Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Monday, 30 March 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

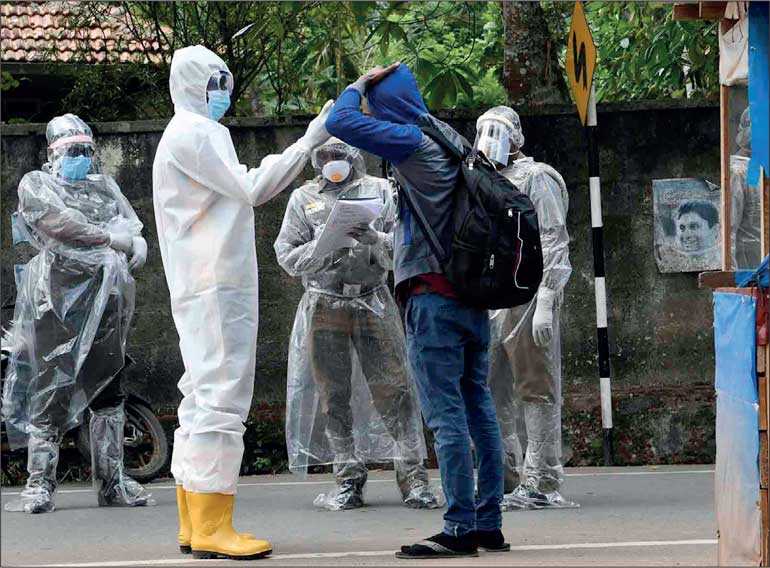

Until a vaccine is found, the world can only slow down the spread. That too at considerable cost and with extreme measures – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

We just passed a weekend filled with intoxicating anxiety. At 8 p.m. on Saturday, we learnt of the first death from COVID-19 at the IDH at Angoda. A 60-year-old male. The official announcement stressed that the man had other complications. I thought it was bloody funny about other complications.

E.H. Carr, in his meaning of history, gives an example of why added explanations don’t do any good to the truth.

A man on his way to buy a pack of cigarettes is run over by a motorist. The motorist applies brakes that did not function. The brakes did not function because the mechanic who attended to the faulty brakes had been negligent. What would history record as the cause of his death? That he was run over by a motorist? That he died on the road because he ran out of cigarettes? That he died because a mechanic was negligent?

The rest of the weekend in lockdown land I meditated on the bizarre and the bold approaches of how we approach the pandemic. I may be wrong. But this is how I read it.

The need of the hour is for solidarity and social distancing. That is not a problem for a nation that thrives on contradictions. We abhor murder and we pardon murderers. We don’t care if the murder was on a luxury high-rise or in a war-ravaged jungle.

Today’s imperative is to halt the pandemic and to hold elections to the Parliament.

Brutal reality of the pandemic

On the last day of 2019, 31 December, the Chinese State informed the World Health Organization that they had discovered a strange pneumonia vibrant in the city of Wuhan in the province of Hubei.

Since then this insidious angel of death, destruction and confusion has been named as the Covid-19 pandemic.

Thousands have died in China, Italy and elsewhere.

Saturday’s death at Angoda is our first encounter with death by pandemic. The wicked angel of death is at our doorstep.

The stoic amongst us in this age of human rights and presidential pardons say that death is a kind of birth right of every person born. A curiously clever construction of an obvious truth.

Whatever other complications the man had, he died alone at 8 p.m. at the Infectious Disease Hospital at Angoda.

He died alone while a bewildered nation stood vigil. He did not have the embrace of loved ones. His death came in a strange sanitised worlds where the living hovered around him dressed in the style of astronauts wearing protective masks, gloves and visors.

His death was in a germ-free cocoon. I am sure the doctor who attended would have looked at him kindly with forlorn eyes.

The dying man would not have seen the resigned humanity in the doctor’s eyes. He was wearing visors. Am I seeking melodrama? No. I am simply and surely disgusted with the visors of political expediency that I have seen in the past two months.

Saturday’s death at Angoda brought the brutal reality of the pandemic to Sri Lanka. A hard fact that needs lot of rubbing into those closed minds convinced of an imagined cosmic immunity that makes our island special.

Saturday’s death at Angoda had no purpose, no logic, no necessity. Hours before that death, a soldier convicted of murder was pardoned. The pardon had a logic and a purpose. But was there an urgent necessity?

The events in lockdown land during the week end reminds us of the words of August Compete the man regarded as the first philosopher of the sciences

“Humanity is always made up of more dead than living.”

Back to normalcy – When? How?

Until a vaccine is found, the world can only slow down the spread. That too at considerable cost and with extreme measures.

By remarkable coincidence, Emeritus Professor of History and History of Medicine at Yale , Frank M. Snowden, has published a great book, ‘Epidemics and Society: From the Black Death to the Present’.

Under normal circumstances I would have pestered my daughter to send it to me as she happens to live in country where bookstores keep knowledge unlike ours where they stock what sells. The lockdown prevents any early access.

The ‘New Yorker’ carries some excellent excerpts.

“Epidemic diseases are not random events that afflict societies capriciously and without warning,” writes Professor Snowden. “On the contrary, every society produces its own specific vulnerabilities. To study them is to understand that society’s structure, its standard of living, and its political priorities.”

We must ask ourselves in our collective lockdown mood “have we not produced our own specific vulnerabilities in the wake of this pandemic?”

When will life return to normal? If you think ‘life as usual’ will come back, you are in over-optimistic fantasy. In cloud cuckoo land.

That thought occurred to me when reading a Sunday broadsheet online. It speculated that Parliamentary Elections may be held by the end of May.

Every country in the world wants to flatten the curve. There are people who seriously hold the view that we could do it faster than some others. They are wrong. We may flatten the curve, but we will not negotiate the bend and restore normalcy. Normalcy comes when everybody succeeds in flattening their respective curves.

During this bleak weekend, I seriously wondered about our ruling class and the knowledge-based economy on which they often pontificate.

It is highly unlikely that any of the now defunct 225 or the current composition of the Caretaker Government has read the three books that sum up the rhythm of the 21st century universe.

They are Thomas Friedman’s ‘The World is Flat,’ Yuval Noah Hariri’s ‘Sapiens,’ and Mervyn King’s ‘The End of Alchemy’.

In ‘The World is Flat,’ the author New York Times columnist Friedman explains the 21st century connectivity of global trade and human enterprise.

In ‘Sapiens,’ the Professor of History of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem Yuval Hariri lucidly explains in ingeniously abridged from ‘The History of Humankind’.

In ‘The End of Alchemy’ Professor Mervyn King – the former Governor of the Bank of England, considered the ‘mother of all banks’ – explains the idea of paper money: Humanity’s greatest invention.

Flattening the COVID -19 curve does not mean that we will go back to normal. We all want things to go back to normal. What we don’t realise is that we will not go back to normal in a few weeks or a few months. If a vaccine is not found within a reasonable time frame, somethings never will go back to normal.

A successful city state Singapore and a resourceful siege state Israel have provided good indicators of where the world is headed.

Israel is in the process of using cell phone locating data used to track terrorists to identify carriers of the virus. Singapore has made exhaustive contact tracing into a routine procedure.

Globalisation

Globalisation began when mariners mastered the winds. The globalisation that we speak of is the vibrant international marketplace brought about by technology-driven connectivity.

Manufacturers world over built flexible supply chains. Profits peaked because substituting one supplier or component became easy across borders, oceans and continents.

Adam Smith’s ‘Wealth of Nations’ became a tome on a library shelf. ‘Wealth of the World’ can now be read on giant stock market screens in New York, London, Frankfurt, Tokyo, Seoul and Singapore.

The evidence of globalised division of labour can be seen by the number of BPOs located in Colombo when you head towards the New Kelani Bridge.

Specialisation produced greater efficiency, which in turn led to growth. The functioning growth circle is now intercepted by the pandemic virus.

It has ruptured a complex system of interdependence.

Huge enterprises dependent on global supply chain were cosily settled in tangled webs of production networks. Complex as they were, corrupt and conniving as they were, the system held the world economy together.

A component of a given product could now be made in several countries. In the wake of the pandemic companies in Palo Alto, Stuttgart, Seoul and Nagoya have realised that this cultivated specialisation, substitution is difficult. Especially the unusual skills of the Chinese cannot be replicated.

When production went global it necessarily made countries interdependent. No country can claim self-sufficiency in all the goods, components, services and raw material it needed.

The COVID-19 pandemic has devastatingly exposed the fragility of this globalised system.

In coming months, we will see who can confront the crisis and to what degree. We will then know who in which country followed Apple CEO Tim Cook’s dictum that inventory is “fundamentally evil” and adopted “just-in-time” supply chains as unimpeachable doctrine.

The pandemic has already reduced global production of laptops by 50%.

The New York-based ABI research is blunt in its prognosis.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has produced a chain of events unlike anything we have seen in our lifetimes. Our daily routines have been flooded with uncertainty, both at home and at work. This has resulted in questions about the future state of our global economy. “

The phrase ‘breaking news’ has lost its meaning. Only the oligarchs who own private TV channels think that broken news is breaking news.