Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Wednesday, 27 July 2016 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Since 1950, a minimum of 4,200 elephants have perished in the wild as a direct result of the conflict between man and elephant in Sri Lanka. During the last 12 years, a total of 1,464 elephants were killed, along with 672 humans

The suffering of poor farmers due to invading elephants is being highlighted practically every-day in media and newspapers. According to media reports, elephants invade farmers’ cultivations, destroy crops and damage their homes.

The suffering of poor farmers due to invading elephants is being highlighted practically every-day in media and newspapers. According to media reports, elephants invade farmers’ cultivations, destroy crops and damage their homes.

Villagers demand that the Government should build electric fences to safeguard them from invading elephants. Meanwhile, environmental organisations complain of the numbers of elephants killed due to gunshot wounds as well as jaw-blasting explosives (hakkapatas) used by the farmers, and those fall into farmers’ unprotected wells and irrigation channels.

Reducing elephant population

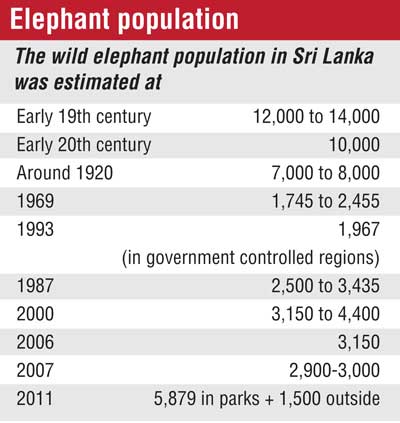

Centuries ago, elephants were widely distributed from the sea level to the highest mountain ranges. Portuguese complained of elephants approaching their fortress in Colombo in the evenings. From early 19th century, British rulers sold the upcountry forest lands for commercial plantations of coffee, and afterwards tea.

Until 1830, elephants were so plentiful, the British declared the elephant as an agricultural pest and their destruction was encouraged. The British indulged in shooting elephants as a sport and an army major was supposed to have killed over 1,500 elephants. Between 1829 and 1855 alone, more than 6,000 elephants were captured or shot. The shooting of elephants drove the remnant herds to the lowlands. Currently, there are no elephants in the hill country, except for a small herd that migrates occasionally.

By the turn of the 20th century, elephants were still distributed over much of the island. The ‘Resident Sportsman’s Shooting Reserve,’ an area reserved for the sporting pleasure of British residents, is the current Ruhuna National Park. In the early 20th century, dry zone ancient reservoirs were reconstructed for irrigated agriculture, irrigation systems were rehabilitated and people were resettled. After independence, Gal Oya, Uda Walawa, Mahaveli and other development schemes resulted clearing many thousands of acres. As a result, elephant habitat in the dry zone has been severely fragmented.

During Lanka’s armed conflict, elephants were killed or crippled by land mines. Between 1990 and 1994, a total of 261 wild elephants died either as a result of gunshot injuries, or were killed by poachers and land mines. Between 1999 and 2006 nearly 100 wild elephants were killed every year. In 2006 a total of 160 elephants were killed.

Lands for elephants

The Sri Lankan elephant population is now largely restricted to lowlands in the dry zone, east and southeast. Elephants are present in wild life reserves and a small remnant population exists in the Peak Wilderness Sanctuary. Apart from Wilpattu and Ruhuna National Parks, all other protected regions are less than 1,000 km2 in extent. Many areas are less than 50km2, and not large enough to encompass the entire home ranges of elephants that use them.

In the Mahaweli Development Area, protected areas as Wasgomuwa, Flood Plains, Somawathiya and Trikonamadu national parks have been linked to give an overall area of 1,172km2 of contiguous habitat for elephants. However, elephants in this country seem to feel shy of using corridors designed by man. Resulting, about 65% of the country’s elephants range extends outside the protected areas into human settlements and agricultural areas. It is claimed that Sri Lanka has the highest density of elephants in Asia.

The “Sri Lankan elephant” (Elephas maximus) is one of three recognised subspecies of the Asian elephant, and native to Sri Lanka. Since 1986, Elephas maximus has been listed as endangered by IUCN as the population has declined by at least 50% over the previous 60-75 years.

Domesticating elephants

Domesticating elephants

Sri Lanka has a long history of domesticating elephants – back to the times when Sinhala Kings kept them for military purposes and to enhance the majesty of their reign. Today, domesticated elephants are engaged in following work:

Feeding the elephants

An elephant consumes up to 150kg of plant matter per day. According to experts, local elephants feed on a total of 116 plant species, including 27 species of cultivated plants. More than half of the consumed plants are non-tree species as shrubs, herbs and climbers and 19% are grass. Young elephants tend to feed mostly on grass varieties. About 5 sq.km of land is needed to support an elephant in its forest habitat.

Human-elephant conflict

With the reduction of their habitats, elephant population have broken up and some herds have got pocketed in small patches of jungle. With their movement restricted, food and water sources depleted, elephants wander into new cultivated areas, which were their former habitat, in search of food and find a ready source of food and even stored paddy is not spared.

With their large size and equally large appetites, elephants can easily destroy the entire cultivation of a farmer in a single night. Therefore the farmers look upon the elephant as a dangerous pest and would rarely regret its disappearance from their area. Thus the conflict between man and elephant has become the most serious conservation problem facing the Department of Wildlife Conservation.

The ecological and social costs of clearing forests to resettle villagers have proved to be very high.

Since 1950, a minimum of 4,200 elephants have perished in the wild as a direct result of the conflict between man and elephant in Sri Lanka. During the last 12 years, a total of 1,464 elephants were killed, along with 672 humans.

Causes of conflict

The conflict between the two parties is due to the food shortage to the elephants caused by:

Reduced forest area

During the past few centuries forest area was reduced due to cultivations, depriving elephants their natural habitats. The lands consist of mountainous and valleys or rolling lands with highlands and low valleys. Over the centuries, top soil from mountains and highlands got washed off due to rain and sediments were deposited in valleys. These fertile valleys support lush vegetation and provide most food to elephants.

During the development schemes, the lands below the irrigation canals were allocated to settlers, and mountains and highlands with poor soils were earmarked as animal sanctuaries. But none looked into the ability of the high lands to supply animal needs.

The rape of the forests

Along with the reduction of forest area, the quality of forests that produced food for the elephants and other animals reduced due to human action. With the increase in human population demand for timber increased, which were obtained from the forests. Today, timbers as satin and ebony with their 200-year maturity are almost extinct.

Most hardwoods take long years to mature; they also make low demand from the soil fertility and even water. The grain patterns of their wood, a result from the dry and wet spells the tree underwent over the long growing period. Today, most popular timber varieties have disappeared from forests. While our indigenous valuable trees have disappeared, spaces they occupied were replaced by fast growing and quick multiplying thorny invasive plants, mostly imported to the country as ornamental plants. Today, most of our forests constitute of shrubs, devoid of tall trees.

Village encroachment

During colonisation, landless families were settled in development schemes. After decades, with children grown up and raising families of their own, original lands are insufficient. They encroach into low fertile valleys depriving elephants from their food supply. While villagers encroach into forests, authorities under political pressure turn a blind eye. When elephants enter their traditional lands, villagers complain and demand electric fences to keep elephants at bay. Even the elephant corridors are not safe from encroachment.

Grasslands being used by farmers’ cattle

Grass are a major component of elephant’s food and is found mostly in lands undergoing periodical floods, also reservoir beds when water levels go down. Cattle farmers have found convenient to drive their cattle into traditional elephant grasslands, depriving elephants their food.

Low forest quality

With the forests being deprived of their tall trees for human needs, their slow growth give rise to gaps being filled with shrubs. The eating habits of elephants reduce foliage of consumable plants, meanwhile non-consumables, especially thorny shrubs continue to expand. Currently, most forests are being filled with thorny shrubs.

Wildlife conservation

During the last century, Sri Lanka has established probably the widest, wildlife conservation areas in Asia. Most located in the low country dry zone, where human pressure was not serious enough to prevent the recovery of elephant numbers. The recovery was slow at first, but under the management of the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC), the number of elephants seems to have picked up.

The DWC has identified several areas where the elephant-human conflict has become serious and has adopted following conservation measures to mitigate the conflicts:

Today, conservation efforts are in full force to protect the species. Under Sri Lankan law, the penalty for killing an elephant is death.

Enforcing legislation

Although killing of an elephant could bring death penalty, never has been an occasion when a culprit was brought to court, although the entire village is aware of the gunmen and the users of ‘hakkapatas’. If the Grama Sevaka is questioned when the elephants are attacked or when forests are set on fire some control of elephant killing could be averted.

Invasive plants

While elephant numbers remained comparatively high, their food supply has decreased drastically, with the loss of their habitual grounds due to deforestation, irrigation schemes, human settlements and encroachment. Many reasons are brought out for elephant attacks on village settlement, but the most important reason is not even mentioned: the gradual reduction of availability of food (leaves) to elephants, due to widespread encroachment of mostly thorny, fast-spreading invasive plants into jungles, shrubs to low and even highlands of the country. This aspect has not been raised even by the Environmental organisations.

Amongst the invaders are giant mimosa (maha nidikumba) brought to the country on the backs of goats as food for IPKF senior staff, now are widespread all over the country. A few decades ago, Spiny bamboo (Katu una), ‘Bambusa bambos’ was planted in Minneriya Wild Reserve to provide long fibre material for the Valachanai Paper Factory. The factory never used the bamboo, but the plant has been spreading fast in the park. The bamboo does not serve any purpose and the thorns on the plant keep the elephants away.

Our entire country, jungles, shrubs, household gardens, marshes and even the Horton Plains has been inundated by invasive plants. Some of them are commonly known by Sinhala names giving the impression of being indigenous plants, for example Wel Atha “Annona glabra” originating from West Indies. From the low land opposite the Ministry of Environment to marsh adjoining Weras Ganga Park bordering Bellanwila temple are almost covered with Wel Atha and indigenous plants as Kadol have disappeared. Gandapana “Lantana camara” from W. Indies and Podisingho-maran or Eupatorium (Japan Lantana) are spread throughout the dry low country. In addition, Andara (Dichrostachys cinerea) and Giant eraminiya are widespread.

A common factor in all above are being thorny and are not consumed by any animal (except the fruit) and are fast-spreading. An indigenous plant Diyapara “Dillenia triquetra” (similar to Godapara, but shorter and grows in marshes) is fast spreading especially in the marshes and adjoining high grounds in the south and west is visible when travelling on the Southern Highway.

Settlement of conflict

The basic reason for the conflict is the shortage of food to elephants resulted from clearing of jungles, removing valuable jungle trees and plants, encroachment of low fertile valleys by villagers, taking over of natural grasslands by cattle farmers and poorly-planned elephant corridors. To prevent further complication of the problem and to avoid elephant attacks on village settlements, further encroachment of lands by farmers need to be completely stopped and the villages heavily subjected to elephant attacks need to be relocated, although the move even on encroached land would be heavily resisted by villagers and some politicians.

But the most important reason is the encroachment of thorny invasive shrubs, filling the voids created by felling of trees and clearing jungles. As these invasive shrubs are not consumed by animals, their growth continue unabated with their prolific multiplying character. These invasive plants are not confined to jungles, but have spread over the entire country. The complete destruction of these plants is an urgent necessity to safeguard our environment, agriculture and to provide food to elephants, wild animals and cattle. They are also a threat to indigenous plants, Kadol (Rhizophora mucronata) has been almost wiped out by Wel Atha. These invasive plants need to be removed and destroyed, in addition the gaps caused by the removal need to be replaced by indigenous trees, plants and grass varieties consumed by elephants.

The threat created by the invasive plants is the heaviest environmental damage the country had undergone, but was not recognised. Their eradication and the replacement with indigenous plants, would involve producing and planting millions of plants in wide variety, would be beyond the capacity of any private or Government agency. The only possibility is the mobilisation of the Government Armed Forces who would have to face a bigger enemy than the LTTE, and elimination of the enemy may take over 30 years, considering that left-over roots could reappear with the next rain. The task would be the responsibility of Minister for Environment who also happens to be the Commander of the Armed Forces.

Our President has been addressing the school children on environmental issues, now is the time to match the words with deeds. Over to you, Mr. President.