Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Tuesday, 1 December 2020 00:33 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

COVID-19 the game changer

COVID-19 the game changer

COVID-19 the global pandemic has impacted many countries in the world and there have been unprecedented adverse business and economic impacts to nations. However the pandemic has unveiled importance of adopting technology and network of Information systems which connected people for maintaining and continuing regular business tasks and customer services, while public sector learned the lack of technology adaptation crating struggles and delays in providing necessary services to general public.

In the Sri Lankan context the flexibility and adoptability to a pandemic of this magnitude was challenging for the majority of businesses while some businesses who had already adopted technology driven transformation and digitalisation were able to respond well to the crisis.

The public service sector mostly driven by Government was greatly impacted by the pandemic and long lock-down times and health and safety regulations have impacted the efficiency of providing public services. Further the low adoption level of technology was noted across all public services and the need for technology driven transformation is important in the current context than ever before.

COVID-19 impact on court proceedings

It was identified that due to COVID-19 court hearings and justice system have faced greater delays and many challenges. The court hearings are open for public unless otherwise restricted by the judge before COVID-19 struck the island.

Due to COVID-19 courts were closed for months, which resulted further delaying the hearing process and justice and once they were opened only a restricted number of people were allowed to the court premises for hearing. People have missed certain appeal deadlines due to difficulties of meeting lawyers and not having timely legal advice.

Further the prisons were overcrowded and it has a direct effect from delays in the trials and judgements. News reported that President Gotabaya Rajapaksa has pardoned over 400 prisoners held for minor offences to minimise congestion in local jails. Officials stated that currently there are over 33,000 prisoners in the country's jails, which have the capacity for 11,700 inmates only. We have encountered near misses in spread of COVID-19 virus among prisoners during the recent months. Therefore it is important understand how these issues in the legal system were addressed by other countries.

An overview of Sri Lanka’s legal system

Sri Lanka is a unique country where a mixed legal system is adopted and it includes Roman-Dutch law, Kandyan law, English law, Thesavalamai and Muslim law. The arrival of the Portuguese fleet of ships in the port of which is now called Colombo in 1505 was the beginning of the colonial era of Ceylon.

The Portuguese fleet commanded by Lourenco de Almeida went on to gain control of the coastal areas of the island and the Roman-Dutch law became the general and common law in the island. Later in 1815 when the Kandyan Kingdom fell to the British, for the first time in history the entire island was under the control of British administration.

The British initially continued to apply the existing common laws of Roman-Dutch law and extended the applicability to the entire country. Further in 1829 the British Colebrooke-Cameron Commission, in 1927 the Donoughmore Commission and in 1944 the Soulbury Commissions have redefined the administration system and body of English law was introduced together with the existing Roman-Dutch law.

Since the independence from British rule in 1948 the structure of the legal system continued up until 22 May 1972 with the new constitution after becoming a republic being adopted and the court structure was defined and Supreme Court became the highest and final court of record and in 1978 the new Constitution which is currently adopted was introduced.

However until 1998 Sri Lankan court procedures are fully dependent on three types of evidences were Oral evidences of eye witnesses, manual paper-based documentary evidence and identification of Martials other than documents (hard evidence). In the famous case Benwell v Republic of Sri Lanka where acts of financial malpractices that were done through Australian property mortgages and evidence were presented as information gathered from computer systems in Australia and at this juncture it was unveiled that soft evidence was not recognised by our legal system as valid evidence. The traditional term ‘document’ also did not interpret the information in a computer system or on a screen.

This gap was addressed only in 1998 by the Act No. 14 which recognised two types of evidence: Computer evidence and audio and video evidence. Since 1998 modern technological evidence is adopted by the court system in Sri Lanka. To address several legal deficiencies in terms of policy and changes in macro environment Sri Lanka has introduced Intellectual Property Act No. 36 of 2003 which provides protection for computer software and other intellectual outputs in the ICT sector and further strengthening of Monetary Law Act as amended by the Act No. 32 of 2002 paved the way for introducing Scripless Securities Trading in the Public Debt Settlement System. It created a central depository and a settlement system for transactions on an electronic basis.

The Payment and Settlement Systems Act No. 28 of 2005 laid down the procedure for the payment of cheques electronically presented. It set up an image-based cheque clearing system, which replaced the physical cheque with electronic information flowing throughout the clearing cycle. This process eliminated the actual cheque movement in cheque clearing and reduced the delays associated with clearing (N. Gunawardena, 2017. ‘Digital Transformation in Sri Lanka: Opportunities and Challenges in Pursuit of Liberal Policies’).

The Computer Act of 2007 was introduced to deal with social media and computer crimes. However Sri Lanka yet to introduce a Data protection act were in some of the recent cases it was evident that some of the Telecommunication data were not provided for courts on the basis they are lost and deleted. There is no law which obligates such institutions accountable in this context (K. Indratissa. 20 September 2020, ‘The Importance of Digitalising Court Procedure,’ Sunday Observer).

Digital transformation potential in Sri Lanka

At the outset Sri Lanka is well positioned for a digital transformation of the legal justice system where during the World Economic Forum’s Networked Readiness Index ranked Sri Lanka at No. 63 out of 139 countries assessed in 2016. Sri Lanka scored relatively high in terms of ICT skills, affordability, governmental ICT usage, and social impacts.

At policy level, the Government has identified telecommunication and digital infrastructure as digital transformation in Sri Lanka. The legal framework for a digital economy has improved significantly, but institutional arrangements are still lagging behind.

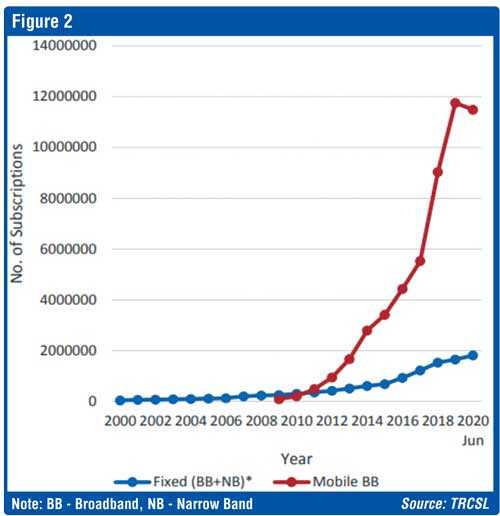

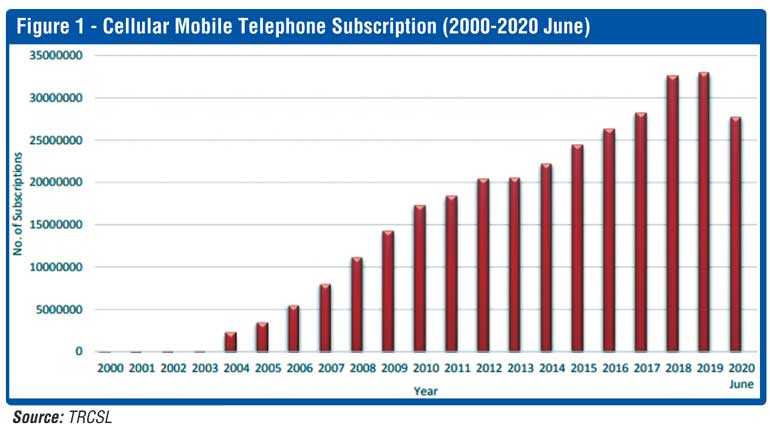

For example, e-commerce faces significant operational obstacles due to regulatory issues (N. Gunawardena, 2017). Furthermore Figure: 1 indicates the drastic increase in cellular mobile subscriptions over the last decade and currently about 31.8 million subscribers (149% of population) exists in the island. Statistics of internet usage has reached nearly 12 million by June 2020 (more than 50% of population) (Figure: 2). This indicates that vast majority of Sri Lankans are using mobile technology, applications and internet which is seen distributed all over the island according to latest statistics of TRCSL.

Further statistics have indicated 74% of the population has an account with a bank and internet-based payment systems are fast growing amid COVID-19 and many private sector companies have introduced online payment gateways. Although some of the elderly and people who live in rural areas may have to be supported by the respective lawyers and or a system created by Police Department, it is evident that the digital transformation could be penetrated into the mass population in Sri Lanka.

International context of digital transformation of court procedures

In the international context, Abu Dhabi Global Market Courts was identified as the world’s first digital court room which was opened in May 2016. Where they operates in English language and follow UK Common law with a Memorandum of understanding with the UAE Ministry of Justice and with Australian, Singapore, Hong Kong and Commercial Court of London.

This has enabled prosecutors, defendants, witnesses’ lawyers and judges to participate from anywhere in the world through the digital court room via advance video technology. This has saved time and improved the efficiency of the judicial proceedings drastically in Abu Dhabi. This has introduced a digital court file, electronic filling capability for documents, electronic hearing and trials, electronic case management, electronic evidence bundling, simple online registration and fully digitised court room.

In UK Online Dispute Resolution for Low Value Civil Claims was proposed in 2015 by Prof Richard Susskind and the following year, Lord Justice Briggs, in his Final Report on the Civil Courts Structure Review in July 2016 proposed the introduction of a new Online Court. In September 2016, in a joint statement entitled ‘Transforming Our Justice System,’ the Lord Chancellor, the Lord Chief Justice and the Senior President of Tribunals shared their vision for the future of HMCTS, saying: “The Government is committed to investing more than £700 million to modernise courts and tribunals, and over £270 million more in the criminal justice system” (N. Holmes, June 2019; The Internet New letter for Layers).

Therefore in the UK, Her Majesty’s Courts & Tribunals Service (HMCTS) has introduced the Reform program started with digitalising the case files and online system for managing cases electronically. As of 2019 this reform program has implemented over 50 distinct projects across jurisdictions covering criminal, civil, family and tribunals in UK. The initial adoptions were payment of money claims online, applications for divorce, and appeal to Tax Tribunal. These were initially introduced as public beta versions which mean that they are fully functional and ready to use by public but still under testing. Which was a very effective way of introducing digital transformation to the centuries-old legal system in the UK.

In 2008 December HMCTS and the Society for Computers and Law jointly hosted the International Forum on Online Courts. International delegates including 200 academics, legal professionals and court reform experts discussed the challenges, successes and technological advancement made globally. This included various progress reports from England, Netherlands, Singapore, USA, Portugal, Denmark, Japan, China and India.

In 2019 inquiry was launched in to the reforms under HMCTS and “to draw the distinction between physical courts, virtual courts, and online courts, the reality is that court services of the future will be delivered as blend of some or all of these.” (R. Susskind; 2019). Further the reforms in digitalising Evidence Management Services through CaseLine Cloud based system, they manage all documentation related to legal cases and it states “Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) and HMCTS have worked together to transform the Crown Court into a digital environment, saving the CPS 29 million sheets of paper, reducing stationery costs by an estimated £2.7 million in the last year and sparing approximately 245 trees per year.” (The Crown Prosecution Service; 2020).

Digital transformation of legal systems were adopted well ahead in Singapore and integrated e-filling, e-workflow, and e-court hearing systems are some of the advancements. Also they have systems in place for complete end-to-end electronic management of case lifecycle which includes scheduling, processing, hearing, and tracking. Singapore also has adopted cross domain cooperation with prosecution, courts and prisons with real time synchronisation of information, end-to-end integration and data standardisation. Singapore is far ahead and they have implemented systems across Civil, Criminal, and Tribunal Divisions.

Our neighbouring India has adopted digitalisation early in 2009 with the introduction in Delhi High Court with a pilot e-court project for all dealings in the court of justice. And in 2012 they further extended it to electronic payment system for court fees. In 2013 the Supreme Court of India has launched a mobile app to display the case numbers heard at all court rooms at a given time. Bombay e-court project launched to accept all petitions through e-filling for company matters. And in 2014 Bangalore’s High Court was given Wi-Fi facility and the same year all 15,000 subordinate courts were transformed judgments to digital form and issued on the same day.

Further Indian Supreme Court introduced video conferencing which was expected to save Rs. 100 Cr for the Government of India. The Supreme Court introduced the new Integrated Case Management and Information System (ICMIS) intended to allow full e-filing and conducted trainings for lawyers in 2017. By 2018 India has achieved commendable results where data of 3000 court complexes available online, over 100 million cases available online, 28 million pending cases available online, 68 million orders and judgements available online.

By mid-2018 India has given digital and paperless court room facility for 342 jails and 488 district courts. And staggering 15,000 courts were facilitated under e-court mission mode project. These courts have being connected with National Judicial Data Grid (NJDG). Overall these transformations have made India favourable for businesses.

China being world’s emerging supper power has gone beyond just digitalisation and they have now deployed Artificial Intelligence judges, cyber courts and verdicts delivered on chat apps. Where they use WeChat as a platform to handle legal proceedings ‘China mobile WeCourt’. In 2017 China launched ‘cyber court,’ the Hangzhou Internet Court, where it focuses on resolving internet-based crimes which are relating to intellectual rights, online shopping, etc.

In 2018 the Beijing Internet Court was launched and after one year on its anniversary in 2019 they had accepted and heard 34,263 cases and closed 25,333 of them within the same year. And 77.7% of the cases reported that both parties did not reside in Beijing and they attended hearings through the internet. ‘According to the statistics of Beijing Internet Court, litigants’ travel mileage was thus reduced by 29.87 million kilometres and carbon emissions were reduced by 161 tons. On average, each litigant saved 800 CNY in case expenditure and 16 hours in transit’ (Guodong & Lin Haibin; Oct 2019, China Justice observer).

China has introduced many systems like intelligent trials support system, trials speech recognition system, similar case pushing system, information case handling platform for commutation and parole, and “online data integration” processing platform for road traffic disputes, and these systems support judges in improving quality and efficiency of their judiciary work. A further nationwide integrated trials management system collects and analyses court trials from all over the country in real-time.

China has also deployed blockchain technology for electronic data evidence management and there are two types of Blockchain used in the judicial system, one is public chain and the other is judicial alliance chain, where large internet companies now use to store their data so that they are accepted in court procedures. The digital readiness allowed China to transform 100% of courts to Internet Courts overnight in February 2020 due to the lockdowns of COVID-19 and maintained continuous service to the public. This is the power of digital transformation.

[The writer, MBA (PIM-USJ), ACMA (UK), CGMA (UK), ACCA Affiliate (UK), ACIM (UK), is a Financial Consultant (Virtualcfo.lk)]

To be continued