Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Wednesday, 10 July 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Each year, usually in November, the Finance Minister presents the National Budget on behalf of the Government. Over several weeks that follow, the budget is debated in Parliament and put to the vote. If it is not approved, the Government falls. If approved by a simple majority, it goes into effect for the following January-December financial year. Thereafter, the Parliament that approved it, both Government and Opposition, is responsible for its  implementation.

implementation.

The Budget presentation is met with excitement. There is speculation preceding it about what it will contain and who will benefit or suffer, immediately followed by a social whirl in Colombo. Leading professional and academic organisations arrange several seminars on its implications and impact. Some events are preceded by sumptuous breakfasts, others followed by delightful cocktails. For a week or two, newspapers report on all these events. They also carry articles on the Budget written by eminent scholars and economists.

Thereafter, everyone loses interest, other issues take over media space, the country adjusts to the new tax regime, finding more innovative ways to beat it, and it is business as usual until the next budget a year later. Whether budget proposals are implemented and revenue, expenditure and borrowings stay within budgeted targets remain of interest only to the Treasury, Central Bank, Parliamentary sub-committees that oversee public finances and a few academics and research institutions that take the trouble to monitor budgetary performance throughout the year.

However, implementation or non-implementation of budget proposals and budgetary performance affect our lives in different ways. It therefore befits us to understand the Budget and to discuss and critique it if we expect better budgetary performance. It is hoped that this article will encourage such efforts.

What is a National Budget?

A National Budget is an annual financial plan that specifies:

Sri Lanka last had a budgetary surplus in 1955! Budgets for the past 64 years have focused on how to meet a deficit.

Government Expenditure falls into two broad categories:

Government Revenue is mainly raised through taxes, specifically two types:

Sri Lanka’s Budget Deficit has been financed by two types of borrowings:

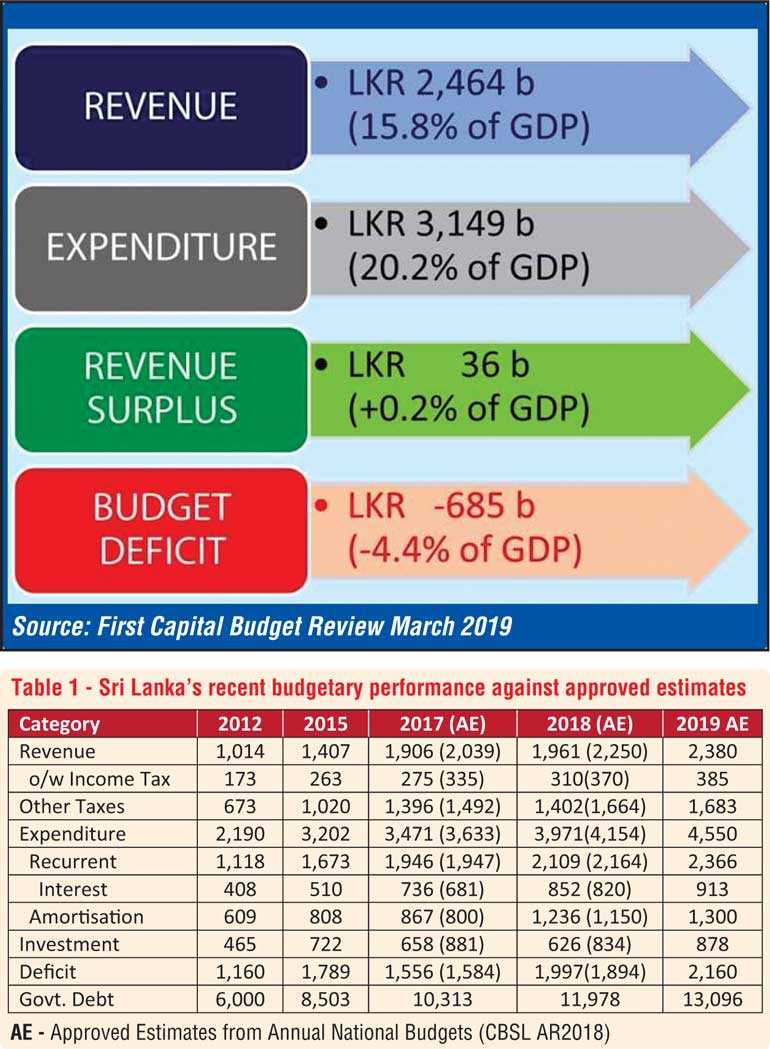

Sri Lanka’s recent budgetary performance

As Table 1 shows, recent budgetary performance has not met targets.

Clearly, Sri Lanka has lived beyond her means and got into a vicious borrowing cycle to finance debt repayments. This is not sustainable. There is no free lunch.

Why is the National Budget important?

Although merely a financial plan, the Budget plays an important role through the messages it conveys. In particular, it should

Who is responsible for preparing and implementing the Budget?

The Budget is a collective responsibility.

Problems with the process

Sri Lanka has around 1,300 Government institutions and (at the time the budget was presented) 29 Cabinet Ministers covering overlapping and inconsistent subjects. For example, Social Empowerment vs. Social Progress and Resettlement vs. Resettlement of Protracted Displaced Persons! Cabinet Ministers existed for Northern Province, Western, Wayamba, Southern, Dry Zone and Kandy Development, but not for other geographical regions. Consequently, Government institutions are tossed about like tennis balls among these 29 Cabinet Ministers, three Non-Cabinet Ministers, 17 State Ministers and seven Deputy Ministers, with no concern for systems, processes, continuity or institutional memory. In this confusion, it is virtually impossible to ensure transparency and accountability to reduce wasteful expenditure. For example, there is no precise record of vehicles used by the Government.

Appointing a COPF is an excellent concept to place responsibility for implementation on Parliament, both Government and Opposition. However, COPF can only be effective if its members understand basic economics, accounting and finance to discharge their responsibility. In fact, all MPs require basic Economics to be able to contribute substance to Parliamentary debates on budgetary matters. Based on this author’s limited first-hand experience, this is far from the reality.

The proposed Budget office to support COPF is yet to be set up. Currently, Treasury officials do not have faith in the COPF’s commitment to their task and COPF members do not trust the Treasury.

What would help?

Stakeholders must limit Government to a reasonable number of ministries in non-overlapping policy areas. Australia (population 25 million) has 17 Cabinet Ministers and India (population 1,358 million) has 27 Cabinet Ministers.

Stakeholders must hold the Government accountable for zero tolerance of wasteful expenditure and widening the tax net. This will help reduce the deficit.

The Secretary General of Parliament or Speaker should arrange a basic economics program for all interested MPs, including COPF members, using resource persons from the Central Bank and Treasury. This will also lead to greater trust between the COPF and Treasury.

Media, civil society, business and political organisations can encourage better budgetary performance through greater understanding and constructive criticism of the monitoring systems and processes currently in place, or lack thereof.

The capacity to improve budgetary performance needs tremendous commitment to human resources, institutions, systems and processes at all levels of Government, as well as the citizenry.

(The author retired as Assistant Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka in October 2007.)