Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Friday, 20 October 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Reforms in political parties are necessary in the process of democratisation of any country, however on the condition that those are progressive and democratic, and not regressive or authoritarian. In the history of political parties in Sri Lanka there have been many splits, famously in the Left parties, and formation of new parties, but very few attempts at reforming parties within and in the democratic direction.

Reforms in political parties are necessary in the process of democratisation of any country, however on the condition that those are progressive and democratic, and not regressive or authoritarian. In the history of political parties in Sri Lanka there have been many splits, famously in the Left parties, and formation of new parties, but very few attempts at reforming parties within and in the democratic direction.

The political party system is not something adequately studied in Sri Lanka especially in recent times. When Howard Wriggins wrote his nearly 500 page book, ‘Ceylon: Dilemmas of a New Nation’ (1960), he had a chapter on political parties and noted the importance of the formation of the SLFP in 1951, breaking away from the UNP, for the evolution of a competitive and possibly two party system.

More comprehensive and a focused study came from Calvin A. Woodward in 1969 titled ‘The Growth of a Party System in Ceylon,’ with whom I associated very closely at the University of New Brunswick. James Jupp also focused on the political party system, in a critical manner, in his ‘Sri Lanka: Third World Democracy’ in 1978. K. M. De Silva, as a foremost modern historian, and A. J. Wilson, as a leading political scientist, also paid attention on the subject in many of their books.

Wiswa Warnapala has two books on the SLFP, one after the other, ‘Sri Lanka Freedom Party and the Political Change in 1956’ in 2004, and ‘Sri Lanka Freedom Party: A Political Profile’ in 2005. He himself was a SLFP member/leader. There is no such a profile or a book to my knowledge on the UNP, by an outsider or an insider. The Federal Party (FP) was fairly covered in A. J. Wilson’s ‘Sri Lankan Nationalism’ (2000).

The Left movement or rather the LSSP was studied by G. J. Lerski in his ‘Origins of Trotskyism in Ceylon’ (1968), followed by Ranjith Amarasinghe in his ‘Revolutionary Idealism and Parliamentary Politics: A Study of Trotskyism in Sri Lanka’ (1998). All above are just a memory outline and not a complete catalogue.

In the whole vortex of political ideologies, party formations, splits and party rivalries or competitions, what is the general position of the SLFP? Has it played a significant role in the political and socio-economic development in the country?

All academics and analysts have agreed that the formation of the SLFP in 1951 was a significant landmark in the democratic development in the country as it supplied an alternative to the UNP. It contributed to the evolution of a two-main-party system. Unfortunately, the Left was not in a position to supply that alternative due to many ideological and bickering splits.

What was the main reason for its formation? The main reason given was that the UNP was not representing the majority of rural masses. The UNP was considered an urban and an elitist party, of course with a rural base. This was the genesis of the SLFP’s Pancha Maha Balavegaya (great five forces), whether that is valid in the same way today or not. The Marxists gave another interpretation to this difference, naming the UNP as representing the ‘comprador bourgeoise’ and the SLFP, the ‘national bourgeoise.’ The ‘national’ label to the SLFP had a validity in other respects as well. It wanted to break away from all vestiges of colonialism or neo-colonialism. Whether right or wrong, the policies followed by the SLFP governments had this angle until recently. On the other hand, there is much reason today to consider the world situation not merely as neo-colonialism but globalisation. Even China is promoting a form of globalisation.

There was no strict ideology for the SLFP, until of course the ‘Mahinda Chinthana’ invention, as it appeared a pragmatic party with nationalist orientation. S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike was a declared ‘rationalist’ at the beginning. He embraced Buddhism and then he embraced nationalism while in his initial writings cautioning about extreme nationalism. He had a vision, as he said, to unite the Sinhalese first and then unite the Tamils and the Muslims for a long journey for national rejuvenation. But he blundered in his language policy and many others and the vision of uniting all communities got lost, during his time and thereafter.

Whether that vision can be implemented or resurrected under the new party reforms and changes is the question now. The present leaders might tread in that direction cautiously, given the sensitivities attached. The President’s recent visit to Jaffna and Governor Reginald Cooray’s initiatives give the impression that the Government and the party are in that direction.

There had been several splits within the SLFP in the past. In 1964, C. P. de Silva left the party and brought down  the SLFP government and then joined the UNP. In 1984, Chandrika Kumaratunga left the party and joined her husband’s Sri Lanka Mahajana Party, but returned back to the fold in 1991. Even Anura Bandaranaike left the party in 1993 and joined the UNP. Most of the splits those days were going in the UNP direction.

the SLFP government and then joined the UNP. In 1984, Chandrika Kumaratunga left the party and joined her husband’s Sri Lanka Mahajana Party, but returned back to the fold in 1991. Even Anura Bandaranaike left the party in 1993 and joined the UNP. Most of the splits those days were going in the UNP direction.

However, during Mahinda Rajapaksa’s time, many people broke away from the UNP and joined the SLFP. He was extremely smart in that sense. Some people argued that the new comers got more prominence and control than the traditional SLFP members. This is something that gave extremely an upper hand to MR and another accusation was that the SLFP became more of a family and a group party than a membership organisation. CBK was sidelined or she distanced herself from the party. Corruption apparently underlined these developments during particularly the second term of Mahinda Rajapaksa. Under his yoke, the traditional SLFP leaders were quite meek and ‘obedient’. That is apparently what he expected and the present author had many occasions to observe this dynamic.

Then how could we explain the last minute break (after eating hoppers together!) of a small group of people with Maithripala Sirisena in November 2014 and contesting the presidential elections backed by the UNP and the TNA? Was it like C.P. de Silva’s break in 1964? It was possible that the split going that way, if not for MR’s handing over the SLFP leadership to Sirisena in 2005. Then why did he do that? There can be three or four explanations. (1) MR was so confident in winning the election, but got completely demoralised after the defeat. (2) He was just following the party constitution, although uncharacteristic of him. (3) He rationally realised that otherwise, the party might rebel against him. (4) Sirisena’s pressure was so overwhelming, he didn’t have any other option.

Whatever the reason, handing over the party was a significant landmark not only in the SLFP history, but also the party system in the country. Because it has opened up the opportunity to reorganise the SLFP as a modern and a membership based party. This was not the case before, and particularly under MR. He excessively believed in personal Charisma mixed with voodoo type practices and encouraged faithful followers, but not policy based members. The best explanation for the downfall of such personalities or regimes come from none other than the Chinese President, Xi Jinping:

“In recent years, long-pent-up problems in some countries have led to resentment among the people, unrest in society and the downfall of governments, with corruption being a major culprit. Facts prove that if corruption is allowed to spread, it will eventually lead to the destruction of a party and the fall of government.”

This is of course said in November 2012 in respect of countries like Thailand, the Philippines and South Korea (‘The Governance of China,’ p. 17). However, it equally applies to Sri Lanka, not only to the last government, but also to the present one, if the dubious corruption trends continue.

An agenda for party reforms were set in motion first in September 2015 at the 64th anniversary of the SLFP. The main guiding personality was Maithripala Sirisena. He had almost 50 years of experience in the party, beginning at the grassroots level. Having been the general secretary of the party between 2001 and 2014, for 13 years, he was quite familiar with the party branches and activists all over the country. He was supported by several old and young leaders, Duminda Dissanayake among the latter as the General Secretary.

In addressing the party members at the conference, he was justifying the National Unity Government with the UNP on the basis of national urgency, stability and national reforms. He was of the opinion that the SLFP has weakened through personality cults. Therefore, he said, “I offer the hands of brotherhood to all of you to join with me to build a strong Sri Lanka Freedom Party.” Of course, building a strong party is not necessarily of building a reformed party. But regarding reforms, the following was what he categorically said:

“Therefore, as the SLFP, all of you have the responsibility to reform the party completely within the coming period after the 64th anniversary. This party should be built as the main populist political party which is accepted by Sinhala, Tamil, Muslim, Malay, Burgher, Buddhist, Catholic, Hindu and Islam. Everybody should work for that end with utmost commitment.”

Other points he outlined were ending violence, including post-election violence, elimination of hate politics and giving priority to policies before personalities. He also said, “I am a person who is on a slow journey. But I am not ready to turn back in that slow journey.”

Whatever his efforts, unity within the party, within the parliamentary group or the UPFA was difficult to maintain. Perhaps it was not necessary. First, the Joint Opposition was formed, the former President as the inspirer, and some other parties in the UPFA also taking a leading role. That was in late 2015. The main reasons appeared to be the policy differences or antagonisms with the UNP. Then a new party, the Sri Lanka People’s Front (SLPF), was formed in November 2016 as a counter organisation to the SLFP. Some of the reasons were related to the corruption charges levelled against those who were close to the former President, and side lining of them and some others within the SLFP. The corruption charges were considered political victimisation.

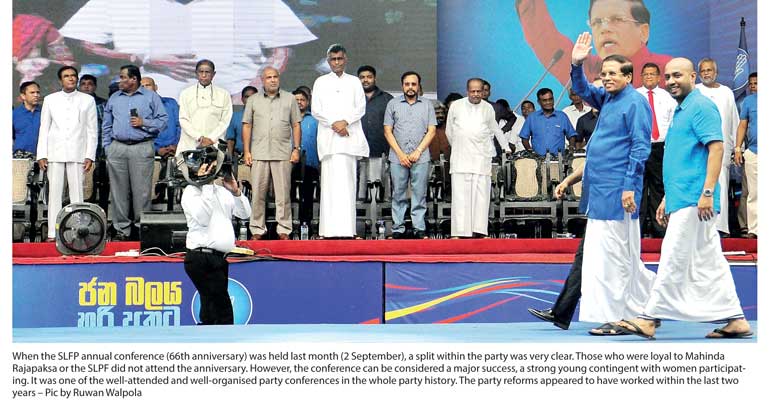

When the SLFP annual conference (66th anniversary) was held last month (2 September), a split within the party was very clear. Those who were loyal to Mahinda Rajapaksa or the SLPF did not attend the anniversary. However, the conference can be considered a major success, a strong young contingent with women participating. It was one of the well-attended and well-organised party conferences in the whole party history. The party reforms appeared to have worked within the last two years.

The 66th anniversary conference deserves separate attention some other time in discussing party politics and the SLFP in Sri Lanka. However, the emergence of the SLPF cannot also be underestimated, considering MR’s still remaining popularity, perhaps money and networking.

The policy line that the President has taken in his speech at the conference was against ‘Corruption, Fraud, Irregularities and Waste.’ He reverberated the Sinhala words for them ‘Dushanaya, Wanchawa, Akramikatha and Nasthiya.’ He might not be a shrewd social networker like MR, but he is one of the best political speakers perhaps after S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike. Those slogans can still be an election winning platform for the SLFP, among other things, although that was the same platform that MS won the presidency in January 2015. Yet, those may have a cutting edge against both the SLPF personalities and the UNP, while some of the tainted characters are still with the SLFP.

It appears that Sri Lanka is moving towards a three-party competitive system in most of the electoral constituencies in the near future. While the SLFP is still in the National Unity Government with the UNP, and has very closely worked in addressing some of the key national and international issues, there are areas where there are failures particularly in economic policy and performance. On some of these socio-economic maters, the traditional differences between the UNP and the SLFP have surfaced again and again.

Therefore, if the SLFP is not to leave the Government and disprove what MR has predicted in breaking the National Unity Government this year, the UNP may have to listen more and more to the SLFP in addressing economic development issues and socio-economic grievances of the people. In analysing the history, policies, leaders and organisations of the two parties, one may observe that the SLFP is closer to the people and their aspirations than the UNP.