Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Saturday, 10 October 2020 00:04 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Death row prisoners live in cells and wards that often lack proper ventilation and natural light due to which many long-term prisoners suffer illnesses, with the most common being problems with eyesight. In Welikada Prison for instance, death row prisoners inhabit severely overcrowded buildings that are dilapidated

The man knew his life in this world was over and looked at us and said, “Mang yannang, Sir” (“Sir, I’ll go”). It was a heart-rending scene. The bag-like head-gear was brought down to cover the prisoner’s face and neck and the noose was put round his neck. I had a feeling of despair… Here was a man who had talked to me a few minutes ago, now being killed in cold blood before my very eyes and yet I could not do anything about it. I felt sick and horrible. I felt this was murder in the name of justice. If killing was bad, it was bad for the Government to kill too… The Deputy Fiscal nodded his head and the executioner pulled the lever. Instantly the scaffold opened up and the man dropped. I got near and peeped down and saw the body hanging, still trembling – H.G. Dharmadasa, former Commissioner-General of Prisons

The death penalty is a popular and populist solution that is touted by politicians and governments as a quick-fix to tackle crime, as demonstrated by President Maithripala Sirisena’s attempts to resume executions in 2019, supposedly to eradicate the drug trade, and Sajith Premadasa’s recent calls for the death penalty for those convicted of the Easter attacks.

The death penalty is a popular and populist solution that is touted by politicians and governments as a quick-fix to tackle crime, as demonstrated by President Maithripala Sirisena’s attempts to resume executions in 2019, supposedly to eradicate the drug trade, and Sajith Premadasa’s recent calls for the death penalty for those convicted of the Easter attacks.

In Sri Lanka, the death penalty has been abolished and re-instated over centuries, beginning in the first century A.D. when it was abolished by King Amanda-gamani, who was followed by several abolitionists, such as King Voharika Tissa in third century. In the fourth century King Sirisanghabodhi is said to have secretly released those condemned to death and exhibited the corpses of those who died of natural causes as the bodies of the condemned he had supposedly executed. King Parakrama Bahu the Second did not implement the death penalty during his reign.

Since the early 1900s, attempts were made to abolish the death penalty, first in 1928 by D. S. Senanayake, and thereafter in 1936 and in 1955. The death penalty was suspended for three years in 1958 and re-introduced in 1959, after the assassination of Prime Minister Bandaranaike. Although since 1976 there is a de facto moratorium on executions, persons continue to be sentenced to death.

Myth 1: The death penalty is the antidote to the increase in crime

The tried and tested way of manufacturing public support for the death penalty is through false, unsubstantiated and hysterical statements aimed at fear-mongering about the supposed rise in crime. Aided by sensational media reports about gruesome acts of violence, such as constant reports of gun battles between the police and drug dealers, this creates the impression of a lawless and unsafe society, which can be made safe only by executing those that cause the crime and insecurity.

Leaving aside the fact that the death penalty does not result in substantive social change or make people safer because it does not address the root causes of crime, statistics show that the crime rate has declined.

As the Commission of Inquiry on Capital Punishment, also known as Morris Commission, which was established in 1958 to study whether the death penalty should be permanently abolished, stated in its report in 1959, ‘if the killings during the communal riots in 1956 and 1958 are excluded, the rate of murder and homicide in Ceylon has remained substantially stable between 1948 and 1958…’. Likewise, the Sri Lanka Police Grave Crimes Abstract  shows a decline in the crime rate as illustrated in table 1 of a few offences and total pending criminal cases.

shows a decline in the crime rate as illustrated in table 1 of a few offences and total pending criminal cases.

The misrepresentation of facts by the media, which is aimed at creating public support for the death penalty, is not new and was prevalent even in 1959. For instance, the Morris Commission highlighted, that it was ‘not only laymen who seemed to have been misled by the inaccuracy of the Press reporting. We found that judges, lawyers and police officers had had their views coloured in this fashion and several had based their evidence on inaccurate foundations of fact’.

The Commission goes on to caution that in such instances ‘the social wisdom of a suggested legislative step must be determined by reference to considerations other than the belief of the public in the wisdom of that step’. Hence, public opinion should not be the driver of legislative change in every instance.

Myth 2: The death penalty will enable the eradication of the drug trade

Another common myth that is used to justify the death penalty is its supposed effectiveness in eradicating the drug trade. The reality however is, once again, quite different. To curb drug trafficking, drugs have to be prevented from being trafficked into Sri Lanka, a task which requires information sharing between countries, including countries that are outside the South Asian region. Given that many countries do not share information with countries where prosecution for drug offences can result in a death sentence, the death penalty will restrict the ability to curb the inflow of drugs into the country.

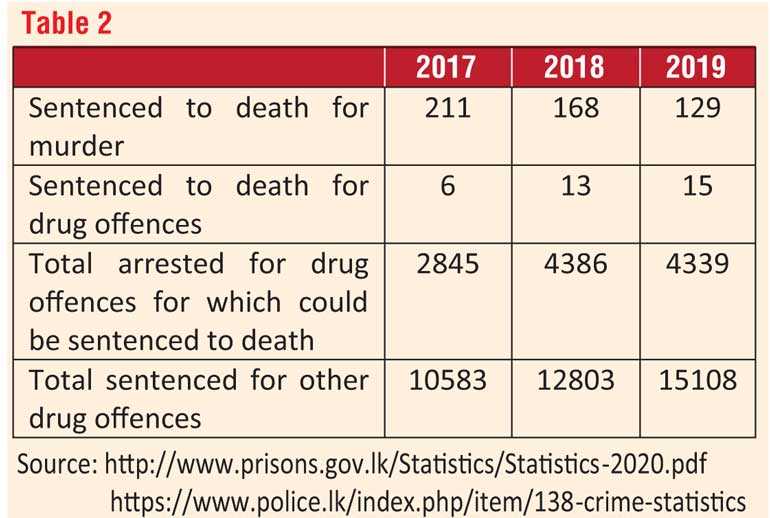

As table 2 illustrates, in 2019, 4339 were arrested for drug offences that attract the penalty of death, which includes possession of more than two gms of heroin and cocaine. However, in the same year, only fifteen persons were sentenced to death, while 15,108 persons were sentenced for drug offences that attract shorter sentences or fines. This indicates that the majority of persons arrested for drug offences possessed only small quantities of the drug, most likely for their personal use.

Hence, based on the statistics, it appears that those that are being imprisoned are mainly persons that use drugs and may be dependent on drugs, which should be dealt with via public health strategies and alternatives to imprisonment, such as community-based corrections. The imprisonment is most often for extended periods of time at considerable cost to the State and taxpayer, and has negligible impact on tackling the health and social impact of drugs. Thus, Sri Lanka’s drug policies and the manner in which drug offences are dealt with require review and reform.

Given the arrests of several law enforcement officers in the last few months, it can be assumed that those in positions of power and influence are part of the drug trade, suggesting that the militarised ‘war on drugs’ is a political tool, which distracts the public from systemic and structural dysfunctionalities. The rot is within our institutions, systems and society, which cannot be rectified through executions.

Myth 3: No person will be wrongfully sentenced to death

Myth 3: No person will be wrongfully sentenced to death

“Of all things that the State may take away from a man there is one thing if you take away you cannot only not return but you can never compensate him for, and that is his life” – Dr. Colvin R De Silva

The risk of miscarriage of justice was identified by the Morris Commission as one of the reasons the death penalty should be abolished. The Commission stated that, ‘On the evidence we have received, and from our reading of the literature from other countries…we cannot avoid the conclusion that there is a possibility in Ceylon that, if capital punishment is re-introduced, an innocent person may be executed. It cannot be dismissed as a remote possibility, and it is not one that can be ignored’.

This rings true even at present as illustrated by the wrongful arrests of two persons, including a 17-year-old for the rape and murder of five-year old Seya Sadewmi in 2015, and the extraction of a confession from one of them, allegedly through torture.

Furthermore, the fallibility of the criminal justice system has been pointed out, both by legal practitioners and the judiciary. For instance, in a Facebook post in 2018, President’s Counsel Saliya Pieris stated that, “A retired judge of the Court of Appeal [Sri Lanka], one time a trial judge told me how he decided to convict a man on a drug charge carrying the death sentence, but the night before the judgment, he pondered over the same and changed his mind. After acquitting the accused, the prosecuting counsel had come to him and told him that it was a good thing that he acquitted the accused because the police had confessed to him during the trial that their story was not true.”

Similarly, in February 2018 in Sujith Lal v Attorney General the Supreme Court rejected the appeal of the Attorney-General request a fresh trial after 20 years after the incident due to a ‘procedural irregularity in the Administration of Justice itself’ and upheld the decision of the Court of Appeal which set aside the conviction and sentence.

Many death row prisoners I met said that they could not afford a lawyer and were assigned a lawyer by the State. The prisoners felt their State-appointed counsels were young, inexperienced and didn’t mount a vigorous defence against the charges.

This is a concern that was highlighted by the Morris Commission even in 1959, when it stated that ‘the poor person accused of murder is unlikely to receive the legal assistance of a counsel experienced in the difficult task of conducting a defence in a murder trial: he may well find himself defended by a young counsel without any previous experience whatsoever of this type of work.’

Although the State provides a lawyer to appeal to the Court of Appeal, no free legal representation is provided to appeal to the Supreme Court, due to which many prisoners stated they had not appealed to the Supreme Court. It is such persons that would be executed if the death penalty were to be implemented.

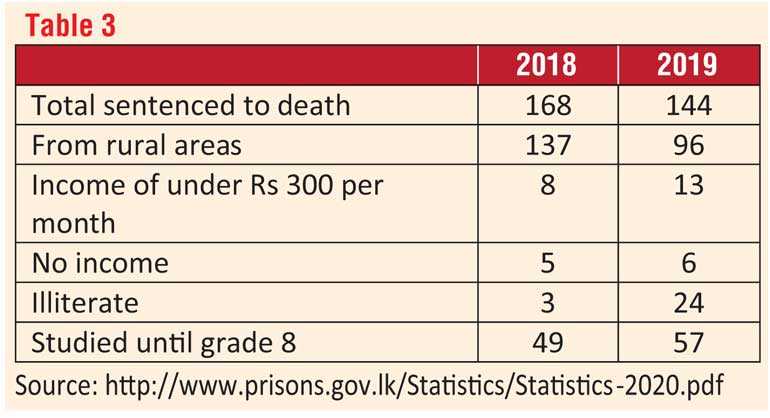

Table 3, which illustrates that the majority of persons on death row are from economically disadvantaged backgrounds and engaged in unskilled, informal sector occupations or low pay occupations in formal sector, corroborates the narratives of many prisoners about their inability to meet the costs of legal representation.

Myth 4: The death penalty will deter crime

Myth 4: The death penalty will deter crime

The most common argument of proponents of the death penalty, which is aimed at garnering public support, is that it will act as a deterrent, i.e. it will prevent people from committing crimes, and thereby make society safer. These arguments are flawed and in no way reflect reality.

The reality is reflected in events unfolding in India at the moment, where the execution of those responsible for the rape and murder of Nirbhaya in New Delhi, India in 2012, did not deter those that allegedly raped a young woman in Hathras and caused her death in September 2020.

The failure to address the root causes of crime, in this instance patriarchy, misogyny, discrimination and inequality, which are the root causes of violence against women, cannot be resolved by the death penalty. This was the finding of Morris Commission, which concluded there is no evidence to prove death penalty deters crime.

Moreover, the Morris Commission found that persons, ‘tend to be moved much more by immediate desires and immediate consequences than by remote possibilities of the difference between deferred and unlikely punishments’. Their finding is validated by the fact that the majority of persons on death row I met seem to have been convicted for crimes that were not premeditated but committed due to sudden provocation/heat of passion and do not have a history of criminality.

This is further substantiated by the statistics of the Department of Prisons, according to which, in 2018 and 2019, 84% and 83% of persons, respectively, who were sentenced to death, had no prior convictions.

(The writer is an Open Society Fellow. She was a Commissioner of the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka from October 2015 to March 2020.)

The reality of death row

The reality of death row

Death row prisoners live in cells and wards that often lack proper ventilation and natural light due to which many long-term prisoners suffer illnesses, with the most common being problems with eyesight.

In Welikada Prison for instance, death row prisoners inhabit severely overcrowded buildings that are dilapidated. Since most prisoners do not have access to sanitation facilities at night because their cells or wards are locked at night, they relieve themselves in plastic bags or buckets, which are hung precariously in overcrowded wards and cells.

Many prisoners said they felt depressed and had anxiety which interfered with their daily functioning. As death row prisoners are deemed ‘high risk’ they are locked inside their cells/wards the entire day and are allowed outside for only 30-60 minutes a day, which exacerbates their feelings of hopelessness and depression.

Prison officers, including a former Commissioner-General of Prisons, stated that death row prisoners often complained of physical ailments, which seemed to be a manifestation of their psychological condition, because as soon as they were transferred to hospital they declared they felt much better. This indicates that prisoners on death row in Sri Lanka experience the death row phenomenon, i.e. a physical and psychological condition triggered by the conditions on death row.

The families of many death row prisoners had fractured following their conviction, their partners had left them, and as a result their young children were placed in the care of their elderly parents or children’s homes. Stigmatisation and discrimination of the families of prisoners on death row is also not uncommon. For instance, some prisoners said that police reports that were issued to their children to submit to prospective employers stated the parent is on death row, which adversely impacted their employment opportunities.

The future: from moratorium to abolition

In addition to the reasons discussed in this article, the implementation of a cruel and inhuman punishment, such as the death penalty, diminishes our own humanity, and normalises and creates social acceptance of violence and cruelty.

Given that the reduction and prevention of crime requires creating a less violent and less cruel society in which humanity is prized, and violence is not valorised, the death penalty is an impediment to making society safer. The natural evolution for a civilised society, which currently has a moratorium on executions, would be to abolish the death penalty.