Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Saturday, 26 September 2020 00:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

SWRD Bandaranaike’s enemies, both within the Sinhala community and the Tamil community, were those from the upper class he came from, the English educated brown sahibs who probably were more British than the British. They were his friends until he decided to espouse the cause of the majority in the country, who did not wish for one set of colonialists to be replaced by another

Two issues had rankled Buddharakkitha. One was the Prime Minister’s refusal to hand over a lucrative shipping contract to a company named Colombo Shipping Lines that was co-founded by him in the name of his associate HP Jayawardena to import rice from Burma (Myanmar) and Thailand. The second was over a sugar manufacturing licence to start a sugar factory – D.B.S. Jeyaraj (30 September 2019 – The Prime Minister is dead! How and why S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike was assassinated 60 years ago)

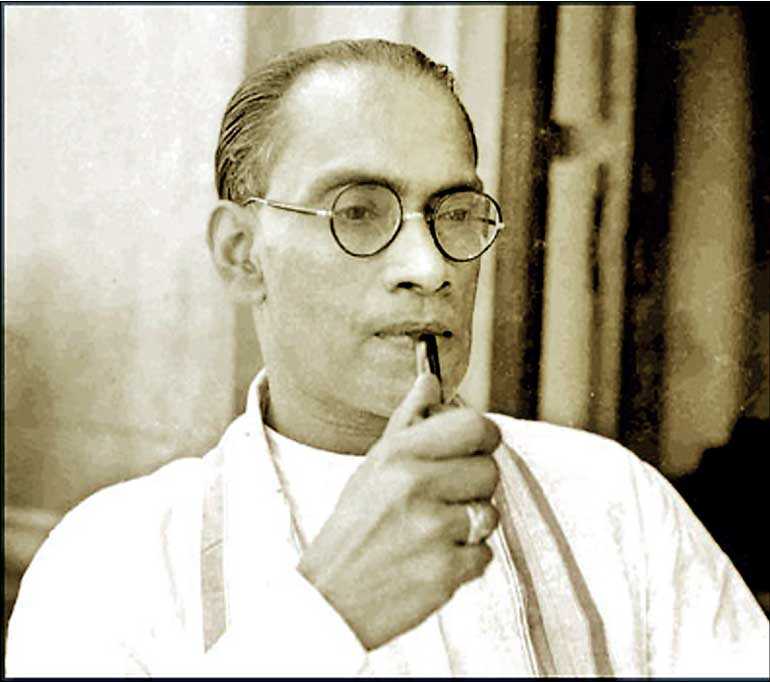

Today, 26 September 2020, is the 61st death anniversary of Sri Lanka’s fourth Prime Minister S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike. A gun and a bullet ended his life, but what really killed him was the unmitigated avarice of a person who was the opposite and a disgrace to the message of Buddha. That person was the Chief incumbent of the Kelaniya Temple, a businessman who knew no ethics nor morality, Mapitigama Buddharakkitha. It is not befitting to call this person a Buddhist Monk as he was anything but a follower of Buddha or the Buddha Dhamma.

The man who fired the gun and emptied bullets into the Prime Minister’s body, Talduwe Somarama was not of sound mind and easily brainwashed, and he was, to the extent of killing the Prime Minister “to save Sinhala Buddhism”, by Buddharakkitha.

Sordid politics and unmitigated avarice has not abated in Sri Lanka, and neither has the misuse of Buddhist robes by persons who are anything but Buddhist. Sri Lanka has not learnt from that fateful episode on 25 September 1959 when a wearer of a Buddhist robe emptied bullets into the country’s Prime Minister who was paying obeisance to that person in Buddhist robes.

Politics is equally or even more sordid than then when one reads about the mudslinging going on at the enquiry into the Easter bombings in 2019. It is so when one reads about the life and times of the Yahapalanaya government of 2015 and the tussle between the then President and Prime Minister of the country. It is when one hears and reads about the calibre of politicians we have and have had, who have traded the country’s principles and wealth and dignity for monetary gain. There is plenty more to write about, but that will require several volumes of books.

Buddharakkitha was the driving force behind the ‘Eksath Bhikku Peramuna’ or the United Bhikku Front. He has been described as a virtual kingmaker at that time. Later, he attributed Bandaranaike’s failure to aggressively pursue the nationalist reforms as the sole motive to assassinate him. But it was revealed that the real motive for the assassination came as a result of the Prime Minister’s refusal to award business deals, in particular, a government contract for the construction of a sugar factory and government concessions for a shipping company he planned to set up. Talduwe Somarama, “a misguided man wearing a robe” so described by the dying Prime Minister himself, fired the bullets that ended Bandaranaike’s life on 26 September 1959.

D.B.S. Jeyaraj writing on the 60th death anniversary of S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike (The Prime Minister is dead! How and why S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike was assassinated 60 years ago), lays bare the poisonous and unstable environment in the country in 1959.

He writes about the vertical and horizontal tensions of the country where on the one hand there was overt inter-ethnic strife on the grounds of language while there was on the other hand covert tussles on the basis of class and ideology.

He says the ethnic dimension was exaggerated or distorted to divert focus away from or under-emphasise the class dimension. Jeyaraj writes to say “Bandaranaike himself had begun acting against his class interests. The nationalisation of bus transport, insurance companies and Colombo harbour, etc. were some of the socialist measures enacted by the SWRDB government. Since most of the vested interests affected by these measures were UNP or pro-UNP it did not matter much to the regime. But the Paddy Lands Act pushed through mainly due to efforts of Philip Gunewardena regarded as the “Father of Marxism” in the country had different repercussions. The act provided greater rights and concessions to the long suffering tenant cultivators. There was however a large segment of semi-feudal, land-owning classes supportive of the SLFP also. The Paddy Lands act hit these sections and there was resentment”.

The exaggerated ethnic dimension and the aftermath of the class war had resulted in the Government’s Parliamentary strength being just 47 out of 101 by 11 June 1959, and Bandaranaike was in fact leading a minority government when he died on 26 September 1959.

The incident on 25 September may not have been the first to get rid of the man who was a victim of the class battles and avarice and at the same time the one person who was in the way of a total victory by forces driven by rightist ideology and unmitigated avarice. What had happened on 25 August 1959, when Minister C.P. De Silva had drunk a glass of milk suspected to have contained a vegetable-derived poisonous substance in the boardroom where the cabinet met, may have been intended for the Prime Minister himself. C.P. De Silva’s condition had proven so critical that he had to be flown to London for medical treatment.

Jeyaraj writes about the “purge of leftists and assertion of rightists to shackle S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike. The intention was to transform him into a puppet but the aristocratic Oxonian though beleaguered would not give in totally to Buddharakkitha’s diktat. Irritated by this the “kingmaker” priest now decided to remove Bandaranaike altogether. The flashpoint causing this change of mind was not race, class or ideology. It was sordid commerce”.

He goes on to note two issues that had rankled Buddharakkitha. One was the Prime Minister’s refusal to hand over a lucrative shipping contract to a company named Colombo Shipping Lines that was co-founded by him in the name of his associate HP Jayawardena to import rice from Burma (Myanmar) and Thailand. The second was over a sugar manufacturing licence to start a sugar factory. Buddharakkitha was a very rich businessman and he used whatever means at his disposal to acquire power in order to further his business interests. The wealth of the Kelaniya temple gave him the foundation to build his business empire. He did not tolerate anyone who stood in his way, and even a Prime Minister was not spared.

Had he been a Buddhist, acted as one and lived as one, heeding the Buddha’s message of love and impermanence, and the consequences of avarice, he wouldn’t have suffered the ignominy of dying as an inmate of the Welikada prison in 1967 serving a life sentence for the crime he had committed.

It is interesting to note Jeyaraj’s comment about the exaggeration of ethnic issue as a contributor to the tensions that existed in the country in 1959. In this context, it is opportune on this sad anniversary to note the following.

Firstly, there had never been a question of implementing the so-called Sinhala only policy ‘in 24 hours’ as widely and successfully marketed by opportunists. As Bandaranaike said, no law had been needed to make English the language of the country, therefore no law was needed to change it. It was to be a limited and a gradual process.

Secondly, there was clear articulation on a transition period for public servants to acquire a working knowledge of Sinhala, by December 1960, but this specific mention related only to the Supreme Court.

Bandaranaike said, in presenting the Bill, “It is our intention, as far as possible, to make that change wherever possible but if, in the course of our proceedings in implementation, we find on sufficient grounds and data that the changeover just cannot reasonably be made during that time, we will not hesitate to come before this House and the country for passing the necessary amendments to the Bill”.

Thirdly, at the time the bill was passed, there were no specific provisions in it in regard to the medium of instruction in schools. Bandaranaike did recognise that the medium of instruction should be the mother tongue of the student, rather than the official language of the country.

Fourthly, the Bill did not specify time frames for a changeover to the official language in other areas like local authorities. In the public service, the stated intention was to provide an adequate knowledge of Sinhala to all public servants so that, as contemplated, public service should be conducted in the official language within 10 years, meaning by December 1967. The reasonable use of the Tamil language in predominantly Tamil areas would have required Sinhala public servants working in those areas to acquire a working knowledge of Tamil.

It is well to remember that less than 5% of the population of the country were literate in English when Ceylon gained independence in 1948, and all Courts, Police stations, government departments carried out their official work in English. An overwhelming population of Sinhala and Tamil citizens, in excess of 95% of the population, lived as foreigners in their own country, unable to enjoy their rights as citizens of their newly independent country.

It is in this backdrop that one has to judge the changes that took place after 1956. S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike’s enemies, both within the Sinhala community and the Tamil community, were those from the upper class he came from, the English educated brown sahibs who probably were more British than the British. They were his friends until he decided to espouse the cause of the majority in the country, who did not wish for one set of colonialists to be replaced by another.