Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Monday, 19 April 2021 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

If the successive governments of this country provided sufficient technical support and incentives for small and medium scale millers, they would have been a strong force in the market, milling a substantial volume of paddy – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

Introduction

Introduction

The Sri Lankans are blitzed by the statements made by the ministers and officials about controlling of prices of rice, vegetables, and other agricultural produce which are considered as a part of staple diet of the people. It has been observed that there are attempts by the Government to control rice prices recently, which have not realised expected results. There are many more examples that have had the same outcome.

The purpose of this article is to analyse the impact of these initiatives from an economic point of view rather than looking at these efforts to control prices from a political viewpoint. As an approach to this study, the objective of this article is to highlight two myths surrounding agricultural produce marketing which are of great relevance to current issues faced by consumers due to the high prices of agricultural produce.

Myth 1: Removal of middlemen from the marketing channel to reduce prices to the consumer

There is a strong belief that there are far too many middlemen in the marketing channel who tend to increase the end prices to the consumers quoting a very high gap between the farm gate prices and prices to consumers. This may look logical on the surface, however, let us analyse the situation. There is no argument on the functions performed by the middlemen in the marketing channel, functions such as transporting the produce from the farmer to the market, taking the ownership of the product, although for a short period, utilising their finances, break-bulking of the produce, incurring any loses to the product during the transportation is not all but some of them.

The next question that has to be considered is; is it possible remove or do away with these functions? The answer is a firm “no” then there should be someone to perform these functions. As we cannot do away with the functions which are handled by the so-called middlemen if we remove them someone else should do these functions. The next question is who will replace the middlemen and do the above-mentioned activities? The popular options are the government agency to carry out these functions or to create a direct link between the farmer and the seller/buyer.

It is a well-known fact that the Government agencies do not possess sufficient skills in marketing and their bureaucratic approaches never support such activities all over the world, for that matter. The agricultural produce will get perished during the government holidays too! The Government officers do not have the flexibility to handle finances that are required by the free enterprise system. These are just a few reasons to conclude that Government officials are not suitable to handle these marketing activities successfully. Hence, it is obvious considering the difficulties, the Government will face handling the functions of the middlemen, and therefore one cannot consider the Government involvement as an appropriate alternative.

However, about the second option, allowing the farmer or the seller to perform the functions of middlemen would be a futile exercise as both these parties do not have the capacity, finance nor the expertise compared to that of a specialised middleman. If farmers are to perform the middlemen’s functions, they have to sacrifice the time available for farming to do certain activities which are not in their domain or their expert zone. Hence an efficient farmer will become an inefficient middleman. It has also been noted numerous incidents of government agencies failing to handle agricultural produce marketing.

Some of the readers may remember the fate of institutions like, Markfed, Marketing Department which faced a natural death due to incompetence. These simple facts will amply demonstrate that both these options considered above are not practically efficient alternatives to perform the functions which are specific activities of a middleman in the marketing channel. Therefore, it is clear that these are not alternatives to perform the functions of middlemen. Hence, the removal of middlemen is a myth in agricultural produce marketing in Sri Lanka.

Is there a role for the Government in this scenario?

One might think that if the situation is such, the Government has no role to play in reducing exorbitantly high prices of agricultural produce to the end consumers. However, the answer is quite opposite. The Government has a major long-term role to increase the competition among middlemen who perform a vital function in the marketing channel. It is by facilitating the marketing activities of the middlemen by providing infrastructure facilities, can they be offered tax or other financial incentives. Providing them with know-how in reducing wastage of agricultural produce especially post-harvest losses in transportation which is substantially high in Sri Lanka.

There are many other ways to support middlemen in bringing down their operational cost so that competition among them will increase and in turn, the prices they charge will be reduced. This in turn has an impact on the prices of agricultural produce to end-consumer. There are no short-term fixes to solve this problem.

Myth 2: Imposing guaranteed prices by the Government for agricultural produce will help controlling market prices

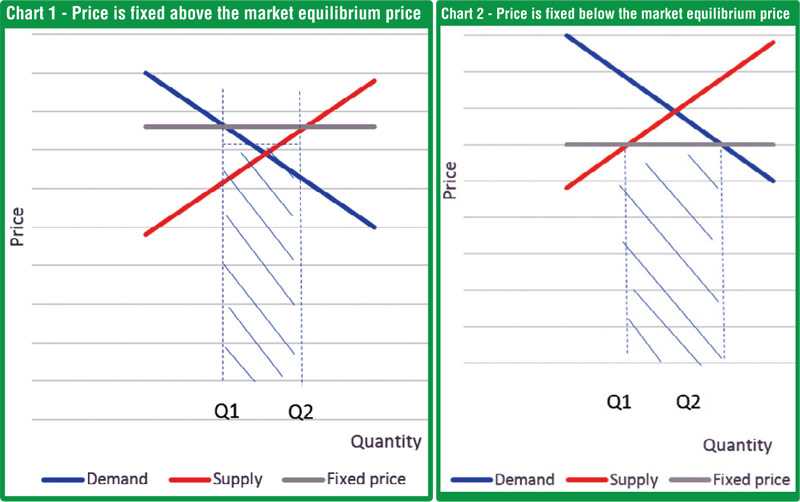

Firstly, we have to accept the fact that Sri Lanka has a free enterprise system (or liberalised open economy) and let us consider what happens when prices are fixed in a free enterprise system. Let me draw your attention to the two following charts to explain the outcome of fixing prices of agricultural produce by the Government.

As shown in Chart 1, the fixed price is higher than the market established price, suppliers tend to supply more to the market for sale (Q2) as they can get a higher price from the Government agency however the market demand is Q1, hence there is an excess supply to the market (Q2-Q1), therefore, the government agency will have to clear/buy this excess quantity. What has generally happened is that once purchases are made, these agricultural products are stored in go downs of the government agencies and perish over time adding an enormous cost to society. We have seen this happening to many food crops such as paddy, turmeric, sesame, etc. Therefore, this option adds more cost and will not deliver the expected results.

As the price is fixed in this case (Chart 2), below the market established price suppliers are not interested in selling to a government agency as the guaranteed price is less than the market equilibrium price. Hence the quantity supplied is Q1. Therefore, imposing a price below the market price is useless and the government will not be able to buy sufficient quantities to influence the prices prevailing in the market. The quantity demanded is Q2. We have seen this happening to many food crops, especially for paddy, recently.

As a result, there could be out of stock (Q2-Q1) situations as this kind of decision will lead to certain suppliers hiding the available stocks. Especially, in a situation that there are only a few large suppliers are controlling the market as small and medium suppliers are defunct. This was very evident in the paddy-rice market where a few large millers are controlling the market. Therefore, in the worst scenario Government may have to import these food commodities which are in short supply to the market though these stocks are available in the country.

Therefore, this option too adds more cost and will not achieve the expected results.

The third option is to fix the guaranteed price at the market price, this option may not be meaningful, as there won’t be an impact on the market price. Further, the Government agency may not be competitive than the private sector in purchasing produce, considering inbuilt Government rules and regulations in buying and selling. The Government officers with their ‘follow the rules approach or maintain status quo’ are no good marketers irrespective of whether they are Sri Lankans or foreigners.

Is there a role for the Government in this scenario?

Is there a role for the Government in this scenario?

Once again, the role of the Government in settling an issue of this nature is not ‘firefighting’ but planning and implementing long-term strategies that are necessary so that these issues do not erupt. In the first place, steps should be taken to avoid the creation of monopolistic or oligopolistic situations.

This can be achieved by developing a large number of small and medium scale supplies of these products, in this case it is rice. If the successive governments of this country provided sufficient technical support and incentives for small and medium scale millers (SME), they would have been a strong force in the market, milling a substantial volume of paddy.

In an issue of this nature the SMEs could pose a strong opposition to these few large millers who now operate without such competition. Having failed to do so, successive governments succumbed to the pressures of large-scale millers and become helpless in reducing the high prices of rice to the consumers and government gazettes have not been effective in controlling such issues.

Concluding remarks

In conclusion, the intention of this write-up is to address the two myths highlighted in this article and analyse them conceptually and drawing the attention of all stakeholders to the ill-effects of believing these myths and taking action accordingly. It is also felt that the necessity of having some expertise in strategic planning as well as marketing approach to this multi-faceted problem which also has a close sentimental link to the farmers of Sri Lanka. But this expertise is clearly lacking with majority of the Government officials.

Further, the policymakers (political and administrative) are appealed to analyse these mythical assumptions before taking appropriate action in resolving the market-related issues. Though, any statistics to quantify the losses are not presented to emphasise the seriousness of these outcomes, it is obvious that society has to pay the cost of implementing decisions based on wrong assumptions. One could also argue that these theoretical concepts will not hold well in practical situations, however, it should be noted that the purpose of the theoretical concepts is to provide a ‘binocular effect’ in analysing and understanding practical issues, which is valid in this discussion too.

(The author has diverse experience in manufacturing, marketing (consumer, industrial, and international), exports, agricultural produce marketing, agrarian research, and in higher education in his 40 years of corporate career. He was a researcher attached to HARTI, Deputy Director of Marketing of the ADA, and the Chairman of SLCARP among many other senior and top management positions held by him in private and public institutions.)