Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Thursday, 13 February 2020 00:16 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Every day, elephants are losing ground to the human tide

The Human Elephant Conflict (HEC) takes a heavy toll on wild elephants and human beings

Sri Lanka is said to have a wild elephant population of about 6,500, although exact numbers are not really available, in spite of some form of census that was carried out some years back. This approximately accounts for about 10% of the world’s Asian elephant populations, the rest being primarily in India, Thailand, Nepal, and Borneo. Sri Lanka may have over 18 National Parks, but the reality is that some 65% of these wild elephants are found outside these protected areas.

“With expanding human populations, natural habitats that are not designated as ‘protected’ are being converted to human habitats at an ever-increasing rate. Where elephants once ranged have sprung up crop fields; where they once bathed and peacefully drank is now an agricultural reservoir.

Every day, elephants are losing ground to the human tide. Their access to critical resources are blocked by human habitations and fences. When they come out to water or to feed in an open area, they are chased away. Trap guns, muzzle loaders, planks studded with nails left on trails, poison, all take their toll, killing and maiming elephants.” (Center for Conservation & Research).

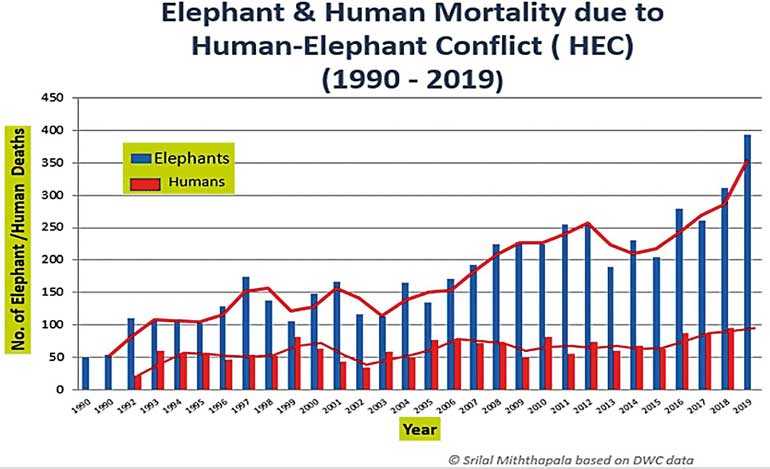

Hence the Human-Elephant Conflict (HEC) takes a heavy toll on wild elephants (over 360 deaths in 2019) and also human beings (over 100 human deaths recorded in 2019; Ref. Department of Wild Life Conservation).

HEC is probably the single biggest environmental issue that faces the country. It is a man-made, politically-fuelled conflict, a complex interaction between humans and wild elephants with detrimental consequences to both species.

Due to the high degree of intelligence of wild elephants, coupled with the expanding human population and unplanned development, finding solutions to the HEC is a very complex task. Piecemeal solutions will not do. Many Sri Lankan elephant researchers have developed good practical solutions to mitigate the issue. What is needed is a holistic, well-planned-out, all-encompassing strategy, taking into consideration all the available research by private researchers, to be implemented on a nation-wide scale, in a consistent and cohesive manner, without ad-hoc political interventions.

So what is wild elephant translocation?

Translocation of wild elephants means exactly that! Translocate: “Move from one place to another” (Oxford Dictionary)

So in reality, it is the ‘movement’ of a wild elephant from one area to another. This is normally undertaken by the Department of Wild Life Conservation (DWC) to move wild elephants who may be causing crop damage and harm to humans in one particular area, after tranquilisation, to another area which is possibly safer. However in reality, this is not the case, as will be discussed later, and often it ends up with ‘changing the pillow to get rid of a headache’.

How are wild elephant translocations done?

From the earlier definition, translocation seems a rather simple, straightforward process. However, this simple action becomes very much more complex, when one has to ‘move from one place to another’, a 4-5 ton intelligent wild animal who is stronger than a bulldozer, against its wishes!

This complex process requires quite a lot of planning, unlike some of the quick-fire translocations done by the DWC due to political pressure.

Firstly, a proper, well trained team has to be put together, with an experienced veterinary surgeon to undertake the tranquilisation. After assessing the area where the elephant is, the team will carefully track the elephant.

Choosing the site for tranquilisation is very important, because once tranquilised, the elephant has to be quickly ‘loaded’ on to the transportation vehicle, which should be a properly designed one. Hence the area chosen has to be free of large trees and other impediments, in a relatively open area. There should be adequate back-up staff and equipment such as bulldozers, backhoes, and strong tethering manila ropes. This whole procedure of getting the elephant into a suitable area for tranquilisation and transfer onto the transportation lorry may sometimes even take days, if done properly.

The veterinarian will then fire the dart loaded with tranquilising agent to the rump of the elephant. The moment the dart hits, the elephant will start to run, and it is imperative that the team follows it, and by blocking its exit, does not allow it to wander too far. In a few moments, if all goes well, the elephant is subdued, and will be in an inactive state. Contrary to some beliefs, dosage of the medication does not completely immobilise the elephant and it does not fall on down completely. The legs are noosed, and then with the aid of bulldozers, the elephant is ‘pulled’ and cajoled into moving closer to the truck. This is a rather cruel process, and often the elephant, although in a semi-drugged state, still puts up a fight, pulling at its shackles and even sometimes falling over.

In the meantime, the truck is carefully positioned with the rear door flap opened, and a ramp made of earth built around it, to facilitate the elephant’s movement into the truck. With some effort, if correctly executed, the elephant will be loaded onto the truck and secured. By this time, the tranquilising agent would have worn off, to some extent, and the elephant will be doused with water to cool it. This is a very traumatic experience for the animal. Some form of fodder will also be given, but most often the elephant would be in too much of an agitated state to eat.

Then comes the ride to its new home. Here again there should be careful consideration given to the distance of transportation. There have been instances in the past where animals have been transported long distances, causing great distress and even gruesome fatalities in transit. Once the release site is reached, the rear door of the truck is lowered, a ramp built and the elephant is carefully let loose. With the effects of the tranquilisation fully worn off by now, it will quickly run off into the surrounding area.

Why is it translocation done, and what are the repercussions?

It is an attempt to get rid of the problem created by a wild elephant which may be crop-raiding and causing danger to humans. But as indicated earlier, it really does not solve the problem, and may even aggravate it at times.

Elephants have been found to have their own home ranges. Male elephants are solitary by nature, and constitute almost the entirety of the so-called ‘problem elephants’. They have a larger range than females and herds. These home ranges are very familiar to them, and are mapped out in their brains. So if they are forcibly relocated, they always try to find their way back to their original home grounds.

HEC is probably the single biggest environmental issue that faces the country. It is a man-made, politically-fuelled conflict, a complex interaction between humans and wild elephants with detrimental consequences to both species. Piecemeal solutions will not do. Many Sri Lankan elephant researchers have developed good practical solutions to mitigate the issue. What is needed is a holistic, well-planned-out, all-encompassing strategy, taking into consideration all the available research by private researchers, to be implemented on a nation-wide scale, in a consistent and cohesive manner, without ad-hoc political interventions

There is spectacular recorded evidence by Dr Prithiviraj Fernando, Sri Lanka’s foremost wild elephant researcher and expert, of elephants who have been translocated, even some hundreds of kilometres away from their home range, eventually finding their way back to their original home areas. (Ref. Centre for Conservation and Research). The sad part is that in the translocated elephant’s ‘journey’ in finding its way back to familiar territory, it often has to pass through unfamiliar villages and built-up areas. There are altercations with humans, some with disastrous consequences of bullet wounds and other injuries, further angering the elephant. Several die during this attempt to relocate back to their home range.

At the other end of the spectrum, the few translocated elephants who do not move back to their familiar territories, manifest aggressive and abnormal behaviour, possibly due to the extreme stress and physio-psychological effects that they underwent. (Chiyo PI, Archie EA, Lee PC, Moss CJ, Alberts SC, 2011).

In the worst case, there are situations where translocations go horribly wrong, resulting in fatalities as was the case when the magnificent tusker from the Galgamuwa area was hurriedly translocated by the DWC on the orders of a Minister, with disastrous consequences.

Hence, it is more than evident from hard scientific research and facts, that translocation does not solve the root cause, and may in fact aggravate the issue, or at the most, translocate the problem to another area.

Then why do translocations? Are they ethical?

As explained earlier, haphazard and unplanned development has reduced and fragmented the land available for good elephant habitat. Hence, we have encroached into lands that wild elephants have used for centuries. Due to their strong home ranging behaviour, elephants will not adapt and move away. They continue to stake their claim to ‘their lands’, and thus begins the conflict with man.

A good case in point is the Uda Walawe National Park. It was established in 1972 as a catchment area for the reservoir, and it harboured a large population of wild elephants. A few years after 1972, the Government, in its infinite wisdom, set up the main sugar cane research facility at Uda Walawe, and encouraged farmers to cultivate sugar cane right across from the Park, separated only by the B427 Thanamallwila Road. Sugar cane, to an elephant, is like showing candy to a child. In next to no time, the elephants were raiding the plantations just outside their ‘designated home’. The DWC had to spend millions of rupees in setting up not one, but two electric fences to keep the elephants away.

There are situations where translocations go horribly wrong

To a great extent, wild elephants will give humans a wide berth. But there are some males – who are always solitary – who get used to crop-raiding and finding easy and tastier sources of food in plantations. Herds do not resort to such raids, because most often they have juveniles in the herd. So it is not surprising to find that a few of the adult males get used to this behaviour, and no doubt become a nuisance, and in some cases a danger as well. And it is a fact that something has to be done to protect the humans.

However, the root cause is NOT the elephant, but unplanned development and land encroachment. So on an ethical basis, there is no case whatsoever in concluding that a marauding elephant is primarily at fault.

A good example is the infamous Rambo, of Uda Walawe fame, who stays on the bund of the reservoir, and solicits tit bits from passers-by. There was some ideas mooted to translocate this elephant some time ago, but thankfully that idea was shelved. This is an even more interesting ethical issue. This elephant is WITHIN the confines of the National Park, standing placidly behind the electric fence, and not harming anyone. If anyone should be prosecuted and found fault with, it should be the people who stop and feed the animal. In any event, I am of the opinion that Rambo is so famous that he has done more to promote Sri Lanka and its wildlife than any high-level paid promotional campaign could have achieved.

Therefore, I believe that Rambo’s value is immense, but unfortunately goes unnoticed. Of late, for reasons yet unknown, Rambo has moved away from the fence, and now spends his time back within the confines of the Park.

Hence, translocating an elephant does not work, both on scientifically proven grounds, or on an ethical basis. However, in extreme cases, when all other efforts prove unsuccessful, after careful assessment, a rare translocation may be required.

If not translocation, then what?

At the outset, the root cause for translocations to be considered is the HEC, which has to be addressed. As indicated earlier, this has to be a national level, well-coordinated, planned effort based on proper scientific research findings, and based on proper data.

Unfortunately in the current context, hoping to see something like this happen seems to be a pipe dream.

In the meantime, there are some initiatives that could be implemented in the short-term. Some researchers have currently conducted case studies on enclosing entire villages by an electric fence in the night, which is proving to be quite effective. As elephants raid mostly in the night, during the day, the village will have one or more access points to move out, which need to be closed so the electric circuit is re-established at night. Hence in problem areas, such electrified enclosures could be installed. Of course, the ideal situation would be to remove the village settlements away, if they have been put up illegally. This of course has major political implications, and will therefore not happen.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is quite evident that translocation of wild elephants to mitigate crop-raiding is not a viable solution at all.

Dr Prithiviraj Fernando et al. sum the situation lucidly in their research paper:

“We conclude that problem-elephant translocation causes intensification and broader propagation of HEC and increased elephant mortality, and hence defeats both HEC mitigation and elephant conservation goals. The driver of translocation is public and political pressure. Capturing and translocating an elephant from the vicinity of major HEC incidents may defuse tension, and hence be of relevance in particular contexts. However we found that even if the original problem is solved by translocation, the same or more likely worse is created at another location.” (Ref: Problem-Elephant Translocation: Translocating the Problem and the Elephant? Prithiviraj Fernando, Peter Leimgruber, Tharaka Prasad, and Jennifer Pastorini)

Translocating an elephant is a complex process that requires quite a lot of planning

Rambo’s value is immense but unfortunately goes unnoticed