Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Tuesday, 2 July 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Recent parliament debates concerning defence and security in Sri Lanka were mainly focused on the status of forces agreement (SOFA) between the USA and Sri Lanka. News outlets such as the Maharaja Corporation sensationalised the agreement as a ‘threat to Sri Lanka’s sovereignty’ among various other commentators on the subject. Ambassador Alaina Teplitz had commented the agreement concerning military training and cooperation “is not inimical to the sovereignty of Sri Lanka in any way”. Her Excellency commented the agreement is not yet signed, but under negotiation and will be published once signed. This statement is responsible enough as fears spark of Sri Lanka becoming a US military base. In such a light it is up to Sri Lanka to enter the bargaining table with a strong voice and gain the most out of such an agreement while also evading hegemonic designs and US influence on Sri Lanka’s domestic politics.

Setting the context

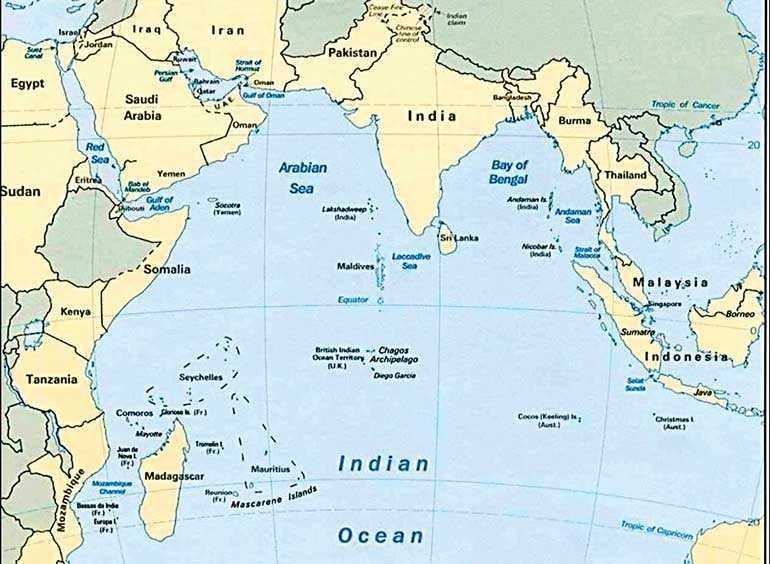

The Indian Ocean Region (IOR) is a highly strategic yet a volatile body of water with heavy international maritime traffic. Often considered the world’s third largest ocean, it carries half of the world’s container cargo. The forces of globalisation has resulted in a surge in shipping trade and competition: more than 80% of word’s seaborne oil trade transits the Indian Ocean. IOR hosts several key developing economies including: China, India, Australia, Singapore, South Africa, and Thailand. A third of the world’s population lives in this region making this area a large market. While acknowledging the strategic significance of the IOR, it is also a highly volatile and a deeply militarised region with a history of strategic rivalries. As world renowned scholars have argued, the centre of gravity of international politics is moving towards the Asia-Pacific of which IOR is at the centre.

In order to prevent militarisation and preserve trade interests’, countries such as Sri Lanka were at the forefront of promoting the IOR as a zone of peace, which has not gained any traction. Today we see a region that struggles to engage in de-militarisation of the oceans while balancing it with concerns of engaging military might to fight ocean crime, contain potential aggressor states, and revisionist powers.

History of militarisation in IOR

Since the age of expedition and discovery, European Powers were traversing the Indian Ocean in search of colonies for conquest. These expeditions subjugated indigenous populations and also made various political, economic, religious and cultural imprints. During the First and Second World War the Indian Ocean was highly militarised. It was in the year 1922 it was decided by USA, Great Britain, Japan, France and Italy to reduce the warships in the region. This was through the signing of the Five-Power Naval Limitation Treaty. The treaty did not however end complete militarisation of the IOR due to the Second World War. Colonies had to enter a compromise that they would fight the coloniser’s war in return for their independence.

The Cold War required the presence of Western Powers in the region to contain Russian influence; a justification for the agreement between USA and Great Britain on British Indian Ocean Territory in 1965. This agreement controversially made provision for military presence in the Chagos Archipelago and Diego Garcia becoming a US military base. While the British removal of naval presence left a vacuum, the United States came to the forefront to fill this void with naval operations conducted through allied forces of both the NATO and EU (European Union Naval Force) for patrolling seas to fight maritime piracy and other ocean crime. The modern facets of ocean militarisation is however, more nuanced and complex in detail.

Prevalence of strategic rivalries

As the centre of gravity in international politics shifted towards the Asia pacific region, the Indian Ocean’s strategic relevance was of concern to both regional and extra-regional powers. Maritime piracy, maritime terrorism, hijacking and armed robbery of ships were considered threats to safety of navigation and transport of cargo. Other ocean crime such as trafficking of drugs, arms, humans and contraband are not direct threats to maritime supply chains but pose human security concerns at regional and state levels. The EUNAFVOR and NATO special anti-piracy operations, joint patrols and sea exercises became quintessential as regional navies and coastguards were not adequate to deal with the threats.

Regional conflicts such as the Persian Gulf War called for American naval presence (7th and 5th fleets) conducting patrols in the Arabian Sea littoral. The revival of US naval presence by amplifying its capabilities through the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue was seen as a response to Chinese influence in the South China Sea, China’s naval modernisation, creation of artificial islands with nuclear reactors etc. In such a light, there are special offshore interests in the Indian Ocean which includes critical islands such as Coco islands, Cocos (Keeling Islands), Sri Lanka and several strategic ports that connects the Malacca straits. For China’s energy dependency, straits of Malacca is critical. Kyaukpyu investment was strategic to reducing this dependency. While the Andaman and Nicobar Islands administered by India gives India a strategic advantage, the Coco islands are vulnerable to Chinese influence. Unsubstantiated reports about the Coco islands being used for Chinese intelligence and naval facilities have formed important security considerations for India.

An analyst from Observer Research Foundation has argued the Chinese influence in Coco Islands near Myanmar provides Beijing with an advantage to monitor the Indian Navy. In a similar manner, Australia’s Cocos (Keeling) islands under a potential US- Australia defence agreement could provide US a similar advantage. These strategic rivalries between China against the bulwark of India, USA, Australia, and Japan working together, creates a highly nuanced militarisation; this is unlike which existed during the colonial or world war era where there was a conventional war to fight which required a militarisation of the Indian Ocean. The modern militarisation of oceans, highly nuclearised dimension, critical energy projects (including the floating Chernobyl of Russia) has created a policy gridlock: one where small littoral states cannot freely choose whether to allow militaristic considerations or not. This is given the backdrop of ocean crime, securing sea lanes, and the need for mutual assistance in humanitarian disasters.

The case of Sri Lanka: contentious defence proposals

Sri Lanka is a goldmine for USA and China among other regional powers due to its highly strategic location. Sri Lankan ports had witnessed a history of militarisation which includes: the natural port of Trincomalee used as a dual purpose port by British Royal Navy during the Second World War. The modern fear is militarisation of the Magampura Mahinda Rajapaksa port by the Chinese which was dispelled by Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe who remarked: “Many people consider that the Hambantota port is a Chinese military base. I accept that there will be an army camp. But it is a Sri Lanka Navy camp. Once installed, a Sri Lankan Rear Admiral will be in control. Any ship from any country can come there. But we control the operations.” Irrespective of the Sri Lankan premier being domestically unpopular, he is internationally very well received and is considered a competent man even in matters of defence. The Easter Sunday Attacks of Sri Lanka was a good example of President Sirisena’s [commander in chief of the armed forces] failure to act timely despite warnings from Sri Lanka’s chief of National Intelligence. The US defence proposals therefore come in a timely yet an odd manner: these include mechanisms to set up exchange of Terrorist Screening Information, operation of US telecommunication and radio spectrum, Acquisition and Cross services Agreement (ACSA) and Status of Forces Agreements (SOFA).

The first Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) was signed in 1995 by President Kumaratunga’s government. It is the most recent SOFA under negotiation which created controversy by both parliamentarians and other spectators calling for more transparency; this includes veteran journalist Lasanda Kurukulasooriya. The SOFA agreement is what essentially prevents the prosecution of US defence personnel from being prosecuted in a foreign jurisdiction where they are being hosted by party to the agreement. The SOFA is dangerous in the sense it provides a wide range of immunities and exemptions to US personnel. These include: ability to by-pass all local licensing authorities which is covered under their definition of “all professional licenses”, exemption from local custom inspections of department equipment, free movement of department personnel throughout Sri Lanka without the payment of overland transit tolls and payment of other tolls collected for public revenue. Although some of these may not be sovereignty-specific issues, it emanates a very strong sense of American Exceptionalism when the US department personnel are above the established rules, and regulatory mechanisms of the host state.

Irrespective of the above concerns, Sri Lanka also has quite a lot to gain if Sri Lanka had strong negotiators backed by the country’s premier and military intelligentsia, as opposed to charlatans that posit themselves as “national security advisors”. The former Defense Secretary Gotabaya Rajapaksa, although considered a dangerous man, was one such strong negotiator who bargained and signed the Acquisition and Cross Services Agreement in 2007. This agreement on reciprocal defence services concerning logistical support, supplies and services were signed at a time when the LTTE was at its strongest. The most recent ACSA agreement did not come in under any extraordinary circumstance unless we were to interpret the Easter Sunday Attacks as being a trigger event for US-Sri Lanka enhanced defence co-operation.

Nevertheless, one should not blatantly attack the US for encroaching on Sri Lankan sovereignty at a time when multilateral defence assistance is needed to combat various vices, including transnational organised crime in both land and maritime domains.

Therefore, Sri Lanka as a small state should consider defence co-operation, albeit carefully studying and knowing when to draw the line.

Points of negotiation for more clarity and reduce the asymmetry in the benefits

Terms relating to Equal Value Exchange:

Natasha Fernando is a blogger and occasional columnist on matters pertaining defence and security. She is based in Colombo, Sri Lanka.

She was a former researcher at the Institute of National Security Studies Sri Lanka. Her views are

independent.