Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Friday, 29 June 2018 00:25 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The exchange rate is making headlines these days. If there is anything that has beaten all expectations, it is the exchange rate. The abrupt and volatile behavior of exchanges rates has given a hard time for policymakers in the emerging economies.

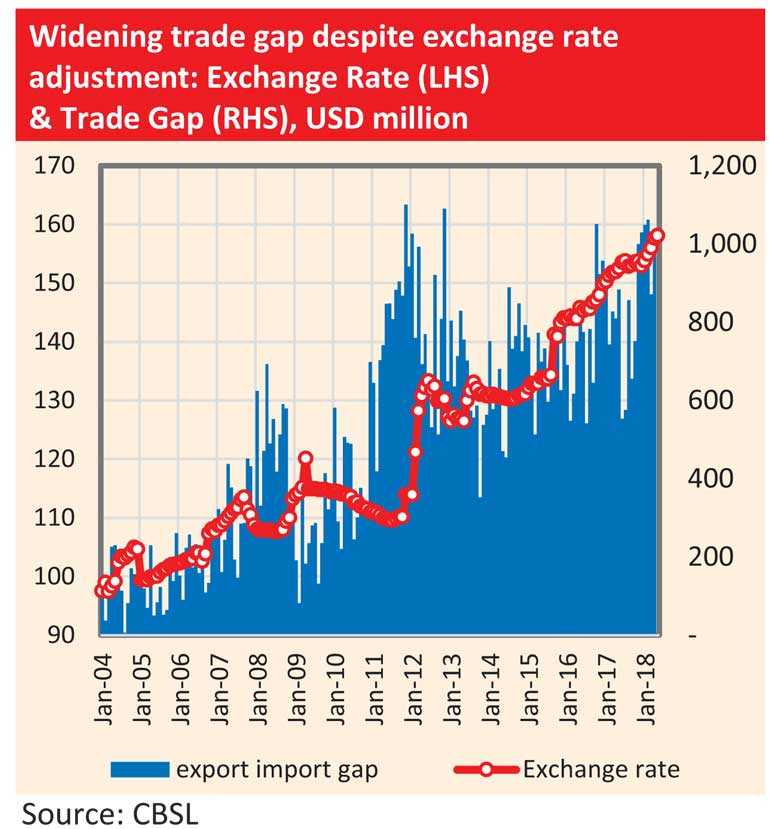

Exchange rate depreciation or a weak local currency is believed to be good for increasing exports, making local assets more competitive globally and curtailing unwanted imports. Such a movement, in theory, should help to keep local currency closer to its real value and thereby increasing exports and lowering imports.

On the other hand, in an era of reversing capital flows back to the US and developed world, policymakers in emerging economies must be choosing weaker currency over higher interest rates, which in turn negatively affect the economic growth.

Inflation

However, there are reasons to worry over the sharp depreciation of local currency. The biggest concern of the policymakers is inflation, known as imported inflation. Weaker currency could increase the import cost of essentials and jeopardise price stability. The persistence increase in general price level of the economy through higher import prices is identified as imported inflation which could distort the economic decisions. Sharp depreciation may hamper the fight against inflation in a country where prices respond quickly to currency weakness.

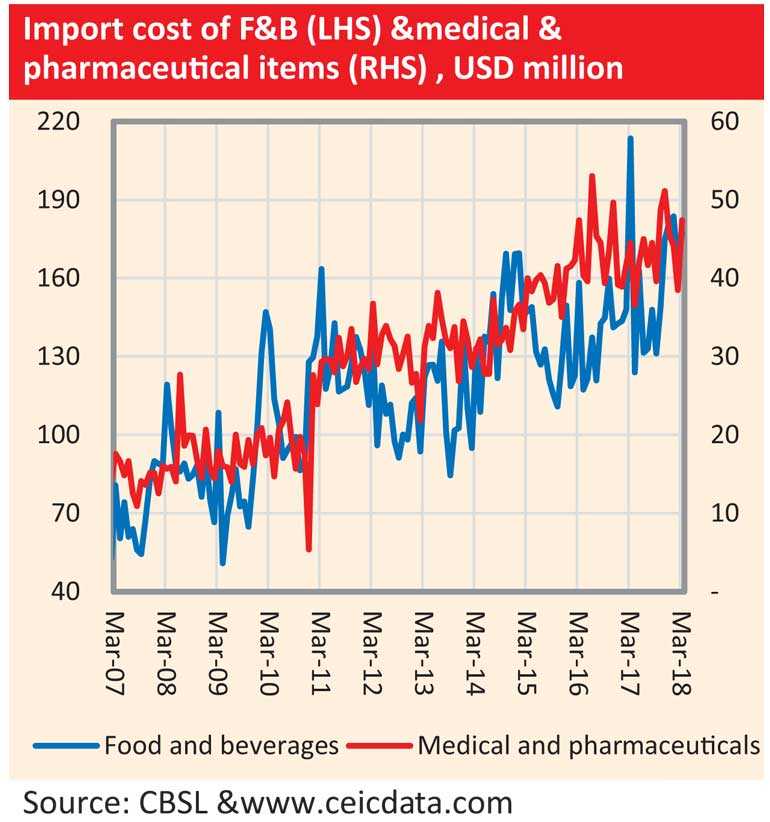

Sri Lanka is dependent on imports for many essentials – fuel, food and beverages (such as vegetables, sugar, cereals and dairy products), and medical and pharmaceuticals. Depreciation of local currency directly increases the cost of such essentials jeopardising thousands of lives. Furthermore, price increase in energy and other food inputs may feeds into a cycle through price revisions in many downstream industries.

In summary, the impact of a strong dollar is dependent on two factors – level of accommodation and structural factors of the economy. If the external shocks are accommodated through expansionary monetary policies, the impact will be inflationary. If the economy depends on import for key essential goods, there will be a higher inflationary effect.

External debt

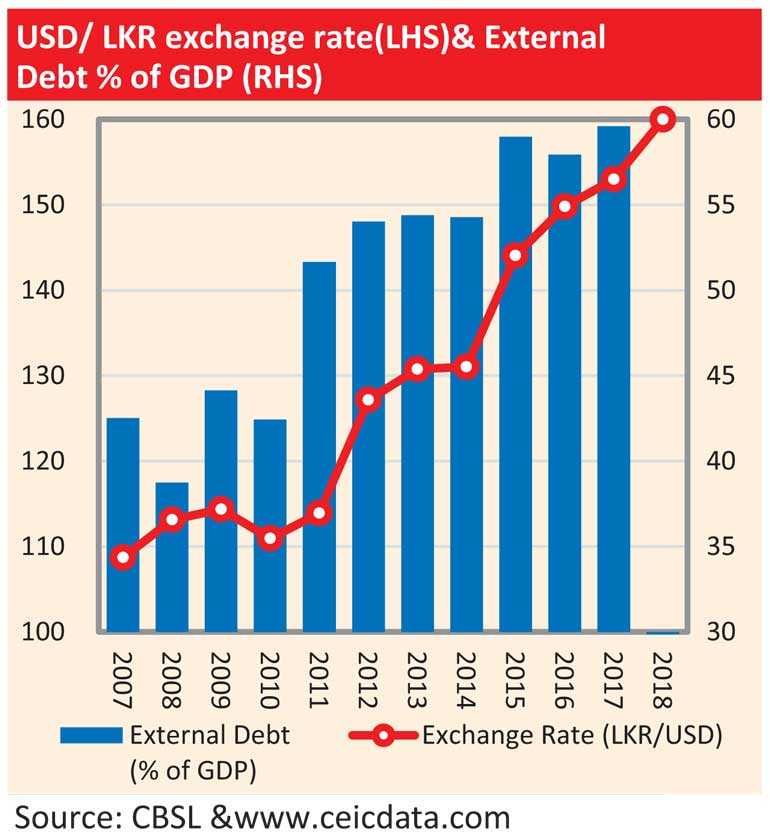

The next reason is external debt. A weaker local currency increases foreign currency denominated liabilities. Many emerging markets had received a large inflow of foreign debt due to an ultra-low interest rate environment which prevailed in the developed world (US and Europe). The exit of quantitative easing and increase in the benchmark interest rates by developed world central banks have triggered a reversal of capital flows back to the developed world. Though there is no nominal change in foreign liabilities as a result of exchange rate depreciation, it may inflate the value of the debt stock in local currency terms and create discomfort. If there is a gap between net foreign currency earnings and debt service payments, the lenders may be nervous.

External debt as a percentage of GDP in Sri Lanka (2017) remains high at 59.6%. Though classification is not clear, external debt as a percentage of GDP is in comparison, 53.3% in Turkey, 36.7% in Argentina, 34.7% in Indonesia, 27.2% in Pakistan, 23.3% in Philippines, and 20.1% in India. Though external debt level in Indonesia and India are comparatively low and inflation is under control, both central banks had raised policy interest rates as a pre-emptive action to stabilise the currency. Countries with high debt and stubborn inflation outlook such as Argentina and Turkey have taken a heavy beating on their respective currencies.

External debt as a percentage of GDP in Sri Lanka (2017) remains high at 59.6%. Though classification is not clear, external debt as a percentage of GDP is in comparison, 53.3% in Turkey, 36.7% in Argentina, 34.7% in Indonesia, 27.2% in Pakistan, 23.3% in Philippines, and 20.1% in India. Though external debt level in Indonesia and India are comparatively low and inflation is under control, both central banks had raised policy interest rates as a pre-emptive action to stabilise the currency. Countries with high debt and stubborn inflation outlook such as Argentina and Turkey have taken a heavy beating on their respective currencies.

The strong dollar rally has made EM central bankers nervous about the flight of their currencies and subsequent impact on local economies. Some central banks have taken pre-emptive actions in anticipation of trouble ahead while others have been given no policy choice, except a panic policy reaction.

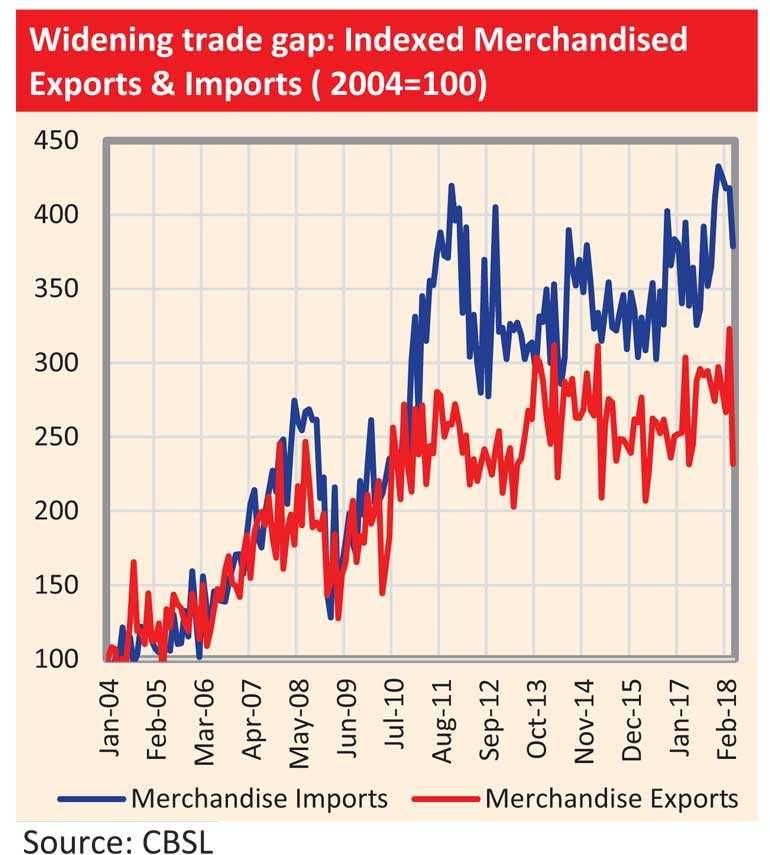

In theory, weakening local currency increase exports, make local assets more competitive, and curtail unwanted import. However, the ultimate impact depends on the structure of the economy. A country like Sri Lanka largely depends on imported consumer goods and industrial inputs (including inputs for main exports i.e. textile imports for apparel manufacturing), which may not yield a substantial benefit.

In the long run, the weaker exchange rate is not sufficient to drive exports. It requires making the country more competitive and attractive for international businesses. While competitive exchange rate helps, structural reforms including tax policy, decision consistency, labour reforms, ease of doing business, business-friendly legal jurisdiction, and private property rights are more important factors.

Without such structural economic reforms to make a country more competitive, currency depreciation alone cannot make it internationally competitive.

(The writer is a CFA charter holder, capital market specialist, and certified FRM. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any institution.)