Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Thursday, 8 October 2020 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Perhaps the Sri Lankan leadership thinks a red line is unenforceable, or too expensive to enforce, and therefore stands deterred. Colombo may think it can eyeball it with Prime Minister Modi and Delhi over the ‘essential’ 13th Amendment. Where that deterrent capacity comes from, whether it will prove provocative or imaginary, is a subject for history. The regime’s constitutional Iron Curtain may descend on us as planned, but none can build a Great Wall of China all around a small island on democratic India’s doorstep, and maintain it in the midst of churning currents of contestation between America and China

“…instances of a myopic, extremist, resentful, and aggressive nationalism are on the rise… varieties of narrow and violent nationalism, xenophobia and contempt…” — Pope Francis, Encyclical ‘Fratelli tutti’ (‘All Brothers’) October 2020

COVID-19 is having a second surge (as the GMOA and Dr. Ravindra Ranan-Eliya and his team warned, interpreting the Johns Hopkins data with graphs), just as the Shanghai-based YICAI Research Institute placed Sri Lanka’s COVID-19 performance as the second best of 108 countries, next only to China, streets ahead of Vietnam, South Korea and New Zealand, and President Gotabaya Rajapaksa devoted eight paragraphs of his address to diligently inform the world’s leaders at the virtual global summit to mark the UN General Assembly’s 75th session, of his administration’s stellar performance, pointing out that “at a time when even the most powerful countries in the world were facing substantial challenges in the wake of COVID–19 pandemic, Sri Lanka was able to successfully face the challenge…we managed to contain its spread.”

COVID-19 is having a second surge (as the GMOA and Dr. Ravindra Ranan-Eliya and his team warned, interpreting the Johns Hopkins data with graphs), just as the Shanghai-based YICAI Research Institute placed Sri Lanka’s COVID-19 performance as the second best of 108 countries, next only to China, streets ahead of Vietnam, South Korea and New Zealand, and President Gotabaya Rajapaksa devoted eight paragraphs of his address to diligently inform the world’s leaders at the virtual global summit to mark the UN General Assembly’s 75th session, of his administration’s stellar performance, pointing out that “at a time when even the most powerful countries in the world were facing substantial challenges in the wake of COVID–19 pandemic, Sri Lanka was able to successfully face the challenge…we managed to contain its spread.”

When the Opposition Leader cautioned the Government in January about the coronavirus threat, he was mockingly dismissed. When he urged that the Parliamentary Election be held on schedule instead of much earlier, thereby allowing a concerted national effort to prevent a COVID-19 resurgence later this year, it was ignored. Unsatiated by a two-thirds majority, the perspicacious presidential preoccupation with the 20th Amendment and constitutional change—in the midst of a pandemic—diverted the Government from concentrating on preventing the predicted second surge. The citizenry and the economy suffer needlessly.

With the highbrow British journal Prospect naming K.K. Shailaja, the (Communist) Minister of Health of Kerala, as the world’s top thinker of 2020 in a list of 50 (this year’s competition emphasised ‘practical thinking’) for pre-empting COVID-19 in January when it had just manifested itself in Wuhan, and proceeding to bust it, it is surely in the interest of Sri Lanka, her next-door neighbour, to consult her.

|

|

|

The essential 13A

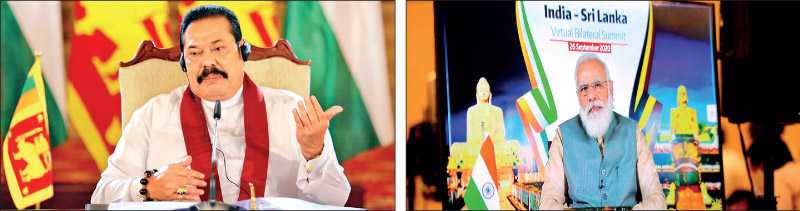

The Modi-Mahinda summit was important. Macroeconomic trouble looms (check the JP Morgan report) and Colombo needs the economic slack.

The Indian PM made an unambiguous statement about the Tamils and the 13th Amendment. The Sri Lankan side responded with slippery evasiveness but implied an interface by using the phrase ‘Constitutional provisions’. The Tamil issue and the 13th Amendment were contained in a distinct item, No 7, in the Joint Statement:

“7. Prime Minister Modi called on the Government of Sri Lanka to address the aspirations of the Tamil people for equality, justice, peace and respect within a united Sri Lanka, including by carrying forward the process of reconciliation with the implementation of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution of Sri Lanka. Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa expressed the confidence that Sri Lanka will work towards realising the expectations of all ethnic groups, including Tamils, by achieving reconciliation nurtured as per the mandate of the people of Sri Lanka and implementation of the Constitutional provisions.” (India-Sri Lanka Joint Statement on Virtual Bilateral Summit)

At the summit, Prime Minister Modi significantly added the word “essential” to his standard formulation. The official media release from the Indian side read: “He emphasised that implementation of the 13th Amendment to the Sri Lankan Constitution is essential for carrying forward the process of peace and reconciliation.”

After the Joint Statement, the Sri Lankan PM’s Office released its own statement omitting what the Indian PM said on the Tamils and the 13th Amendment, which the Sri Lankan side obviously signed-off on for inclusion in the Joint Statement.

Minister Keheliya Rambukwella attempted to spin the story at his first post-summit media briefing, and in his next one he grudgingly acknowledged the 13A reference in answer to a pointed question by the journalist, but downplayed and deflected Modi’s statement: “…it was an opinion…he expressed an opinion…”.

Prof. Charitha Herath, MP, and Viyathmaga member, explained on TV that in the making of a new Constitution the Government would take into account that which is good in the 13th Amendment and discard the bad.

State Minister Rear-Admiral Sarath Weerasekara, a Viyathmaga-Eliya luminary in whose charge the President judiciously placed the Provincial Council system, was more pointed:

“Provincial Councils is an internal matter which should be decided by the President of Sri Lanka and not by the leaders of other countries… India cannot interfere or intimidate that we should continue with the Provincial Councils… The 13th Amendment was introduced into our Constitution under the Indo-Lanka pact and according to which India had to fulfil several conditions and one of which was the disarming of the LTTE, which never took place. India could not accomplish it. Therefore, it is questionable as to what extent this Indo-Lanka Agreement is effective…”

(http://www.dailymirror.lk/breaking_news/Decision-on-PCs-up-to-President-not-heads-of-other-countries/ 108-196945)

Ven. Dr. Medagoda Abeytissa, a member of Eliya and of the Buddhist Advisory Council which President Gotabaya Rajapaksa convenes every month, pointedly queried: “How can there be a 13th Amendment in a brand-new constitution?”

It ain’t India

The sole substantive political point made by the Indian side at the level of the Prime Minister—who is a global player, not only a powerful national leader—is that of the Tamils and the 13th Amendment. By ignoring or brushing aside that single political point, which the Indian PM thought “essential”, Colombo makes clear that it does not take India’s political signalling—its messaging at the highest level—with the seriousness that is warranted.

Which external power has the most political influence over and within the current Sri Lankan regime? Whoever it is, it sure isn’t India. The paradox is that the island may be in India’s geopolitical sphere of influence but India’s political influence on the state is minimal, marginal, ineffective.

Is the potential cost of accommodating Prime Minister Modi’s ‘opinion’—or reminder—of what he regards as ‘essential’, greater than the potential cost of not doing so?

The 13th Amendment is the very core of the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord, a bilateral agreement between states—notwithstanding the governmental and/or constitutional changes.

Since the Accord and the amendment were the factors that pivoted India away from patronage of the Tamil cause to that of partnership with Colombo, can Sri Lanka risk a unilateral move on 13A triggering a potential, partial reverse effect—especially with slight signs of peaceful civic protest (the Thileepan shut-down) in the north and east?

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres has mentioned Sri Lanka critically in his report to the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva. India’s umbrella may be necessary for Sri Lanka in UN forums, for which the implementation of the 13th Amendment—a longstanding Sri Lankan pledge—may be a modest price to pay.

Washington-Delhi-Colombo

If President Trump wins, the external linkages and patronage the GR regime enjoys will attract the displeasure of the neoconservative anti-China ‘robust pushback’ strategists.

If former Vice-President Biden wins, the profile and practices of the GR regime will attract the critical gaze of a powerful resurgence of liberal-democratic internationalism.

In an essay in the prestigious Foreign Affairs, Joe Biden decries “the rapid advance of authoritarianism, nationalism, and illiberalism” and asserts his global perspective and project as prospective US President:

“The triumph of democracy and liberalism over fascism and autocracy created the free world. But this contest does not just define our past. It will define our future, as well.”

“…The United States will prioritise results by galvanising significant new country commitments in three areas: fighting corruption, defending against authoritarianism, and advancing human rights in their own nations and abroad.”

(https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-01-23/why-america-must-lead-again)

Candidate Biden alleges that “China is…extending its global reach, promoting its own political model…” (Ibid) President Gotabaya Rajapaksa asserts his “neutrality” as between the US, China and India, but the big boys go by the JFK dictum “never mind what he says, watch his hands”. Political power-projection and footprints leave distinctive ‘heat signatures’; state-reconfiguration reveals morphological correspondences.

‘Authoritarian’, ‘nationalist’, ‘illiberal’, ‘autocracy’, ‘China’s political model’: wouldn’t it be prudent for the Gotabaya Rajapaksa regime to stop checking all these Biden tick-boxes?

Whichever way the US election goes, it’s all the same to India. The US tilt to India began under a Republican President, George W Bush in 2004. Trump and Modi are friends, and the Trump administration is on the warpath with China. However, the American soft power affinity and romance with India as the world’s largest democracy, is far more a US Democrat passion dating back to Ambassador JK Galbraith. That dimension will take a quantum leap with a Harris Vice-Presidency.

India continues to attract and entrance Russia, a durable relationship which Moscow will not give up or jeopardise even for China. India’s active role in the SCO, the Commonwealth, the Nonaligned/G-77 and many other multilateral forums gives it diplomatic space that few big powers have.

President Mahinda Rajapaksa played the Indian card to offset Western pressure to stop the war. If President GR’s stand today on 13A had been President MR’s stand in 2008-2009, would we have been able to win the war, or would we have been interrupted—this time by the West—as we were in 1987?

Unlike the Geneva 2015 resolution which the Government can credibly dissociate itself from, the pledge to implement 13A comes not only from a Rajapaksa administration but was repeatedly conveyed by the ‘troika’ handling Indo-Lanka relations, which consisted of Secretary Defence Gotabaya Rajapaksa, Minister Basil Rajapaksa and Presidential Secretary Lalith Weeratunga. It was a pledge of three Rajapaksa brothers.

Doesn’t it trouble President Gotabaya Rajapaksa and his brothers, that having given their collective word in wartime to implement the 13th Amendment, he is coldly silent on the subject even in the company of Prime Minister Modi—and seems to be going back on it? Is President Gotabaya Rajapaksa reneging on our wartime promise to Delhi because he doesn’t think he needs India anymore?

The shared Rajapaksa assumption is that they were turfed-out in 2015 by an Indo-US tilt due to misapprehensions about a Rajapaksa gateway for China. If so, how would the USA and India view the return of the Rajapaksas and the constitutional ‘siloing’ of the regime at this time of intensifying strategic competition with China?

The most rudimentary geopolitical analysis would say that this island’s contiguous Northern and Eastern Provinces, with a fairly compact majority of Tamil speakers—an Indian language—and the Trincomalee harbour, constitute a natural buffer for India, to offset any expansion of Chinese influence in the Sinhala-majority two-thirds of this island located on India’s southern perimeter. Thus, the effective implementation of the 13th Amendment and the non-diminution of the Provincial Councils, is more than a mere opinion of Prime Minister Modi, but geo-strategically essential for India especially at a time of intensified competition with China.

The President’s new paradigm

When the leader of a big power, which is also an Indo-Pacific power and sees itself as a global player, makes a substantive political point at a bilateral summit—using the term ‘essential’—it is not an ‘opinion’, it is a signal, a message that the political point in question is something that matters to that big power. What sounds like an opinion could be a wake-up call about a red line.

Perhaps the Sri Lankan leadership thinks a red line is unenforceable, or too expensive to enforce, and therefore stands deterred. Colombo may think it can eyeball it with Prime Minister Modi and Delhi over the ‘essential’ 13th Amendment. Where that deterrent capacity comes from, whether it will prove provocative or imaginary, is a subject for history.

The regime’s constitutional Iron Curtain may descend on us as planned, but none can build a Great Wall of China all around a small island on democratic India’s doorstep, and maintain it in the midst of churning currents of contestation between America and China.

Meanwhile, for the first time in (almost) 60 years since Sri Lanka, then Ceylon, under the leadership of Madam Bandaranaike, was a founder-member of the Nonaligned Movement in Belgrade in 1961, a Sri Lankan Head of State addressed the United Nations General Assembly and omitted any reference whatsoever to Nonalignment and/or the Nonaligned Movement, the foundation of our identity and way of being in world affairs, and the global family we belong to.

It is also the first time in 64 years, since S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike addressed the UNGA in 1956, that a Sri Lankan leader addressing the UNGA, omitted any reference whatsoever to Palestine.

Addressing the virtual global summit of the UNGA to mark its 75th anniversary, President Rajapaksa completely avoided the terms Nonalignment/Nonaligned and declared instead that “Sri Lanka is committed to follow a neutral foreign policy with no affiliations to any particular country or power bloc”.

(http://www.dailynews.lk/2020/09/24/local/229612/president-gotabaya-rajapaksa%E2%80%99s-address-united-nations-general-assembly-unga)

He reiterated the shift in a conversation with new Ambassadors: “…In this context, Sri Lanka has chosen neutrality as its foreign policy...”

(http://www.ft.lk/news/President-tells-new-envoys-Sri-Lanka-s-foreign-policy-based-on-neutrality/56-706908)

Interviewed by P.K. Balachandran, Rear-Admiral Jayanath Colombage, Secretary to the Foreign Ministry, defined President GR’s policy of neutrality as NOT one of Nonalignment: “This is why the President is wanting Sri Lanka to be a neutral country, not a non-aligned country, but a neutral country…”

(https://southasianmonitor.net/en/column/we-must-be-mindful-not-to-be-a-strategic-concern-to-india)

The Nonaligned Movement was founded in the vortex of the Cold War and defined itself as opposing “bloc politics” and eschewing “affiliation with rival military blocs conceived in the Cold War context”.

For a small state like Sri Lanka, safety lies in numbers. The Nonaligned Movement is a grouping of 120 countries of which we were a founder-member and (later) a chairperson.

The 2020 GR regime’s mindset is a throwback to the 1980s JR regime’s mindset, critiqued as dangerously deluded folly and farce at the time by my father, Mervyn de Silva:

“The island’s ‘nodal position’ in the Indian Ocean and of course, Trincomalee, nourished the comforting conviction that Sri Lanka was the hub of the universe, and we ourselves a coveted prize that major external powers (external to the region) with their substantial global and regional interests, will be only too eager to pacify even at the risk of their demonstrably larger interests...”

(‘Sri Lanka’s Ethnic Problem’, Centre for Society & Religion, October 1984, republished in Crisis Commentaries: Selected Political Writings of Mervyn de Silva, ICES Colombo, 2001, p 65)

Today’s abandonment of nonalignment was pioneered in the 1980s. Its colossal fallacy was spotlighted by Mervyn de Silva, whose warnings proved prophetic in 1987.

“Cut away from its moorings, Sri Lankan foreign policy is adrift.” (Ibid, p67)

“It was not nonalignment that left us naked. It was the gradual rejection of all the basic premises of that traditional non-alignment, of which the cornerstone was the relationship with India, that left us naked to our enemies, real or fancied, internal or external.”

(Marga Institute lecture 1985, republished as ‘External Aspects of the Ethnic Issue’, Ibid, p72)

Nonalignment provides the broad, tested base, upon which policies of ‘multi-directionality’/‘omni-directionality’ which maximise flexibility, such as De Gaulle’s ‘tous azimuths’ and Primakov’s ‘multi-vector’, can be mounted. Swapping nonalignment for neutrality is beyond idiosyncratic; it is unilateral, arbitrary, neo-isolationist and solipsistic.

As with circulars, so with the making of foreign policy.