Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Tuesday, 2 March 2021 01:40 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The Government has been increasingly depending on borrowings from the Central Bank (CBSL) and commercial banks to finance its growing fiscal deficit in recent months. This has resulted in a rapid increase in the country’s money supply.

The Government has been increasingly depending on borrowings from the Central Bank (CBSL) and commercial banks to finance its growing fiscal deficit in recent months. This has resulted in a rapid increase in the country’s money supply.

The excessive accommodation of fiscal requirements has weakened CBSL’s monetary management to a large extent. Hence, fiscal discipline, coupled with central bank independence, is essential to put monetary management on the right track.

Fiscal dominance

The budget imbalance has led to a situation of “fiscal dominance” in which CBSL tolerates expansionary fiscal policy by accommodative monetary policy. In contrast, “monetary dominance” prevails when monetary authorities focus entirely on controlling inflation, irrespective of budgetary requirements.

The CBSL has directly accommodated the budgetary requirements by purchasing Treasury Bills in recent primary auctions. In return, CBSL usually issues an equivalent amount of new currency (notes and coins).

However, the decline in CBSL’s foreign reserves and other domestic assets largely offset the impact of government borrowings on currency issues, and therefore, the actual amount of money printed was much less than the exaggerated figures quoted by some critics.

Strangely, CBSL has not rectified such widely-circulated misleading information. Overall, the decline in foreign reserves and slow private sector credit growth have provided leeway to the Government to borrow excessively from the banking sector which is likely to disappear in case of a reversal of those two factors.

Budget pressures across the world

In the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, budgetary difficulties of governments across the world have prompted central banks to suppress monetary dominance. The government debt in advanced economies is projected to increase rapidly during this year, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The projected scenarios for developing countries are even worse.

As in the case of Sri Lanka, many emerging economies have been facing a new wave of sovereign debt rating downgrades in the backdrop of the pandemic. Central bank accommodation of governments’ credit needs in several countries has further worsened the credit ratings.

Remittances from citizens of developing countries working abroad are expected to drop by more than 20% this year, according to IMF reports. Simultaneously, borrowing needs have gone up in developing countries, as they struggle with severe budgetary stresses and balance of payments difficulties.

Composition of money supply

A country’s total stock of money in circulation among the public at a particular point of time is called money supply. It can be categorised as (a) narrow money [M1] consisting of currency and demand deposits with commercial banks, and (b) broad money [M2] consisting of M1 plus time and savings deposits with commercial banks.

Credit creation

Credit creation

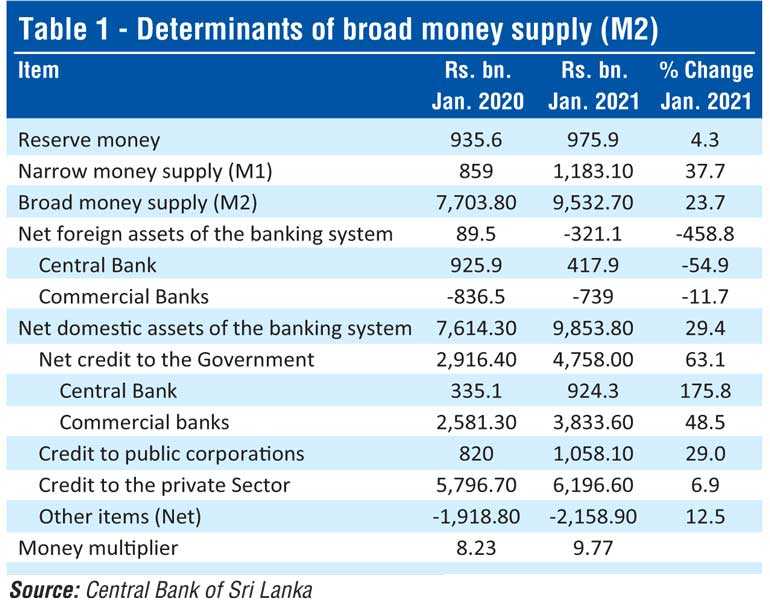

In Sri Lanka, the broad money supply (M2) rose by 23.7% on Y-o-Y basis during the last 12 months (Table 1).

This monetary expansion was largely due to a substantial increase in bank credit to the public sector. The outstanding amount of net credit to the Government rose by 63.1% to Rs. 4.8 trillion in January 2021 from Rs. 2.9 trillion a year ago. Of this amount, net credit provided by CBSL increased almost three-fold to reach nearly Rs. 1 trillion by last month.

Net bank credit to public corporations rose by 29%, and stood at Rs. 1.1 trillion in January.

This is in contrast to the slower pick up of private sector credit only by 6.9% during the last 12 months, as I explained in a previous Daily FT column (http://www.ft.lk/columns/Bank-credit-to-private-sector-picking-up-at-slow-pace-in-response-to-monetary-easing/4-712502).

The monetary expansion was due to credit creation by commercial banks by multiple times of the reserve money. The money multiplier, which measures the link between the money supply and reserve money, is around 10 now. This means that commercial banks have created money in the form of bank deposits as much as 10 times of reserve money.

Money printing exaggerated in media reports

In recent media reports, it is alleged that CBSL prints truckloads of money week after week to meet the budgetary needs.

Top CBSL officials themselves have fuelled the sensations by bringing the phenomenon of ‘money printing’ into the limelight by way of making some irrelevant references to the nonsensical Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), which asserts that public debt commitments can be easily met by printing money instead of mobilising tax revenue. The very same concept of money printing, which is not a legitimate term used in monetary policy or monetary economics, has boomeranged the CBSL with a barrage of criticism, which seem to be unfair to a large extent.

Critics’ figures of money printing too high

According to some critics, the amount of new money printed by CBSL in 2020 was around Rs. 650 billion and yet another Rs. 50 billion was printed in the first two weeks of this month.

The above figure of Rs. 650 billion seems to have been derived by computing the difference between the CBSL’s Treasury bill holdings which rose from Rs. 75 billion at the end of 2019 to Rs. 725 billion at the end of 2020. Similar exercise must have been done to derive the figure of Rs. 50 billion for this month as well.

Methodically, these computations are wrong, as Treasury bill holdings are only one component of the money supply process, as explained below.

Actual amount of currency printed is much less

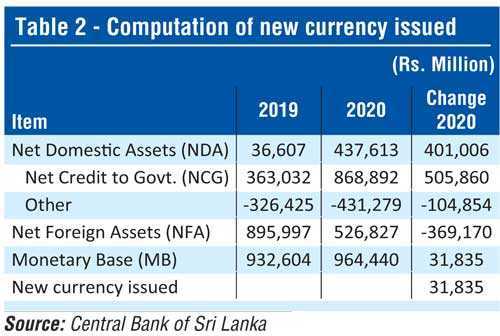

In terms of the Monetary Law Act No. 58 of 1949, CBSL has been empowered as the sole authority to print money or what is called currency (notes and coins) on behalf of the Government. This component of money supply is the one that has been subject to much controversy these days. In contrast to arbitrary increases in the printed money stock as alleged by several critics, CBSL uses changes in the monetary base or reserve money as the basis for new currency issues (Table 2).

The monetary base consists Net Domestic Assets (NDA) plus Net Foreign Assets (NFA). NDA includes Net Credit to the Government (NCG) and other domestic assets/liabilities.

NCG rose by Rs. 506 billion in 2020. This means that CBSL bought that amount of Treasury Bills and Bonds during the year. Theoretically, CBSL should have issued an equivalent amount of new currency. But such impact of NCG was largely offset by a decline in NFA by Rs. 369 billion and other domestic assets by Rs. 104 billion in 2020.

Hence, the actual amount of currency issued by CBSL or newly printed money was only Rs. 31.8 billion in 2020 reflecting only 3.4% increase over 2019. This is much lower than the exorbitant numbers quoted by some critics.

Monetary policy space restricted

Following its monetary policy framework, the CBSL adjusts NCG from time to time by using Open Market Operations (OMO) so as to achieve its monetary policy targets. For instance, when there is a substantial increase in NFA, the CBSL can sterilise the resulting excess liquidity to avoid inflation by selling a part of Government securities in its hand through OMO, and vice-versa.

However, CBSL would not be in a position to mop up excess liquidity in such manner, when it is compelled to hold excessive Government securities, as experienced at present.

In addition, excessive Government borrowings prompts CBSL to maintain low interest rates to avoid aggravation of debt commitments. The CBSL continues to keep its policy interest rates down in recent months, on the grounds of low inflation figures drawn from the Colombo Consumer Price Index (CCPI). However, the Producer Price Index (PPI) reflects inflationary pressures, as explained in my earlier Daily FT column (http://www.ft.lk/columns/Inflationary-pressures-on-the-horizon/4-712891).

Hence, in time to come it might be necessary mop up excess liquidity by selling CBSL’s holdings of Government securities and raising policy interest rates. This would not be feasible, if the Government continues to depend on bank borrowings.

If CBSL’s NFA goes up in the near future by any chance, as predicted by the authorities, it would be essential to reduce NDA through open market operations so as to sterilise excess liquidity to avoid inflation. This again will be unviable due to CBSL’s current accommodative monetary policy.

Fiscal-monetary policy mix

It is widely recognised that freeing central banks from political interference is essential to conduct monetary policy to achieve price stability.

However, worldwide empirical evidence suggests that central bank independence is only a necessary condition, but it is not a sufficient condition to attain price stability. The reason is that the Government’s budgetary constraints might bind the monetary authority to exercise accommodative monetary policy, and thereby limiting its ability to control inflation.

Hence, it matters how fiscal and monetary policies are coordinated compromising the monetary dominance vis-à-vis fiscal dominance.

Fiscal responsibility imperative

In an effort to arrest fiscal dominance in Sri Lanka, the Fiscal Management and Responsibility (FMRA) Act was enacted in 2002 with a view to introduce strict fiscal rules. The two prominent objectives stipulated in the Act were (a) to reduce the government debt to prudent levels by ensuring the budget deficit does not exceed 5% of GDP from the year 2006 onwards, and (b) that total government liabilities (including external debt) do not exceed 60% of GDP commencing 2013.

Since then, however, the fiscal authorities have failed to comply with the rules pertaining to the budget deficit and debt as stipulated in the FRMA. This was due to the rise in expenditure for infrastructure development, social welfare, salaries, debt repayments, interest payments and transfers to loss-making state enterprises. The revenue shortfalls that arose from the arbitrary tax cuts in recent times have aggravated the budget deficit.

Thus, legal (de jure) fiscal targets enforced by the Act have little meaning in actual practice (de facto).

In view of the above analysis, it would be prudent to reactivate the FRMA to enhance fiscal discipline so as to insulate the CBSL from political pressures.

(Prof. Sirimevan Colombage is Emeritus Professor in Economics at the Open University of Sri Lanka and Senior Visiting Fellow of the Advocata Institute. He is a former Director of Statistics of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, and reachable through [email protected])