Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Wednesday, 17 June 2020 00:15 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

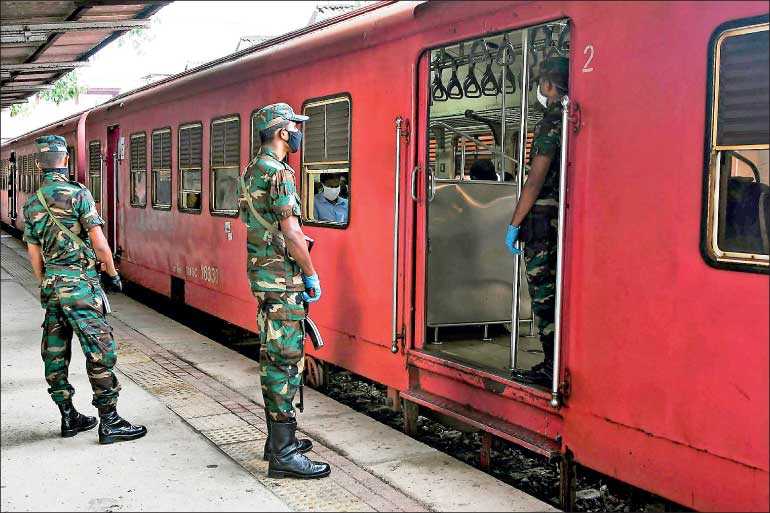

A politicised military serves only the interests of a single political party. In doing so this undermines public confidence in representative democracy and the preservation of national security as a national goal. The politicisation of the military appears to be rooted in myths that have shaped a dominant narrative on military rule – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

By Harindrini Corea

The armed forces or the military primarily defend a nation from enemies within and without. Military strength goes beyond warfare, and includes functions within a nation, including responses to internal security threats and involvement in emergency services and reconstruction.

The military is traditionally an apolitical and nonpartisan institution that acts professionally in serving the interests of the nation whilst being subject to civilian political leadership and political institutions. However, politicisation of the military distorts the true purpose and function of its existence.

A politicised military serves only the interests of a single political party. In doing so this undermines public confidence in representative democracy and the preservation of national security as a national goal. The politicisation of the military appears to be rooted in myths that have shaped a dominant narrative on military rule.

This article explores these enduring myths of military rule by exploring these beliefs in more detail and looking at the countries in which military governments have been formed.

What is military rule?

Military rule, as opposed to civilian rule, is where political power resides with the armed forces. A military dictatorship or military junta is an authoritarian state which is run by the military. It is either led by a dictator with absolute power who is often a high ranked military officer and/or a government led committee of military leaders. Thus the political structure of a military state places high-level military officers in a position to influence policy and political appointments.

Military regimes are rarely purely military in composition as there is always a partnership between politicians, civil bureaucrats, elites and the military. However, the military has the final and overall decision making power. A military dictatorship is usually formed after the previous civilian government has been overthrown though military action.

|

|

On the other hand, military juntas are also formed where civilian government is formally maintained whilst the military exercises de facto control over political power and certain areas of policy. Military rule is also characterised by the lack of political opposition and the political patronage towards loyal supporters of the military regime at the expense of the general population.

There are several myths that surround and perpetuate the justifications for military rule. These beliefs include that military rule is not as corrupt as civilian rule, that a benevolent dictator can create a non-corrupt society, that there is a higher standard of discipline within military regimes and that a military regime is a better alternative to a failed democracy.

Myth of military rule as ‘non-corrupt’

Perception of the military

There is widespread belief of the armed forces as an institution of integrity and trustworthiness that serves its nation. The Global Corruption Barometer (2006) survey which assesses the perceptions of the public in countries around the world on whether the military is perceived to be corrupt, revealed that the military is generally regarded as clean, rather than corrupt.

In Germany and France there is a strong perception of the integrity of the military. In Israel, the role of the military in warfare, has largely contributed to the perception of the military as dedicated and clean handed. In Czech, the positive perception of the military was in contrast to the perception of the Ministry of Defence, particularly with regard to defence procurement, which was subject to several corruption scandals. In Russia, the negative perception of the military was explained by a several factors including a series of corruption scandals in the military and widespread information about the practice of brutal behaviour of the officials and senior soldiers in the military. In Ukraine, the secrecy of the military, meant that there was less public awareness on the existence of corruption within the military.

Non-corrupt benevolent dictatorships

Singapore is usually held up as the poster child for a non-corrupt dictatorship. Whilst the Singaporean dictatorship is not a military regime, it is looked at in brief in this article, to investigate the belief that a government led by a benevolent dictator can be cleaner than a civilian government.

Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, the ‘Father of Independent Singapore’, is usually viewed as an incorruptible and well-meaning leader, with absolute control and no restrictions on power, who developed and transformed his nation. There are several key factors that seem to be important in the development of Singapore sans corruption.

The first is that, whilst there was elimination of political opponents and consolidation of a one party state, ruling officials and policy makers at the inception of the one party state in 1959 were all those with high levels of personal integrity and formal education, particularly extensive training in economics. High public sector salaries were introduced and maintained in order to attract and include experts and the computation of salaries of ministers, judges and senior civil servants was changed to be automatically tied to the amount of income taxes paid by the private sector.

The second, is that the requirement for a non-corrupt and clean government was prioritised from the top down. Lee Kuan Yew himself and other high ranking officials have been investigated for impropriety and all officials are held accountable under the law with no immunity or exceptions.

An interesting statement was made by Lee Kuan Yew, upon being investigated, where he said the following: “I take pride and satisfaction that the question of my two purchases and those of the Deputy Prime Minister, my son, has been subjected to, and not exempted from, scrutiny... It is most important that Singapore remains a place where no one is above scrutiny, that any question of integrity of a minister, however senior, that he has gained benefits either through influence or corrupt practices, be investigated.”

Accordingly, the third, is the combination of stringent laws against corruption, enforcement of such laws and a society that demands a clean government. The Prevention of Corruption Act (PCA), placed the burden of proof on the accused to show that he acquired his wealth legally. The Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau (CPIB) is an independent body, empowered to investigate into corruption, and has focused on bribe-takers in higher levels of government as well as all officials and their families.

The CPIB has the power to investigate bank accounts, property and assets of officials and determine if such individuals are living within their means. Where an official was determined to be living beyond their means or had property that could not have been acquired on their income it was presumed that this was as a result of bribes or corrupt activity. Therefore, the government official under investigation would then have to prove that they have not received such income or property as a result of corruption. Where the official was proven to be guilty, his property was subject to forfeiture and sanctions included fines and imprisonment. The CPIB also contribute to the shaping of a society that expects a clean system, does not condone giving or accepting bribes to get things done and reports corruption.

It can be argued that these factors dismantle the myth of the benevolent dictator being able to establish a clean government. The determination to hold all officials accountable, even those at the highest levels of government, and the creation of a clean society in itself, seem imperative in contributing to a clean government. It is apparent that strong institutions play an important role in ensuring that even a strong leader himself is held accountable under the law.

Non-corrupt military rule

The histories of several countries ranging from Latin American countries to African countries reveals that whilst the goal of military rule may be to establish a non-corrupt military regime this remains as a goal and is not practically implemented.

Busting the myth of non-corrupt military rule

The reality of military rule, subject to limited exceptions, is that it facilitates corruption. The politicisation of the military, the involvement of the military in policy making and decision making and the lack of scrutiny over military actions exacerbates the abuse of power for private gain. An increase in military spending where military commanders hold positions in part of the government machinery, or where democratic governments are replaced by a military regime, leads to a reduction in spending on education, health and welfare.

Military commanders, in strengthening their political power, will hold high level bureaucratic and administrative posts and exploit such posts for private gain. This necessarily also involves the collusion of military elites with political, administrative and bureaucratic elites in society and the exclusion of the general population from the economic and political decision making processes. This may be seen in the awarding of government contracts to specific private companies and the manipulation of tenders for monetary gain.

In the case of military procurement, a lack of competition and accountability, leave space for kickbacks and other financial rewards. The collusion of the military elites and political, administrative and bureaucratic elites is consolidated and strengthened by the kickbacks and payoffs that maintain such mutually beneficial arrangements. The weakening or nonexistence of democratic institutions, such as the legislature and the judiciary, and the exclusion of the general population from military governance, consolidate the abuse of power and corruption.

Transparency International Nigeria: “Thus the military which entered into Nigeria's politics as physicians for corruption ended up as patients in coma of the ailment of corruption.”

The first military coup in Nigeria on 15 January 1966 was based on the desire to cleanse the nation of corruption. However, the military regime of General Yakubu Gowon, was overthrown in a coup led by General Murtala Mohammed, in an attempt to respond to the overwhelming corruption that had become the norm. The second republic led by Alhaji Shehu Shagari was also overthrown because of corruption. General Mohammed Buhari’s regime was overthrown by General Ibrahim Babangida under whose regime corruption became institutionalised in Nigeria.

The Nigerian military in viewing itself as the saviour of Nigeria, saw decisive leadership as the solution for all problems in Nigeria. However, the issues that motivated military intervention were the symptoms rather than the substance of the crisis of underdevelopment in Nigeria. Military involvement in decision making and the ‘settlement syndrome’ whereby perceived opponents had to be ‘settled’ with bribes using state resources did not resolve but rather intensified economic crisis in Nigeria.

The myth of discipline within military regimes

Discipline within the military is a form of behaviour that is designed to ensure compliance to orders within a command hierarchy and is the result of indoctrination and training. Military discipline is operated with a carrot and stick approach where conformity leads to benefits and rebellion incurs punishments. It is widely believed that the military ethos of discipline and service can be followed by a military government and be applied to citizens in the country as well. However, it can be argued that it is indiscipline, rather than discipline, that characterises military governments.

On the one hand, the scrutiny and supervision of citizens carried out by military governments ensures total obedience of subjects to the regime and suppression or elimination of any opposition or dissent. This creates the desired discipline or order within society. On the other hand, where military leaders, or civilian leaders in collusion with the military and elites, abuse their power for financial gain, there is a lack of discipline or order, within the military government. The impunity of dictators or military rulers in economic corruption illustrates this lack of discipline.

Mugabe’s military regime in Zimbabwe provides insights into the symbiotic relationship between the executive and military and patronage politics. Whilst Mugabe remains firmly in charge of the country both retired and serving military officers are deployed in institutions such as the bureaucracy. The military suppress opposition and civil society threats and in return demand political influence and material rewards. The redistributive nationalist rhetoric adopted by the military regime shields the true purpose of the military in serving the interests of Mugabe and his ruling party.

The myth of failed democracy

A popular belief is that where there is a failure of democracy there is a necessity for a dictatorship or military rule. It is primarily corrupt and inefficient civilian politicians that triggers the desire for transition from civilian to military rule. However, it is a misconception that military rule is far more beneficial than civilian rule. This is because the essence of the military; its discipline and non-corrupt nature, cannot be put into practice by a military regime. The military leaders of military regimes do not have the mandate of the people to represent them and cannot be held accountable for their actions. Furthermore, the monopoly of power leads to abuse of power, corruption and indiscipline. Moreover, whilst citizens may find it easy to demand for or support a military regime, there is no choice in whether there should be an end to a military regime.

The process of democracy, however flawed, is a lively process, in which citizens can play an active role in determining who represents them and how diverse interests are represented. In this instance it is the citizen that choses to ensure that corrupt and inefficient politicians are not re-elected and that sitting officials are held accountable for their actions.

It is the citizen who is disciplined to live within their means and not take a bribe or give a bribe. Therefore, where there is 'failed democracy' this is due to the failure of the citizen rather than the ruler; for the citizen has forgotten that it his/her mandate and power that is to be exercised by the ruler. It is the citizen who needs to demand that the power of the ruler is kept in check by a bold opposition in Parliament, a strong judiciary, independent institutions and free media.

Conclusion

The truth behind the myths of military rule is exposed by the realities of countries which have experienced military rule. The enduring myths of military rule persist in countries that desire such rule and are replaced with the truth in countries that have been governed by military rule. The myths and the truth behind the myths leave us with the question of whether we, as citizens, make the choice to relinquish our power or ensure that it is exercised in our best interest.

[The writer is an Attorney-at-Law, LLB (Hons), DipFMS.]

References