Friday Mar 06, 2026

Friday Mar 06, 2026

Friday, 2 April 2021 00:02 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The advantage of applying systems-thinking is that it provides an understanding of the complex contextual factors that contributed to the decision-making, especially policy decisions, that ultimately paved the way for the attacks. This knowledge is essential to gain a deeper understanding of ‘how’ the Easter attacks happened, so that similar incidents may be prevented in future – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

On 21 April 2019, when my friend stepped into a hotel in Colombo with her family to enjoy the Easter brunch, she never would have imagined that this would be the last meal she was going to have or it was the last moment she was going to spend alive. Why would she have those thoughts when she and all other Sri Lankans believed the days of terror were behind us; when we believed that we lived in a safe country. But we were wrong!

On 21 April 2019, when my friend stepped into a hotel in Colombo with her family to enjoy the Easter brunch, she never would have imagined that this would be the last meal she was going to have or it was the last moment she was going to spend alive. Why would she have those thoughts when she and all other Sri Lankans believed the days of terror were behind us; when we believed that we lived in a safe country. But we were wrong!

Over 260 innocent lives were lost and twice as many injured in the devastating attacks that took place in three churches and three luxury hotels, carried out by Islamist terrorist suicide bombers on that day. Fast forward two years to 2021 – we have a new President and Government; the 20th Amendment to the constitution which reinstated most of the constitutional powers to the President; and the report of the Presidential Commission of Inquiry on the Easter Attacks is out. In addition, we have now reached a point where different parties, mainly political, try to control the narrative of who is and who is not responsible for the Easter attacks.

One of the problems with these narratives is that they often serve to polarise the issue and make people focus on only what they want us to see, not the whole picture. These narratives are subjective, often speak to people’s sentiments, and do not provide any direction towards a solution. Against this backdrop, it is therefore necessary and important to analyse the events that led up to the Easter attacks through an academic and objective lens, specifically, a systems-thinking approach.

The advantage of applying systems-thinking is that it provides an understanding of the complex contextual factors that contributed to the decision-making, especially policy decisions, that ultimately paved the way for the attacks. This knowledge is essential to gain a deeper understanding of ‘how’ the Easter attacks happened, so that similar incidents may be prevented in future.

During the last presidential election, we heard many people say that the ‘system’ needs to change. In academia, a system is described as a collection of ‘elements’ that are ‘interconnected’ and produces a behaviour to achieve a ‘goal(s)’. A simple example is a family. The ‘elements’ of a family are parents, children, house they live in, and the resources they have (e.g., wealth). The ‘interconnections’ are the practices, spoken and unspoken rules, and communication among family members. The ‘goal’ of a family could vary from being rich, live a healthy lifestyle, travel, or just survive.

Every system can be changed/re-designed, has feedback loops, has leverage points, and traps and opportunities. This article will not discuss all the elements of a system, but will focus on the core ones – the elements, interconnections, and goals. Changing the elements, interconnections, or goals can bring about a change in the system, which sometimes can have drastic, unforeseen consequences. The most important element that affects the system behaviour is, of course, the ‘goal’.

Now, let’s look at the system that was in place in April, 2019 when the Easter attacks happened.

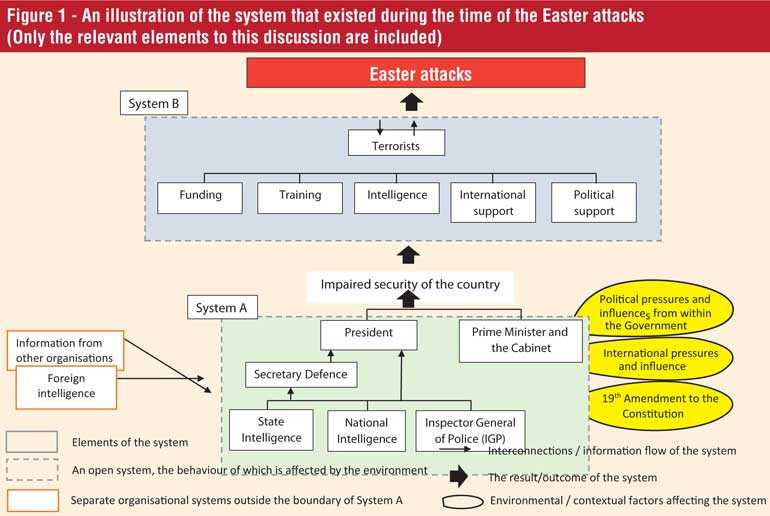

As seen in Figure 1, both System A and System B are open systems, which can be understood only in the context of its environment. This is due to various factors in the environment that impact the system. In relation to System A, political pressures and influences from the different parties of the coalition government, pressures and influences from the international community, and the changes introduced by the 19th Amendment to the Constitution are examples of environmental/contextual factors that impacted the system. In relation to System B, the most significant environmental factor that impacted the system was the impaired security of the country that enabled the terrorists to function smoothly, e.g., obtaining financial resources, having training centres and rehearsals. This article will focus on System A since adequate information is not available on System B to engage in a meaningful discussion.

Elements – designed to fail?

The report of the Presidential Commission of Inquiry on the Easter Attacks has recommended that specific elements of System A: The President, Heads of State and National Intelligence, IGP, and Secretary Defence, be prosecuted under the Penal Code. They have all been accused of failing to fulfil their duties. Leaving aside the President from this discussion at this point (because his role in the system is different to the roles of those below him), why did seemingly well-meaning people behave the way they did? Why did they fail to do their job? Or should the question be – what was their role within this system?

A person’s role within a system is decided by the system design. Therefore, if the behaviour of a person/s is undesirable from the whole system’s perspective, then there is a design error in the system. We see this happening in many systems, such as companies, where people are changed, expecting different outcomes. However, if the system is not changed, then the outcomes are very likely to remain the same, which is why it is a design error in the system.

For example, people who are labelled as underperformers leave their present organisation and join a different organisation in which they excel. The opposite is also true, where people who are hired for their track record of success, join the new company and do not perform as expected. In such instances, the problem lies with the system, not the person. So, should the focus be on the inadequate response by the people in System A or the flaw in the system design? (Of note is that the exception to this rule is at the top. The senior most person/s in the system has the power to change the system design and by doing so, the system behaviour. This is why countries keep changing their leaders periodically. Whether they act on changing the system is another discussion, for another day).

In System A, everyone below the President behaved as the system intended them to behave. For example, they were not expected to convey the important information received from the foreign intelligence to the Prime Minister or any other Minister, except the President. That is how the system was designed. They operated in a silo driven structure, not an integrated team. The actions or inactions of the people in System A need to be understood in the context of the system, not in isolation. This is when we are able to understand their behaviour, which paved the way for the attacks.

When a system is designed in such a divided manner, it makes one question the interactions/interconnections between people. Interconnections hold the elements of a system together.

What was the nature of the interconnections in System A?

Interconnections – Together yet disconnected?

What characterises a well-functioning system (e.g., an organisation) is not only the quality of the elements (e.g., employees) but also the interactions between them. In System A, a striking feature was the lack of interaction between the President and the Prime Minister. The President on multiple occasions claimed that he was unaware of certain actions taken by the Prime Minister. It was evident that there were constant clashes between the two with the President ultimately alleging there was a conspiracy to assassinate him. The rift between the two led to the President replacing Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe with Mahinda Rajapaksa and suspending Parliament in October, 2018, which flung the country in to a constitutional crisis and political limbo. A perfect environment for System B to thrive in!

In addition to the lack of interaction between the President and the Prime Minister, closer to the Easter attacks, it is evident that there was hardly any interaction between the President and his direct and indirect reports in the system. It appears that a downward communication channel was absent within the hierarchy where the President provided necessary guidance or feedback to his direct/indirect reports. This is best highlighted by the interactions between the members of the National Security Council (NSC), the executive body responsible for the national security of the country and the President who is the chairman of the NSC. The NSC had become a non-existing entity, with the members of the council changing at the whim and fancy of the President. For example, after the alleged falling out between the President and the IGP, the IGP was asked not to attend the Security Council meetings, which was the same situation involving the Prime Minister. The Commission report highlights that the Prime Minister failed to raise this as an issue in Parliament or the Cabinet due to reasons only known to him.

The most remarkable point is that the NSC did not meet regularly, which suggests how insignificant the country’s security was to the government and to the Head of State, Commander-in-Chief, and Minister of Defence and Law and Order – the President. Put simply, the sub-system of NSC was completely warped, which was a contributing factor to the creation of the unsecure environment of the country.

Was the security of the country not a priority goal of the Government? To understand a system’s goal, one needs to examine its behaviour. This is because a system can explicitly state a goal/s, but behave in a completely different manner. For example, a company that states that “our people are our greatest asset”, but allocates the least amount of funds for employees, such as for training and development, demonstrates a different behaviour from its stated goal.

The goal – reconciliation or security of the country?

Among the many goals of the Government, the goal relevant to the system under discussion is ‘reconciliation’. In 2015, soon after coming to power, the Government pledged to strengthen fundamental freedoms and the rule of law that included inclusiveness, justice, and respect for human rights to all of the people of Sri Lanka. Delivering on this pledge, the Government co-sponsored the Human Rights Council Resolution 30/1 on promoting reconciliation, accountability and human rights in Sri Lanka, and established the Office for National Unity and Reconciliation.

Perhaps the most striking decision taken by the Government, as revealed in the evidence proceedings of the Presidential Commission of Inquiry on the Easter Attacks and in the petition submitted to the Supreme Court by the IGP, is ‘not’ to investigate activities of extremist Muslim groups. This, done under the pretext of reconciliation (although the alleged ulterior motive was not to upset the minority parties that made up the coalition government), had a significant unanticipated consequence – the creation of a free environment in which System B – the terrorists – could thrive with greater ease.

A similarly alarming revelation was made a few days after the Easter attacks, on 26 April 2019, by the Prime Minister, in an interview with Sky News, when he stated that the Government was aware of the Sri Lankan citizens who had joined the Islamic State (ISIS) and returned to the country, but no action could be taken against them because joining a foreign terrorist organisation is not against the law. Being the Prime Minister of the country, an experienced statesman and lawyer, with this information in hand, what actions did he and the Government take to enhance the security of the country?

Why did the Prime Minister, who wielded immense power afforded by the 19th Amendment to the Constitution, adopt such a ‘lax approach’ (as stated in the report of the Presidential Commission of Inquiry on the Easter Attacks) towards Islamic extremism? This inaction suggests that the security of the country was not a primary goal of the Government as it potentially clashed with their other goals, e.g., reconciliation agenda.

Contrary to the Government’s approach, it may be argued that the country’s security and ethnic reconciliation did not have to be dichotomous – they did not have to be at the opposing ends of a continuum. The Government did not have to make a choice between either – or, but could’ve chosen both and ensured the country’s security whilst fostering reconciliation. However, when political interests and pressures drive government policy decisions, a likely outcome is the deterioration of the country’s safety defences.

When we put the elements, interconnections and the goal/s together, we are able to see the whole picture – the system, and have a better understanding of the behaviour and events that took place. By fixating on the parts that are only visible to us, we derive conclusions based only on those parts. This can be likened to the story of the six blind men feeling six different parts of an elephant and arriving at six different conclusions.

Looking beyond the tip of the iceberg – the Easter attacks

Adopting a systems approach allows us to focus beyond the actual attacks, which was only the tip of the iceberg, toward the underlying systemic structure and the underpinning causes. The tendency to simplify everything to a superficial level, where politicians claim “it wasn’t me” is essentially a futile attempt to conveniently shrug off responsibility and mock the public’s intelligence. Adopting a system’s approach reveals that whilst those in System B were the perpetrators of the devastating Easter attacks, those in System A were the enablers.

Coming back to the present day, the current Government does not operate within System A. The President’s contextual factors are drastically different; e.g., he has the full executive powers afforded to him by the 20th Amendment; the interactions between the President and the Prime Minister appear to be unproblematic; the intelligence agencies have been strengthened and the National Security Council is active. Since a seemingly safe and secure environment has been restored, it may be difficult for another System B to operate, but not impossible, the reason being that the elements of System B are still being investigated and there are untied loose ends. It is also imperative to examine the underpinning reasons for Islamist radicalisation in Sri Lanka and address the root issues.

When looking at the whole picture, it becomes clear that both System B – the perpetrators and System A – the enablers are responsible for the devastating Easter attacks and they both should be brought to justice. If this does not happen, the most powerful system designers, the people of the country, might decide to change the system

yet again.