Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Friday, 29 January 2021 00:07 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Rupee weakens against key currencies

Rupee weakens against key currencies

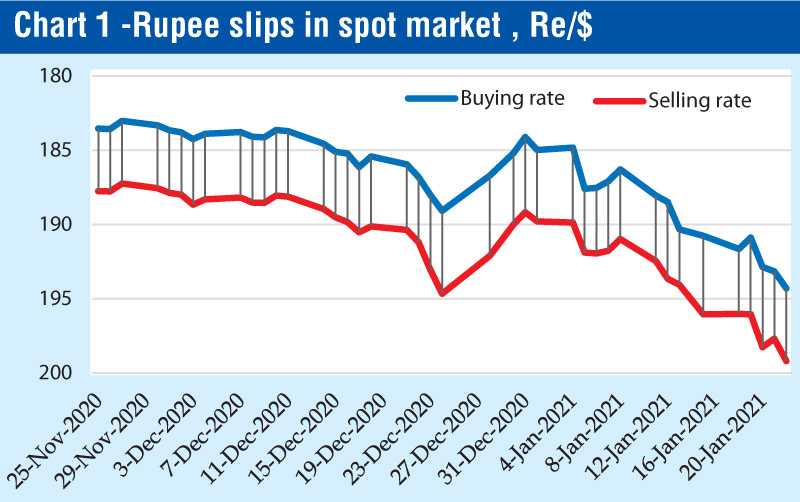

The Sri Lanka Rupee, which has been under severe pressure during the past couple of weeks, slipped to nearly Rs. 200 per US dollar in the spot market last Friday. Banks were selling dollars at Rs. 199.19 (importer’s side) and buying at Rs. 194.31 (exporters’ side). The rupee depreciation has accelerated since early this month (Chart 1).

The rupee depreciated by 7% against the US dollar during the last 12 months. The depreciation was even larger against some other key currencies such as Euro (by 17%), UK Pound (by 13%) and Japanese Yen (by 13%).

The erosion of the rupee is an outcome of several factors. A major reason is the decline in foreign exchange earnings from the export and tourism sectors hit by COVID-19 pandemic. However, the potential import demand pressures that could have emanated from the increased money supply was subdued by the import controls effected last year. Such measures temporarily helped to ease the balance of payments difficulties to a certain extent.

Bond repayments strenuous

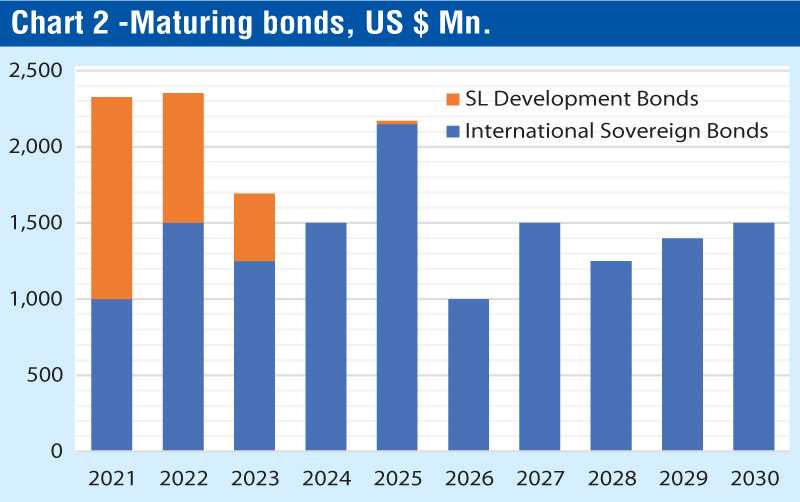

The Government has to settle Sri Lanka Development Bonds amounting to $ 1,325 million by next August. In addition, an International Sovereign Bond of $ 1,000 million will have to be settled in July this year.

The foreign exchange shortage is compounded now by the difficulties faced by the Government in attracting foreign investors to its dollar denominated bonds in recent auctions. This restrains the rolling-over of foreign bonds which are due to mature from this year onwards (Chart 2).

SLDBs becoming less attractive to foreign investors

Reflecting the investor concerns with regard to Sri Lanka’s credit worthiness, the last two auctions of the Sri Lanka Development Bonds (SLDBs) were heavily undersubscribed. In the auction held in November last year for $ 200 million, the Central Bank was able to raise only $ 24.82 million accounting for as much as 67% of undersubscription. The auction held this month which had an offering of $ 200 million raised only $ 43.6 million reflecting undersubscription to the tune

of 78%.

There is a noticeable increase in yields of recent SLDBs, which again is a reflection of the disturbing concerns among foreign investors on the country’s debt servicing capacity. The last auction’s yields ranged between 6.89% for one year and 6.05% for four years.

In comparison, the auction held in January 2020 had lower yield rates ranging between 5.93% for one year and seven months and 5.98 percent for five years. The rise in borrowing costs in such manner too reflects the stringent conditions faced by the country in global capital markets.

Downgrading of credit ratings

The downgrading of Sri Lanka’s sovereign ratings by three leading global rating agencies (Moody’s, Fitch and S&P) five times since April 2020 seems to have adversely affected the country’s access to capital markets.

The rating agencies have expressed concerns with regard to the country’s debt sustainability and deteriorating fiscal situation. They expect that the Government’s liquidity and external risks are likely to intensify in the face of high debt commitments and fiscal deficits that require further external financing. The rating agencies are of the view that the shock occurs at a time when the country’s credit profile is highly vulnerable, given low reserve coverage for heavy debt repayments ahead and weak debt affordability.

Trade deficit is likely to expand

Continuous deficits in the balance of payments necessitate further borrowings from abroad leading to accumulation of external debt.

The trade deficit declined remarkably to $ 5,413 million in the first eleven months of 2020 from $ 7,213 million in the corresponding period of the previous year. This was mainly due to the import controls on non-essential consumer goods and lesser demand for intermediate and investment goods.

Nevertheless, the gravity of the foreign exchange crisis cannot be underestimated, given the fact that the higher GDP growth envisaged by the Government from this year onwards essentially requires larger import volumes of intermediate and investment goods in the coming months.

As regards consumer goods imports, the excessive money supply which is currently growing at 22% a year triggered by increasing bank credit to the Government will certainly have pent-up demand pressures on such imports once the import controls are lifted.

Capital outflows

Exodus of foreign investments from the bond and stock markets makes financing of the balance of payments deficit more difficult.

Despite the stock market boom experienced in recent weeks, there was a net outflow of foreign investments to the tune of $ 209 million up to November 2020.

The bullish stock trading seems to be an outcome of the present low interest rate structure which encourages savers to invest in stocks, physical assets and speculative deals. Evidently, such unusual equity price hikes end up as “stock market bubbles” leaving behind dire financial consequences.

Realisation of larger Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) inflows as anticipated by the Government seems rather difficult in the backdrop of COVID-19 pandemic and global economic downturn.

Foreign reserves hardly sufficient to meet commitments

Official reserve assets amounted to $ 5,665 million at the end of last year whereas the amount of foreign currency required for debt servicing (capital repayments plus interest) within the next 12 months is estimated to be $ 5,797 million. Of this amount, $ 171 million will have to be settled within one month, $ 882 million in one to three months and $ 4,745 million in three to 12 months.

Hence, further foreign borrowing is unavoidable, although the Central Bank contemplates to reduce the foreign debt component of public debt by increased borrowings from the domestic market along the lines of what is called a new economic model.

In this context, printing money to repay debt as prescribed by the proponents of the so-called Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is not a viable option for Sri Lanka, as argued out in my article appeared in Daily FT (http://www.ft.lk/columns/Money-printing-to-repay-Govt-debt-worshipping-MMT-is-likely-to-magnify-economic-instability/4-710612). The simple reason is that the SL rupee is not acceptable in lieu of debt repayments in international capital markets.

Foreign debt accumulation

A country’s external debt usually refers to the foreign debt component of the public debt. But the external debt of the country also includes the foreign debt raised by the private sector as well, since the repayments and interest payments pertaining to such loans have to be met by using the country’s foreign reserves, irrespective of the type of borrower.

Since 2013, commercial banks and blue-chip companies have been allowed to borrow specific amounts of foreign currency from global capital markets. Eventually, the State-owned banks (Bank of Ceylon, NSB, NDB and DFCC) became indirect borrowing sources for the Government.

The outstanding total external debt of the Government, Central Bank, deposit-taking financial institutions and other entities amounted to $ 51.6 billion, which is equivalent to as much as 64 percent of GDP, by the end of the third quarter, 2020. Five years ago, it amounted to $ 43.7 billion, equivalent to 57% of GDP. This reflects the continuous accumulation of foreign debt over the years without showing any signs of debt reduction.

Vicious circle ignored by MMT promoters

As the exchange rate depreciates, the rupee costs of capital repayments and interest payments pertaining to dollar-denominated debt are getting bigger causing a rise in government expenditure, and a consequent expansion of the budget deficit which is likely to reach around 10% of GDP this year.

The Government will have to borrow more and more to finance the increasing budget deficit. Borrowing from foreign sources intensifies external debt burden while borrowing from the domestic banking system, as practiced now, causes high money growth with adverse consequences on inflation and balance of payments.

Thus, budget deficit, government debt, money supply, inflation, exchange rate and balance of payments are caught up very badly in a vicious circle in the case of Sri Lanka. These macroeconomic interactions are totally neglected by MMT promoters who confine their so-called model to a few accounting identities.

IMF assistance inevitable

Given the difficulties in attracting foreign investors to Government’s debt instruments in the face of widening external imbalance, turning to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to obtain balance of payments support seems to be a desirable option, leaving aside extremist dogma. Such support would act as a seal of debt repayment guarantee catalysing private capital flows.

Politically, the IMF-backed programs are resisted by policymakers in many developing countries including Sri Lanka, as they involve structural adjustments with stringent conditionalities which are meant to correct imperfect macroeconomic fundamentals such as budget deficits, exchange rate misalignments and financial sector fragilities. Such policy measures might not be well received in the electorates.

Nevertheless, such domestic housekeeping, which might be bitter at times from the viewpoint of populist politics, is essential not only to achieve economic stability and growth, but also to restore debt sustainability and to build up investor confidence. Approaching the global capital markets without possessing such credibility is going to be very costly and damaging, as already experienced by Sri Lanka.

There is opportunity to seek IMF assistance through its Rapid Financing Instrument (RFI), which is available to all member countries facing balance of payments needs. RFI window provides more flexible support to the needy countries. Access limits under RFI have been temporarily increased since last year to meet large and urgent COVID-19-related financing needs.

(Prof. Sirimevan Colombage is Emeritus Professor in Economics at the Open University of Sri Lanka and former Director of Statistics, Central Bank of Sri Lanka.)