Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Wednesday, 13 November 2019 00:28 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

I have been under pressure from friends and erstwhile colleagues to comment on the election manifestos of the presidential candidates, at least of the three main contenders.

My feeling is that a lot of thought has gone into their preparation and they deserve to be commended for these efforts. They also agree that good intentions expressed by them must be incorporated into plans of action and implemented diligently. Whatever deficiencies and inconsistencies there are in the manifestos will re-emerge at that stage.

When thinking of converting manifestos into national plans, I cannot avoid some nostalgic memories of an encounter with President Premadasa 30 years ago. He had just come into power and had asked two of his confidants in the public service to do a simple job of ‘cut and paste ‘and produce a plan in two days.

Paskaralingam, who had been appointed as the Treasury Secretary and Policy Planning and Implementation Secretary, had suggested that I should be asked as well, as I was the Head of the National Planning Department. However, when Paskaralingam conveyed the message to me, I was shocked. I told him that this is not a job that could be completed in two days, as there was a consultative process involved.

He had conveyed the message to the President. Without getting angry with me, he invited me to Sucharita to talk about it. That was to be my first meeting with him, and I was rather worried and nervous. When I went there, all the security people and aides from the gate onwards knew that I was coming, and I was escorted all the way to his room. Meanwhile, a lot of people, including M. H. Mohamed, were waiting to meet him.

He was seated at a coffee table with a ballpoint pen in his hand and a writing pad in front of him. He told me to sit in front of him and asked me what the problem was with writing the plan; after all, he had told the others that it is a simple ‘cut and paste’ job.

I started explaining the difficulty of completing the task in two days as there was a consultative process involved. I explained to him that the final outcome expected in the manifesto will be, in short, the result of a series of symbiotic relationships involving various inputs and outputs that require resources (capital, labour, technology, etc.) which have competing demands. These have to be assessed, and I need time to consult the specialists in the Ministries of Finance, Agriculture, Industries, etc., which, in fact, was not too difficult since the National Planning Department that I head enjoyed very good working relations with them, but I needed time.

President Premadasa spent more than one hour discussing these issues and agreed that all this could be incorporated into the public investment program which we will continue to produce on a rolling plan basis. To this day, I consider this meeting and discussion with him as one of my greatest achievements in communication. On the other hand, it was a reflection of his patience and capacity to understand and appreciate good advice. When I mentioned what was discussed to my colleagues, they were amazed and started laughing that I had managed to discuss the Leontief input output matrix with the President.

The conditions necessary for successful planning and implementation will become obvious when we consider the imperatives, listed below as “nine C’s” for analytical convenience and memory; such as (1) conceptualisation (2) cohesion (3) consultation (4) coordination (5) collaboration (6) commitment (7) capacity (8) correction, and (9) continuation. A plan must be based on a clear and realistic conceptualisation of the expected outcomes of policies and their implementation. Outcomes must be distinguished from outputs. The government could build thousand houses (outputs) for distribution but they are of little value and could be a waste of resources if they are uninhabitable. Outcomes like outputs must be, as far as possible, quantifiable and have a clearly defined time horizon for achievement. They should, however, not be based on wishful thinking but hard assessment of existing strengths,

opportunities for change, and weaknesses to be overcome, which include external threats

The nine C’s

The conditions necessary for successful planning and implementation will become obvious when we consider the imperatives, listed below as “nine C’s” for analytical convenience and memory; such as (1) conceptualisation (2) cohesion (3) consultation (4) coordination (5) collaboration (6) commitment (7) capacity (8) correction, and (9) continuation.

A plan must be based on a clear and realistic conceptualisation of the expected outcomes of policies and their implementation. Outcomes must be distinguished from outputs. The government could build thousand houses (outputs) for distribution but they are of little value and could be a waste of resources if they are uninhabitable. Outcomes like outputs must be, as far as possible, quantifiable and have a clearly defined time horizon for achievement. They should, however, not be based on wishful thinking but hard assessment of existing strengths, opportunities for change, and weaknesses to be overcome, which include external threats.

The principle of cohesion takes into account the symbiotic linkages that exist among development indicators and forms the basis for stakeholder commitments through a process of consultation, coordination and collaboration.

The way forward

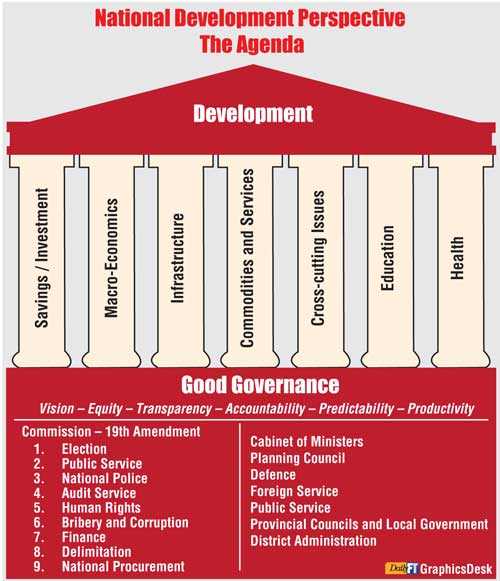

The ‘Greek Temple’ of development shown above is built on the solid foundation of good governance principles. As mentioned earlier, these principles go beyond the oft-repeated good intentions and ethical considerations to performing the functions of technical imperatives. The provisions of the 19th Amendment, as well as the newly enacted Right to Information Act, provide salutary support to the adoption of these principles. Yet, there are serious institutional deficiencies that must be urgently addressed if the country is to be put on a meaningful path of sustainable development.

Cabinet size and structure

The first major constraining factor is the size and composition of the cabinet of Ministers. Sectoral functions have been splintered to accommodate political requirements. A good example of this negative approach, which almost became an international joke, was the political expediency that led to allocating highways and higher education under the purview of one minister.

Cabinet size and structure is very much linked to the role of government and style of governance, particularly the scope of functions to which ministers must confine themselves. They should be concerned with policymaking and implementation and not arrogate to themselves administrative functions, which should be the responsibility of ministry secretaries and their subordinate staff.

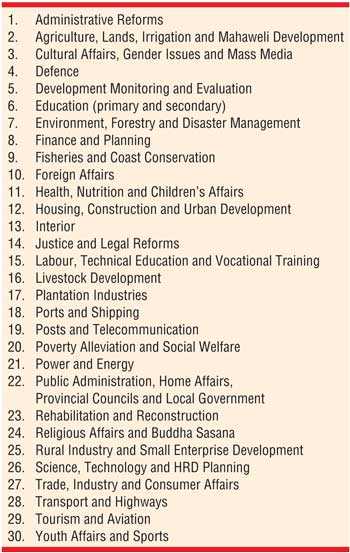

Too large a cabinet certainly adds to costs and also creates confusion. It makes coordination ineffective. Fragmentation and duplication of functions among ministries exacerbate the situation. According to the 19th Amendment to the Constitution the number should not exceed 30 ministers unless it is a national government, which though is not clearly defined.

Ideally, the cabinet structure must follow the principle of intersectoral and intrasectoral coordination. For instance, agriculture (crops), lands and irrigation policies and functions must be coordinated by one minister. The plantation sector can stand on its own, in view of its unique system of management and skills requirement. In most countries, industry and trade are together, in view of their linkages.

Time and space do not permit a detailed discussion of portfolio distribution. The following is suggested as a feasible arrangement, based on the requirements for effective national planning and implementation.

There are two new ministries – the Ministry of Administrative Reforms and the Ministry of Development Monitoring and Evaluation. The need for a separate ministry in charge of administrative reforms will be clear when we discuss the need for a paradigm shift in public administration. An equally important need, which has been almost totally neglected so far, is the establishment of an effective system of project and program monitoring and evaluation. Some attempts made in the past to introduce effective systems failed mainly due to a lack of patronage from the head of government and the cabinet collectively to enforce the necessary discipline and compliance at the implementing agencies which came under different ministers.

Cabinet meetings

Traditionally, cabinet meetings are held every week. The larger the cabinet, the more unwieldy becomes the discussion. The agenda to be effective must confine itself to decisions that have to be made. This means that the ministers must be properly guided with advice through sub-committees. It also means that the ministers who attend these meetings read the memoranda distributed among them. It is a well-known fact that most ministers do not read them, except when they are personally affected.

Cabinet sub-committees

The cabinet, however well-endowed it is with professional capacity, cannot deal with the plethora of issues it is confronted with each week within a short period of (usually) two hours. It needs help through sub-committees that could devote more time, focus and analysis.

Broadly, there must be two types of sub-committees – at least one dealing with issues relating to political relations, both local and foreign, and the others dealing with economic growth and employment, covering mostly macro-economic, sectoral and project concerns.

It is obvious that one cannot put political and development issues into separate water-tight compartments; yet for better focus of attention, the division becomes necessary and feasible. Ad hoc sub-committees, when necessary for greater in-depth analysis and consultation, must not, however, supersede the fixed sub-committees.

National economic advisory council

Even the best of cabinet-sub committees, however, need technical and professional support, with a group of individuals examining each case holistically, deliberating collectively on different aspects of policy and reporting.

This is where a national economic advisory council could be helpful. Its task would be to advise the ministers, inter-alia, how the nine Cs enumerated earlier could be put into practice.

The national economic council should not comprise political cronies but professionals covering various sectors of the economy. Representation of the major chambers of commerce and industry would help achieve the government’s much touted slogan of PPP (public-private partnership).

However, even the best constituted economic advisory council needs technical support. This emphasises the need for a competent technical secretariat. There are two options – either establish a new set up, usually with highly paid professionals, or upgrade an existing organisation, such as the National Planning Department, to perform the defined functions. It is not a secret, however, that the technical capacity and morale of the National Planning Department staff have been seriously eroded due to neglect during the last decade. With appropriate capacity building and motivation, the staff could be quickly upgraded to match international standards of technical competence.

Committee of secretaries

An institution that functioned very effectively as a regular policy coordinating body that helped the National Planning Department as well as the Ministry of Finance and Planning, was the Committee of Development Secretaries in the 1980s and early 1990s, chaired by a Cabinet Secretary and later by highly competent Finance Secretaries. Of course, the current set of ministry secretaries is too large a group (about 47) to form an effective committee for serious discussion. A new manageable group, however, could be formed comprising carefully selected sectoral representatives, with provision for co-opting where necessary.

The old Committee of Development Secretaries met every Tuesday, Wednesday being the cabinet day, establishing a link between a policy advisory and a policymaking body. The National Planning Department which coordinated all sectoral and project related functions at the technical level, streamlined through the Public Investment Program, which was a rolling five-year plan, performed the functions of a secretariat of the Committee of Development Secretaries, preparing the agenda for discussion, writing minutes and follow-up of decisions.

Administrative reforms

It is, however, a time-tested realisation that whatever decisions are taken at the top, they have to be implemented by organisations down the line. This was fully appreciated in 1986, which resulted in the appointment of an Administrative Reforms Committee chaired by an eminent public servant, Shelton Wanasinghe. The establishment of the committee was the result of a struggle by the Minister of Finance, urged by the National Planning Department, to convince President Jayewardene of the crucial need. Normally, administrative reforms would be implemented at the behest of the Ministry in charge of public administration. In this instance, it was the National Planning Department that took the initiative due to a lack of planning and implementation capacity in the periphery, which affected its efforts to achieve effective intersectoral coordination.

The 10-volume report of that committee adorns the libraries of many reputed organisations, both locally and abroad. Its recommendations regarding recruitment, training, performance appraisal and motivation of public servants are still valid. It warned, however, against piecemeal implementation of its recommendations, saying that it will not only be counterproductive but also “dangerous” as it could create new problems. Yet, that is exactly what all governments since then have done, mostly pushed by political considerations.

Sri Lanka, however, cannot go forward without an effective and efficient public service. The private sector may be the ‘engine of growth’, but the ‘engine driver’ is the Government. Administrative reforms, therefore, have become a crucial issue of good governance which needs priority attention. Yet, politicians will only give lip service waxing eloquent about the need and admonishing public servants to be efficient and righteous. The problem is that there are no short-term political gains from comprehensive administrative reforms, while they could be also disruptive of entrenched administrative and political structures and privileges.

The need of the hour, therefore, is a new administrative reforms council, which will be taken seriously by the government.