Friday Feb 27, 2026

Friday Feb 27, 2026

Monday, 20 January 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Climate change is already having substantial physical impacts at a local level in regions across the world, and the affected regions are likely to grow in number and size.

A new report from the McKinsey Global Institute on the socioeconomic risks of the changing climate suggests that many assumptions about the nature of the risk and the potential damage it could cause need to be revisited.

The report, Climate risk and response: Physical hazards and socioeconomic impacts, draws on climate model projections to highlight how a continuously changing climate creates new risks and uncertainties in the next three decades, and what steps can be taken to manage them.

It is estimated that the inherent risk from climate change without adaptation and mitigation to size the potential impact and highlight the case for action. The estimates use the Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) 8.5 scenario of greenhouse gas concentration because the higher-emission scenario it portrays makes it possible to assess physical risk in the absence of further decarbonisation.

The result of a yearlong research effort in collaboration with McKinsey’s Sustainability and Risk practices, this report focuses on physical risk, that is, the risks arising from the physical effects of climate change, including the potential effects on people, communities, natural and physical capital, and economic activity, and the implications for companies, governments, financial institutions, and individuals.

The report takes a micro and macro approach. It exposes climate risks through nine case studies that are leading-edge examples of climate change impacts.

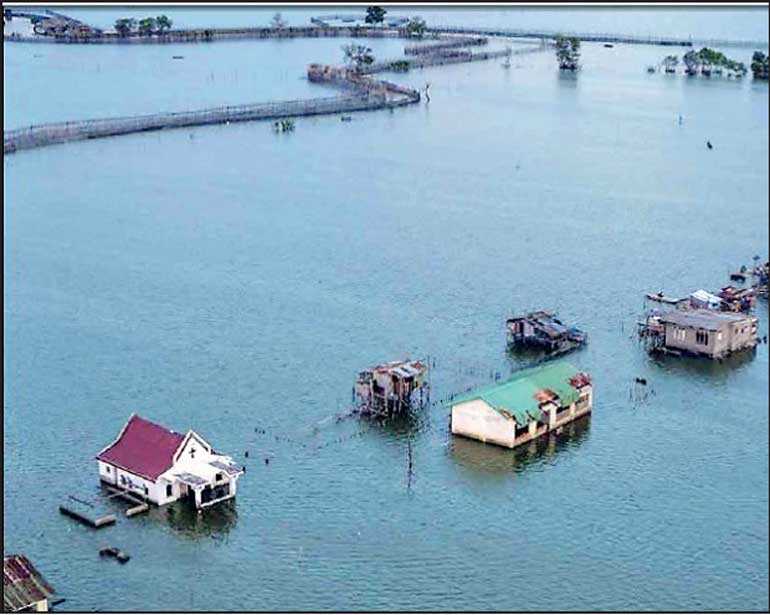

Specifically, they looked at the impact of climate change on liveability and workability in India and the Mediterranean; disruption of food systems through looking at global breadbaskets and African agriculture; physical asset destruction in residential real estate in Florida and in supply chains for semiconductors and heavy rare earth metals; disruption of five types of infrastructure services and, in particular, the threat of flooding to urban areas; and destruction of natural capital through impacts on glaciers, oceans, and forests. A separate geospatial assessment examines six indicators to assess potential socioeconomic impact in 105 countries.

“Much as thinking about information systems and cyber-risks has become integrated into corporate and public-sector decision-making, climate change and its resulting risks will also need to feature as a major factor in decisions,” said McKinsey Global Institute Director and McKinsey Shanghai Senior Partner Jonathan Woetzel.

“The intent of this report is to clarify and quantify the level of systemic physical risk that is currently accumulating, so that it can be taken into account by insurers, investors, lenders, governments, regulators, non-financial corporations and individuals as they make strategic decisions.”

Findings from the analysis

Climate change is already having substantial physical impacts at a local level in regions across the world; the affected regions will continue to grow in number and size. As the climate continues to change for the next decade and probably beyond, the number and size of regions affected by substantial physical impacts will continue to grow. This will have direct effects on socioeconomic systems in five areas: liveability and workability, food systems, physical assets, infrastructure services, and natural capital.

The socioeconomic impacts of climate change will likely be ‘nonlinear’ as system thresholds are breached and have knock-on effects. Socioeconomic systems have evolved or been optimised over time for historical climates. Societies and systems most at risk are close to physical and biological thresholds. Once thresholds are breached, impacts could be nonlinear.

For example, as heat and humidity increase in India, by 2030 under an RCP 8.5 scenario, between 160 million and 200 million people could live in regions with a 5% average annual probability of experiencing a heat wave that exceeds the survivability threshold for a healthy human being, absent an adaptation response.

Outdoor labour productivity is also expected to be impacted, reducing the effective number of hours that can be worked outdoors. By 2030, the average number of lost daylight working hours in India could increase to the point where between 2.5 and 4.5% of GDP could be at risk annually, according to our estimates.

The global socioeconomic impacts of climate change could be substantial, directly affecting human beings, and physical and natural capital. The analysis finds that all 105 countries examined could experience an increase in at least one type of risk to their stock of human, physical and natural capital by 2030. For example, the number of people at risk of experiencing lethal heat waves could rise from zero today to 250 million to 360 million by 2030, with a 9% annual probability of occurring, and to 700 million to 1.2 billion by 2050 with a 14% annual probability of occurring (under an RCP 8.5 scenario and not factoring in air conditioner penetration).

Knock-on impacts from climate hazards could affect employment, incomes, and connected sectors. Ocean warming could reduce fish catches, for example, affecting the livelihoods of 650 million to 800 million people, who rely on fishing revenue.

Financial markets could bring forward risk recognition in affected regions, with consequences for capital allocation and insurance. Greater understanding of climate risk could change risk recognition including making long-duration borrowing unavailable, reduce insurance cost and availability, and reduce terminal values. In Florida, for example, estimates based on past trends suggest that losses from flooding could devalue exposed homes by $ 30 billion to $ 80 billion, or 15 to 35%, by 2050, all else being equal.

Countries and regions with lower per capita GDP levels are generally more at risk. Poorer regions often rely more heavily on natural capital, work more outdoors, and have climates closer to physical thresholds. Climate change could also benefit some regions. For example, rising temperatures could improve crop yields in Canada.

Addressing physical climate risk will require more systematic risk management, accelerating both adaptation and decarbonisation. All key business and policy decisions need to be examined through the lens of climate change. Adaptation can help manage risks, even though this could prove costly for affected regions and entail hard choices.

Preparations for adaptation – whether seawalls, cooling shelters, or drought-resistant crops – will need ongoing and collective attention, particularly about where to invest. While adaptation is now urgent, and there are many adaptation opportunities, climate science tells us that further increases in warming and risk can only be stopped by achieving zero net greenhouse gas emissions.

“We were surprised by the magnitude and timing of these physical risks, and their potential impact on human lives, natural systems, the economy and the financial system,” said Senior Partner in San Francisco and Leader of McKinsey’s Sustainability practice globally Dickon Pinner.

“While this report demonstrates the tremendous consequences that a changing climate may have on all of humanity, it also provides a new set of tools and methodologies for decision-makers to assess risk and take what is now urgently needed action.”

The report draws on the most widely used and thoroughly peer-reviewed ensemble of climate models to estimate the probabilities of relevant climate events occurring and examine the potential impact of these events.

Woods Hole Research Center (WHRC) produced much of the scientific analyses of physical climate hazards in this report. Methodological design and results were independently reviewed by senior scientists at the University of Oxford’s Environmental Change Institute to ensure impartiality and test the scientific foundation for the new analyses in this report.

“We won’t solve climate change without involvement from the private sector, and Woods Hole Research Center is proud to be part of the process of making that happen. The most influential leaders in the private sector must be at the table and engaged in the process of finding solutions,” said WHRC President and Executive Director Dr. Philip B. Duffy.

The complete physical climate risk and response report, including detailed findings, the specific case studies and recommendations for change, is available at www.McKinsey.com/climaterisk.