the colonial invaders to drive them out. Woven into this narrative are songs, dances and antics.

The lyrics for the Sandesaya songs were written by Arisen Ahubudu with music composed by Sunil Santha. Ivor was selected again to lead a group of Sinhalese singers to India but this time, he had to take leave without pay from his teaching job in Ratnapura. The singers were Mohideen Baig, Lata and Dharmadasa Walpola, Sydney Attygala, and H. R. Jothipala. The singers flew to Madras to record the songs for the film which took place in a different recording studio. However, the music didn’t work out as expected.

The film was produced by K. Gunaratnam – the Managing Director of Cinemas Limited. He appointed R. Muttusamy as Music Director for the film as he knew him and because he had previously provided music to several productions for Cinemas Limited. However, he began tampering with certain aspects of the music without having a firm grasp of how Sunil Santha used melodic motifs in the orchestrations to unify his song compositions.

Though Sandesaya was a commercial success at the box office, for Ivor the recording sessions were unpleasant, and for the composer the results were unsatisfactory, as Ivor explained in an interview filmed in December 2016.

“Muttusamy was credited as music director for Sandesaya. However, apart from a little directing and changing part of the melody of Puruthugeesi Kaarayaa, he mainly spent his time sitting on a chair. Most of the music was directed by an Indian musician in the orchestra, not Muttusamy. The Indian musician orchestrated the music and thought it was a good idea to use a shehnai. I could see they were not following Sunil Santha’s style of orchestration, but I had no choice. We had to sing the songs. It was an obligation.

“When the recording sessions were over, I flew back to Colombo and visited Mr. Sunil Santha at his home. He asked me about the recordings and was very displeased to learn the melody of Puruthugeesi Kaarayaa had been changed and that a shehnai had been used in his songs.”

In an interview recorded five months earlier by Daya Dissanayake, Ivor said he did raise an objection to the shehnai being used in the Sandesaya songs, but Muttusamy didn’t listen to him and dismissed his concerns.

At the premiere of Sandesaya in late 1959, Sunil Santha walked out of the theatre when he saw his song Ko Hathuro had been used as background music for the opening titles. Sunil Santha had composed this special warrior song with great care and effort for a scene in the film. Lester’s explanation for using the song as background music was that no funding was available to do the scene for which the song had been composed.

There are certain indications that other factors besides money may have been involved in sabotaging the song. As Lanka Santha points out, while the film has scenes of many Sinhalese being killed, the song Ko Hathuro expresses the power and belligerence of the Sinhalese against an enemy, and Gunaratnam, being a Tamil, may not have wanted such a scene in the film.

After returning to his teaching post in Ratnapura, Ivor received an invitation in the early 1960s from W.B. Makuloluwa to join two of his music dramas called Hela Mihira and Depano as the leading singer and main actor. These two dramas gave Ivor the opportunity to display his versatility as an actor and singer of Sinhala folk songs.

In 1966, after an absence of 16 years, Sunil Santha returned to the stage for a special musical show at the YMBA Hall in Borella to celebrate the occasion of Radio Ceylon changing its name to the Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation (SLBC). Here, Ivor joined Sunil on the stage to sing Olu Pipila and Handapane.

With his return to SLBC, Sunil began composing new songs for two popular radio programs called Madhura Madua and Pancha Madhura. Ivor was involved in every program. The process would begin after Sunil received a letter from SLBC notifying him the date for recording a specific program. He would start composing songs, and when he had sufficient material for a 30-minute program, he would give the lyrics and notation of the melodies to Ivor to practice. On the day of the recording, Sunil would set out in his little Bug Fiat with his eldest son. He would drive to Ivor’s home, pick him up and drive to SLBC.

One of the most moving moments of our interview occurred while Ivor was giving an account of Sunil Santha’s funeral procession. As he walked through the streets of Ja-Ela in the procession, Ivor sang the song Paan tharuwa netha hela gee ambare. The lyrics of the song were penned by Arisen Ahubudu and music by Ivor Denis.

It was bizarre that SLBC did not consider this historic song worthy of recording and though Ivor continued to sing the song at Sunil Santha commemorative events, it was never recorded. It reminds us that while Ivor was widely known for singing Sunil Santha songs, he was also a composer in his own right. Some of his finest melodic inventions can be heard in songs such as Abhimananiya wu navodaye and Nilwala Ganga.

After Sunil died, his daughter Kala was encouraged or “pushed” into music by her mother. In the mid-1980s Ivor started to come to their home in Rajagiriya to give Kala singing lessons. Sunil Santha Junior bought a keyboard so the two could practice music and sing together. Sunil had taught Ivor for free in the 1950s, and now he returned the favour by teaching Kala for free.

Ivor and Kala went on to record a cassette titled Guwan Thotilla which was produced by Leela Sunil Santha. They recorded the songs Bovitiya dam, Guwan thotilley, Ira besa yanney, Komala detha naga and Leney which were composed by Sunil Santha. Kala later released it as a CD. She also produced a CD with Sigiri Gee originals which was released as an EP by SLBC (Senaratne, 2018).

In a career stretching over five decades, Ivor was honoured with awards including the Presidential Award for the best Playback Singer in the film Hima Kathara, and the prestigious Kala Keerthi award which was presented to him by President Maithripala Sirisena at the National Honours 2017 festival. But for all these achievements, which he rightly deserved, Ivor always felt blessed and fortunate to have been attached to a major talent in Sunil Santha.

(Reproduced courtesy of CEYLANKAN.)