Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Thursday, 24 October 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Waste in Sri Lanka, collected or not, which is not reused or recycled, ends up in either landfill, composting, open burning or illegal dumping. It is nothing new that all these types of disposal pose a threat to society and environment and finally a country’s economy as well – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

Zero Waste is a concept, which focuses on waste prevention where essentially resource life cycles are redesigned in such a way that all products are used and no waste is created. It is well-aligned with a circular economy approach, which facilitates circular product cycles instead of linear ones. The ultimate goal is it to send zero waste to landfills, incinerators or other ‘ends’ of a linear waste approach.

The Zero Waste International Alliance (ZWIA) defines zero waste as ‘the conservation of all resources by means of responsible production, consumption, reuse and recovery of all products, packaging and materials without burning them, and without discharges to land, water, or air that threaten the environment or human health’.

Rather than focusing on recycling or reusing or repairing, zero waste really aims at restructuring and redesigning products and supply chains. Its objective is to reduce waste from the start. Recently a number of initiatives have started globally where shops offer their products without packaging, individuals showcase how they live a 0-waste lifestyle, pressure on organisations is rising on supplying consumers with more responsibly packaged products, and so on. It is a trend, a lifestyle, a concept, which comes close to the ideal we all wish to have in this world. Hence, still be able to consume without feeling the guilt and burden of creating enormous amounts of waste, ending up in land or ocean.

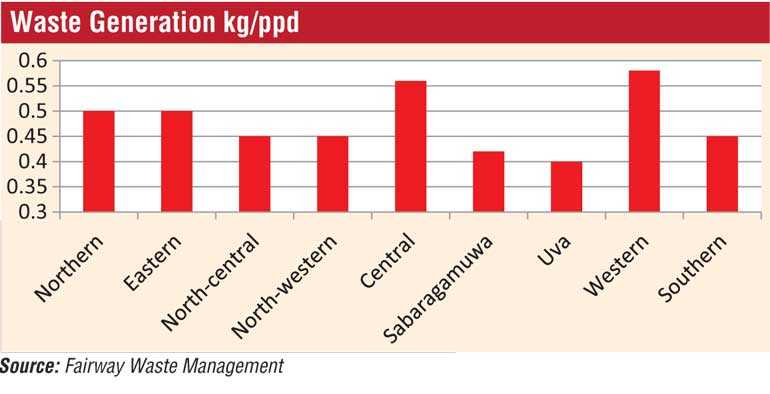

Where some countries are better in managing waste than others – Sri Lanka currently manages about 33% of its waste (50% in Western Province, 88% in Colombo metro). In Sri Lanka the total estimated waste generation island wide is 10,750 MT per day with 33% of this waste generated in the Western Province. We have 349 end disposal sites around the country with 52 in the Western Province alone.

For Colombo waste composition includes short-term biodegradables (53%), long-term biodegradables (19%), Polythene/Plastics/PVC (18%), 7% paper (7%) and other waste (3%) – considering that waste composition is dynamic and depends on several short and long term factors (time of the year, location, consumer habits, ..). Waste in Sri Lanka, collected or not, which is not reused or recycled, ends up in either landfill, composting, open burning or illegal dumping. It is nothing new that all these types of disposal pose a threat to society and environment and finally a country’s economy as well.

What many are not aware of is that end of the day, ‘all’ waste which is not biologically degradable, recycled or reused will end up in the ocean. Via a country’s streams and canals, in whatever microform the waste might be already degraded, it will finally end up in the ocean. We heard about the large garbage patches floating in the sea, this is besides the micro plastics and particles which we can’t see with our bare eyes, hence research has confirmed that around Sri Lanka for all tests being done, all surveyed marine life was contaminated with microplastics.

In addition to that, we all remember the collapse of the Meethotamulla Landfill not too long ago, we see the polluted habitats in sea, coast and on land, we see elephants, birds, cows and all sorts of other animals feeding on waste dumped either besides roads or in parks, we read stories of those animals dying of ingestion, entanglement and smothering, we read about explosions at landfill sites, we witness waste being transported from one place to another to be dumped again …. And at the same time we hope for zero waste, to become a dream come true.

When looking at statistics, some countries have much higher per capita waste generation, however less waste issues as they are able to manage the waste better. Their collection, recycling and disposal systems are much more sophisticated and, in some incidents, no solid waste ends up in land or water. This does by far not mean that consumers are more responsible or products are designed more innovatively to create less waste. Rather, in times of Amazon and Co, consumption patterns of developed countries are much more worrisome than those of the average Sri Lankan.

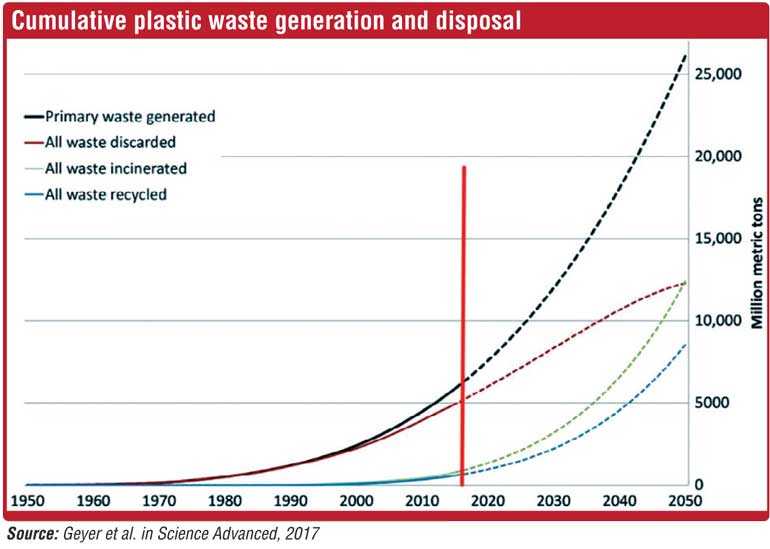

Globally, plastic waste generation has increased exorbitantly during the past few years where approximately 55% of this plastic is discarded, 25% is incinerated and 20% is recycled. Here it is necessary to mention that the very often cited Science article of Jambeck et al (2015) on ‘Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean’ which lists Sri Lanka as the 5th largest polluter is completely wrong (Sri Lanka is not even among the first 20 countries). The data the authors used had been incorrect, a fact which was acknowledged by the authors later on. Nevertheless, this research article continues to be the basis for various reports and documentaries, really not giving justice to the Sri Lankan ground reality.

Consumers cannot carry the burden alone

Now we all know the global waste situation, including Sri Lanka, is worrisome. To really make a change we have to reduce consuming. Waste has to be avoided in the first place. This includes consumers globally buying less overall, if purchasing then choosing products with less waste over others, reusing products, repairing items and segregating the final accumulated waste, composting organic wastes and sorting the remaining items so that they can be recycled.

On the other hand, companies need to change their products as well as the packaging they use. Products have to be aligned with a circular economy approach having in mind that no item of a product will end of the day end up in landfill. Packaging has to be suitable and efficient, we all know that, however there is large room for improvement. A society cannot expect consumers to carry the burden alone. In addition to recycling, items can be upcycled as well giving them another lifetime, or hopefully multiple lifetimes.

Visiting Royal College last week I got to know that the campus, hosting currently almost 10,000 students, includes cafeterias to supply snacks and drinks to the pupils and teachers. As all across Sri Lanka, drinks such as Milo or Smak are a favourite amongst kids. Estimating that at least one third of students purchase one of these drinks a few times a week, this amounts up to thousands of packages, straws and other plastic parts being disposed on site. It is on the company to offer alternative packaging, which is suitable and sustainable.

We know what needs to be done, but we also know that this will take time. At the rate we currently globally generate waste, we cannot balance out the waste we have already created plus the waste we newly create each day with the rate above mentioned measures are currently implemented. Hence alternative methods have to be put in place to help and sort out the mess we have already created! Such solutions include thermal treatment of inorganic waste, biological treatment of organic waste and sanitary engineered landfills for end products.

These approaches are not acknowledged by the 0-waste community as they contribute to a linear waste management approach. Also, some critical voices are concerned that waste to energy plants would generate a need for more waste supply instead of reducing waste. Fact is, the world has always produced and will in the near future produce sufficient waste for such plants, consumers as well as companies – as sad as it is – are not going to change fast enough.

Change will happen slowly

Despite the numerous efforts of the 0-waste community and increased awareness among the public as well as leaders, we have to accept that change will happen slowly. Behaviour change is hard for humans, this is a fact, and we see that from history and every day in multiple areas of life. Hence, we are still dependent on let’s call it ‘not ideal’ solutions to sort out our waste issue.

In the Sri Lankan context, looking at waste to energy, a new plant is proposed including the highest standards making it a best practice example for the region. Not every solution, which is available globally suits our context, this plant seems a good choice. The status quo of Sri Lanka as described above, which essentially means: landfill, mismanaged waste, all waste goes into the ocean is not one that is sustainable.

Having faced criticism some weeks back as being ‘too expensive’ for Sri Lanka as a solution, it is not understandable how a fully privately funded waste to energy project such as the envisaged plant could be too expensive for the country. Development, operation nor maintenance do not cost the taxpayer a single cent; unlike the landfills; i.e. Aruwakka’s approximate cost is Rs. 25 billion tax money not even looking at interest cost.

We know what needs to be done, but we also know that this will take time. At the rate we currently globally generate waste, we cannot balance out the waste we have already created plus the waste we newly create each day with the rate above mentioned measures are currently implemented. Hence alternative methods have to be put in place to help and sort out the mess we have already created! Such solutions include thermal treatment of inorganic waste, biological treatment of organic waste and sanitary engineered landfills for end products

In addition most of the money goes to Chinese contractors where the local companies miss out. How many projects has the country started or implemented which cost the taxpayer billions without any significant impact? It was also said that the waste is too moist so the plant would only be able to generate 20-30% energy. Even if the waste was dry, waste to energy conversion efficiency to electricity is around 30% in general using available technologies.

When testing the waste on project site, it was found that it exceeds the World Bank’s values in its guidelines for planning a waste to energy project, therefore it is more than suitable for the plant. Comparing the waste to energy plant with the sanitary landfill in Aruwakkal as the latter being the favoured solution; sanitary landfills should only be used for the final waste as much as possible; such as for ashes from incineration and incombustible waste. Transporting mixed waste via trucks and trains for kilometres into a sanitary landfill, is not a solution at all! Mostly one argument of the critics of the proposed waste to energy plant struck me: “Sri Lanka has 60% of food waste and if plastics are also recycled, there is nothing to burn at the plant. There is always an overestimation in the amount of waste, it is at a manageable level.”

Countrywide ‘only’ 33% of waste is collected as we read above, how can this be called manageable? Even the collected waste ends up in landfills and the rest in land and water. Who is going to recycle all the plastic? So far everyone is hunting for PET bottles, those are not the real problem. In any chase only 14% of the waste consists of plastics, so there is 85% of waste left for the plant (after reducing glass, metal, and others which cannot be burned). The proposed project will include a biological processing unit and a thermo physical treatment unit.

The argument that there is not enough material available in Sri Lanka to supply recycling plants is partially true. There would be enough material available if it was segregated and collected. I do in no way say waste to energy is the top solution, ‘only’ behaviour change at all levels is! However end of the day, this plant does not cost the Government or taxpayer a cent, it intends to take out waste which we anyways produce until we finally change our behaviour to a significant degree (there is a strong correlation between GDP rise and waste generation), it exceeds the quality requirements and supplies electricity, which we also need.

The critics so far also miss to propose sustainable alternative solutions (other than landfilling), therefore their arguments can hardly be taken serious within the discourse on how to solve the waste challenge in this country.