Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Wednesday, 15 July 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

In a short piece titled ‘Modernising Madrasas for New Paideia’ (Colombo Telegraph, 6 February 2019), this author brought home the need for reforms in this historic institution of theological learning in order  to make that learning relevant to modern context, and pointed out the obstruction from orthodoxy to bring any changes to a fossilised curricula and teaching.

to make that learning relevant to modern context, and pointed out the obstruction from orthodoxy to bring any changes to a fossilised curricula and teaching.

Once again, on the eve of a General Election and as part of a wave of anti-Muslim hysteria, populist demagogues in saffron robes are calling the President and his Government to ban the madrasas, Qazi courts and the burqa within one week or, face a renewed campaign to boycott Muslim businesses.

So far, and sensibly, nothing has eventuated. However, this politico-clerical demagogism arises from a Buddhist supremacist fringe that not only wants to downsize the Muslim community in number, but also to destroy its economy and craves to homogenise the cultural landscape of this country – all on the basis of a narrowly conceived sectarian virtuosity and ethno-religious hegemony.

History and development of madrasas

One wonders whether these firebrands have any knowledge about the history and development of madrasas, a unique institution in Islam, whose origins, according to one source, goes back to the days of the Prophet, when the first madrasa was founded on an estate belonged to one of his followers, Zaid bin Akram, near a hill named Safa in Medina.

Over the centuries, as Islam spread to the four corners of the world, the number of madrasas multiplied and quite a few among them became world famous and produced a galaxy of intellectual savants and great scientific minds whose thoughts and writings set the edifice for a rationalist wave of thought, which later led to the European Enlightenment, from which modernity was born. Had the saffron clad ignoramuses studied that part of history, they would be agitating not for the closure but for the recreation of madrasas of such quality and prestige.

Yet, they cannot be blamed for the current disrepute into which madrasa education had fallen. True, madrasas have earned a notoriety in the 21st century and are viewed as centres of religious extremism and violent jihadism, thanks to Ronald Regan’s war against the “evil empire”, and US’s lackey Saudi Arabia that wanted to spread its Wahhabism.

These two, with weapons and training from the first and petro-dollars from the second, entered into and converted many of the then existing Pakistani and Afghan madrasas, but also established hundreds of new ones to produce not learned scholars in Islam, but mujahideen or freedom fighters to drive away the Soviet Communists from Afghanistan, and make US the only remaining super power. Today’s Taliban with whom Trump is trying to negotiate are the product of US-Saudi “eternal friendship”.

Unexpectedly, when the same mujahideen forces, elated by a shared victory against Soviet troops, turned their weapons and training against the original sponsors, the entire institution of madrasa came to be portrayed by US and its allies as manufacturers of terrorism and terrorists. Madrasas suddenly became institutions preaching Holy War, enemies of world peace, hotbeds of Islamic religious extremism and therefore demanded to be shut down.

It is the same sentiment and misconception that is now being articulated in Sri Lanka by maverick Buddhist monks. They are indeed a minority. However and sadly, the Easter Sunday infamy of April 2019, engineered by a lunatic bunch of murderers led by their leader Zahran – a madrasa dropout, and members of his Wahhabi National Tawheed Jamaat, has given these saffron warriors a powerful ammunition to attack not only the madrasas but along with them the entire Muslim community and its other identity markers.

It should be reminded that Zahran was not the product of any madrasa, but a contumacious truant thrown out of a madrasa, who tried to become an autodidact in Islam, went on the wrong way, dragging along with him a group of misguided youngsters some of whom were quite affluent and Western educated, and ended up as a mass murderer.

Madrasa education in Sri Lanka

Madrasa education in Sri Lanka is more than a century old, and, over that period, they have remained as centres of hardened orthodoxy refusing to undertake changes both in techniques of teaching and content of syllabus so that, like in the glorious days of Islamic civilisation, they could produce generations of scholars and critical thinkers, who would be multi-skilled, remain economically independent and knowledgeable enough to respond to a myriad of challenges emanating from a rapidly changing world of science and technology.

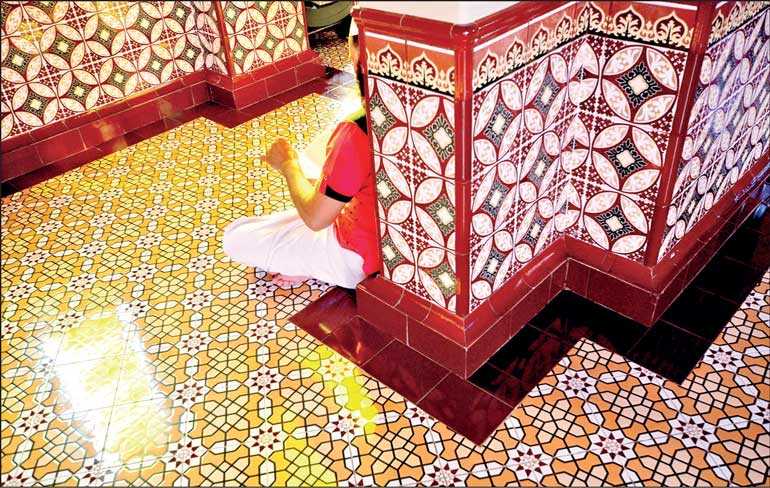

Unfortunately, with impressive buildings and uniformly attired staff and students, madrasas today have become institutions of transmission centres of yesterday’s knowledge and not laboratories of modern research and knowledge creation. With rare exceptions, madrasa products in Sri Lanka are pious agents of orthodoxy rather than creative interlocutors with modernity. They summarise, memorise and regurgitate rather than innovate, interpret and improvise.

Critical thinking is not a discipline taught in any of the madrasas. In short, what they produce are religious functionaries, officiating as imams in the mosques delivering sermons with illogical and non-contextual content, and teachers and trainers of religious rituals. Hardly any of them today are able to have access to the rich and growing source of multilingual output in Islamic history, philosophy and critical ideas that are pouring out from modern research centres. Pathetically, in one of the madrasas that I visited in Si Lanka, its principal did not even allow his students to read newspapers, let alone books outside theological texts of yester decades if not centuries.

This does not mean that madrasas should be banned. Even with the prevailing drawbacks, there is a positive side that justifies their continuous existence. The piety, discipline and morals imparted through madrasa education are a counterweight to a number of social evils that had crept into our schools, colleges and universities of secular education. Moreover, quite a majority of madrasa students like Buddhist kids in pirivenas come from poorer economic background and without the madrasas the chances of these kids becoming misfits in society and falling on the wrong side of the law is quite high.

Reforming madrasa education

Reforming madrasa education should not be a piecemeal affair, but part of a systemic overhaul of Islamic education imparted in elementary maktabs, Muslim schools and even universities. It should be undertaken not by politicians but by Muslim intellectuals and academics who understand the need of the time and the environment in which Muslims live. Once the scheme of reforms is worked out and drafted, it should then be submitted to the government in power through political leaders for approval and implementation. This is the only way to keep at bay the howling voices calling for the closure of this historic institution. In the meantime, an organisation like the ACJU, which is part of the problem, should either cooperate or stand aside.

(The writer is attached to the School of Business & Governance, Murdoch University, Western Australia.)