Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Thursday, 21 June 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The law of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is officially referred to as the “socialist legal system with Chinese characteristics”. The formation and development of the socialist legal system with Chinese characteristics are compatible with the basic national conditions in the primary stage of socialism; the historical process of socialist revolution; the construction, reform and opening-up of the economy; and are in line with the development of China’s productive forces and changes in the economic base.

Governing the country according to the law and building a socialist country under the rule of law is the basic strategy of the Chinese Communist Party. Forming a socialist legal system with Chinese characteristics, ensuring all aspects of the country and social life to be followed by the law is the precondition and basis of the full implementation of the basic strategy for the rule of law, and also the institutional guarantee for China’s development and progress.

The reform, opening up, and modernisation provide internal demand and motivation for the construction of the legal system and provide practical foundations and experience. The more the reform and opening up move forward, the greater the development of modernisation, the more profound the development of economic society, the more urgent it is to improve and improve the legal system, and the more stable the economic and social foundation upon which the legal system is built. It can be said that the continuous development of the socialist cause with Chinese characteristics has promoted the construction and formation of a socialist legal system with Chinese characteristics.

There are separate legal traditions and systems in the Mainland China, Hong Kong, and Macau. The legal system of Mainland China belongs to the civil law system. The legal systems of Hong Kong and Macau are based on English Common Law and Portuguese civil law respectively.

The legal systems of the Hong Kong SAR (Special Administrative Region) and the Macau SAR are excluded from the legal framework of Mainland China by the doctrine of “One country, Two systems”. The National People’s Congress (NPC) of the PRC enacted the Basic Law of Hong Kong SAR (April 1990) and Basic Law of Macau SAR (March 1993) to ensure state sovereignty and at the same time the special economic position of those two regions. Since both statutes are national laws, no local laws, including ordinances, administrative regulations and other normative documents, can violate the Basic Law.

The socialist legal system with Chinese characteristics covers laws that fall under seven categories, namely, the Constitution, civil and commercial law, economic law, administrative law, criminal law, social law, and procedural law (the law on lawsuit and non-lawsuit procedures). These seven categories of laws exist at three different levels of state laws, administrative regulations and local statutes.

Constitution

The Constitution is the fundamental law of the country. The current version was adopted in 1982 with fifth revisions in 1988, 1993, 1999, 2004and 2018. The Constitution assumes the commanding position in the socialist system of laws with Chinese characteristics and provides the fundamental guarantee of lasting stability and security, unity of ethnic groups, economic development and social progress of China. In China, people of all ethnic groups, state organs, the armed forces, political parties and public organisations, and enterprises and institutions in the country must take the Constitution as the basic standard of conduct, and they have the duty to uphold the dignity of the Constitution and ensure its implementation.

The Constitution-related law is the sum of the constitutional legal norms supporting the constitution and directly guaranteeing the implementation of the Constitution. It includes the Constitution of the National People’s Congress, the National Regional Autonomy Law, the Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. The Basic Law of the Macau Special Administrative Region, the Law of the Legislature, the Law of the Local People’s Congress, the National Flag Law and National Emblem Law, etc.

Civil and Commercial Law

At present, China does not have a complete civil code. It is based on the “General Principles of Civil Law” as the basic law, which is the first part of Civil Code in the future, also called Civil Code – General Part, supplemented by other single-line civil laws, including the Property Law, Contract Law, Tort Liability Law, Trademark Law, and Patent Law, Copyright Law, Marriage Law, etc. Commercial Law mainly includes Company Law, Insurance Law, Document Law and Securities Law.

Administrative Law

General administrative law refers to the laws and regulations concerning the general provisions of administrative subjects, administrative acts, administrative procedures, and administrative responsibilities, such as the Civil Servant Law, the Administrative Penalty Law, and the Administrative Reconsideration Law. Special administrative laws refer to laws and regulations that apply to the management activities of various specialised administrative departments, including defence, diplomacy, personnel, civil affairs, public security, national security, ethnicity, religion, overseas Chinese affairs, education, science and technology, culture, sports, medicine, and health. Laws and regulations concerning the administration of urban construction and environmental protection also form part of Administrative Law.

Economic Law

Economic Law is composed of the laws that create an equal competitive environment and maintain market order mainly include macroeconomic control laws and market regulation laws, and national macroeconomic control and economic management laws. The main laws include the Budget Law, Audit Law, Accounting Law, People’s Bank of China Law, Price Law, Tax Collection Management Law, Personal Income Tax Law, Urban Real Estate Management Law, Land Management Law, etc. Market Regulation Law mainly includes Anti-Unfair Competition Law, Consumer Protection Law, Product Quality Law, Advertising Law, etc.

Social Law

Social Law includes the Labour Law, Labour Contract Law, Trade Union Law, Law on the Protection of Minors, Law on the Protection of the Rights and Interests of the Elderly, Law on the Protection of Rights and Interests of Women, Law on the Protection of Persons with Disabilities, and Mining Safety Law, Donation Law for Public Welfare, etc.

Criminal Law

Criminal law is the law that stipulates crime, criminal responsibility and penalty, includes the "Criminal Law" revised on March 14, 1997 and subsequent amendments, and the decisions made by the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress on the punishment for crimes.

Litigation and Non-Litigation Law

This branch of the law mainly includes the Criminal Procedure Law, Civil Procedure Law, Administrative Procedure Law, Special Procedure of Maritime Litigation, Arbitration Law, etc.

The court system of China

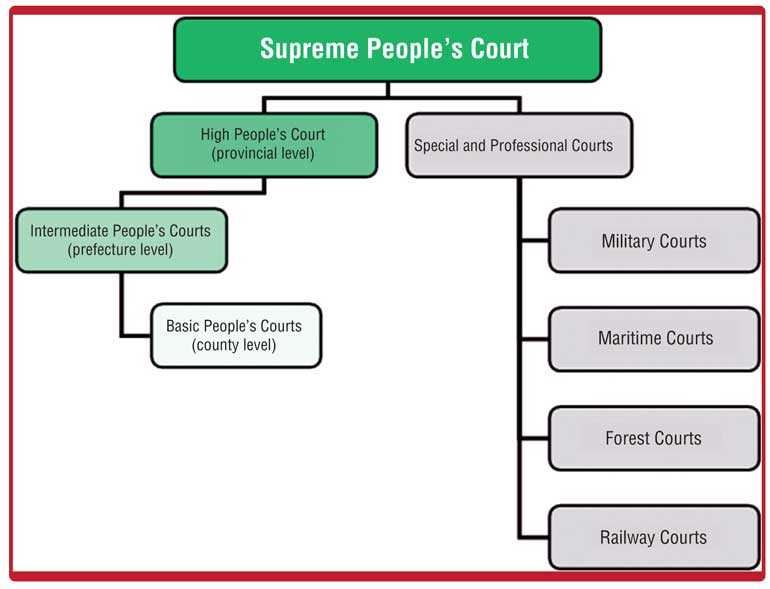

There are four levels in the court system of China: the Basic People’s Courts (at country level), intermediate, higher and supreme people's courts, in addition to special courts such as the military, maritime, railway and forestry courts.

People’s courts

Under the Organic Law of the People’s Courts (1983), judicial power is exercised by the courts at four levels:

nBasic people’s courts; also called “local” people’s courts): Courts at county or district level. Tribunals may also be set up in accordance with local conditions.

nIntermediate people’s courts: Prefecture-level courts.

nHigher people’s courts: Provincial-level courts.

nThe Supreme People’s Court (or National Supreme Court, or Supreme Court)

The highest court in the judicial system is the Supreme People’s Court in Beijing, directly responsible to the National People’s Congress (NPC) and its Standing Committee. It supervises the administration of justice by the people’s courts at various levels.

Cases are decided within two instances of trial in the people’s courts. This means that, from a judgement or order of first instance of a local people’s court, a party may bring an appeal only once to the people’s court at the next highest level, and the people’s procuratorate may protest a court decision to the people’s court at the next highest level. However, a limited number civil and commercial cases may, according to the Civil Procedure Law, be heard for the third time, a regime called trial supervision. Additionally, judgments or orders of first instance of the local people’s courts at various levels become legally effective if, within the prescribed period for appeal, no party makes an appeal. Any judgments and orders rendered by the Supreme People’s Courts as court of first instance shall become effective immediately.

In accordance with Article 11 of the Organic Law, “the people’s courts at all levels shall set up judicial committees within the courts” in order to sum up judicial experience and to discuss important or difficult cases and other issues relating to the judicial works.

Professional and special courts

Other special courts include military courts, maritime courts and railway courts. The military court, established within the People’s Liberation Army, is the relatively closed adjudication institution in charge of hearing criminal cases involving servicemen. The maritime courts are located at the major sea and river port cities. They have jurisdiction over maritime cases and maritime trade cases of first instance. It ranks equivalent to an intermediate court in the judiciary hierarchy. The railway transport court deals with criminal cases and economic disputes relating to railway and transportation.

Law-making in the PRC

National People’s Congress (NPC)

The highest legislative authority is the National People’s Congress. It has the power to revise the Constitution and create major legal codes referred to as “basic laws”. In addition, the NPC also enacts laws and decisions. Decisions may contain legal norms in the form of amendments or supplements to laws. They are often used to delegate law-making authority to the State Council.

The NPC Legislative Affairs Commission is the key organ that are responsible for the law drafting work. Since the 1990s, scholars and experts are increasingly entrusted by the NPC Legislative Affairs Commission to form drafting groups to prepare the first draft of the basic laws (for instance, this was the case for the Contract Law (1999), the Law of Rights in rem (2007), the Law of Tort Liability (2009) and the Law of the PRC on the Law Applicable to Foreign-related Civil Relations (2010)).

The State Council

The next tier of the PRC’s legislative hierarchy is the State Council which is elected by the NPC. The State Council is the head of the nation’s executive. It is empowered under Article 89 of the Constitution to “adopt administrative measures, enact administrative regulations and issue decisions and orders in accordance with the Constitution and statutes.” The State Council Legislative Affairs Office is mainly responsible for the drafting of administrative regulations which are issued for the purpose of implementing laws.

Law-making at the local level

Of the four levels of local administration in China (province, region/prefecture, county/district, township), only the provincial level possesses real law-making power. The Organic Law of Local People’s Congresses and Local People’s Governments allows congresses at the provincial, municipal, provincial capital and “quite big city” levels to enact their own regulations, called local regulations. Nevertheless, drafts of legislation must be approved by the provincial level congress before they can become law.

Official sources of Law

(a) Statutory Law

(i) Laws (fa lü): promulgated by the National People’s Congress (NPC) and its Standing Committee.

(ii) Administrative Regulations (xing zheng fa güi): promulgated by the State Council.

(iii) Local Regulations (di fang fa güi): promulgated by local People’s Congress (hereinafter Local NPC) and its standing committee.

(iv) Administrative Rules (xingzheng güizhang), including:

Local Rules (difang zhengfu güizhang): promulgated by the local governments;

Departmental Rules (bumen güizhang): promulgated by the ministries and commissions under the State Council, the People’s Bank of China, the Auditing Office, and other departments with administrative responsibilities directly under the State Council.

(v) Military Regulations: promulgated by the Central Military Commission in accordance with the Constitution and the Laws, and Military Rules enacted by the lower level military authorities within their powers and responsibilities.

(b) Judicial Interpretation

Judicial precedents are not enforceable in China. The Supreme People’s Court (SPC), however, bears the authority to issue Judicial Interpretations (sifa jieshi) as guidelines to the trials, which are nationally enforceable.

(c) Treaties

The treaties (tiao yue) China has entered are also legally effective documents.

(The writer is Associate Director/Visiting Scholar, China-Sri Lanka Cooperation Studies Centre of the Pathfinder Foundation. She is an academic at the School of Journalism and Communications of the China Southwest University of Political Science and Law and holds a Bachelor’s degree in the Science of Law, a First-class Master’s degree in Civil and Commercial Law and a Ph.D in Commercial Law. She is currently following a post-doctoral program in Economic Law. Her teaching and research interests include Intellectual Property Law, Economic Law, Media law, Financial Law and Financial Security within the Belt and Road Initiative.)