Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Saturday, 14 May 2016 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

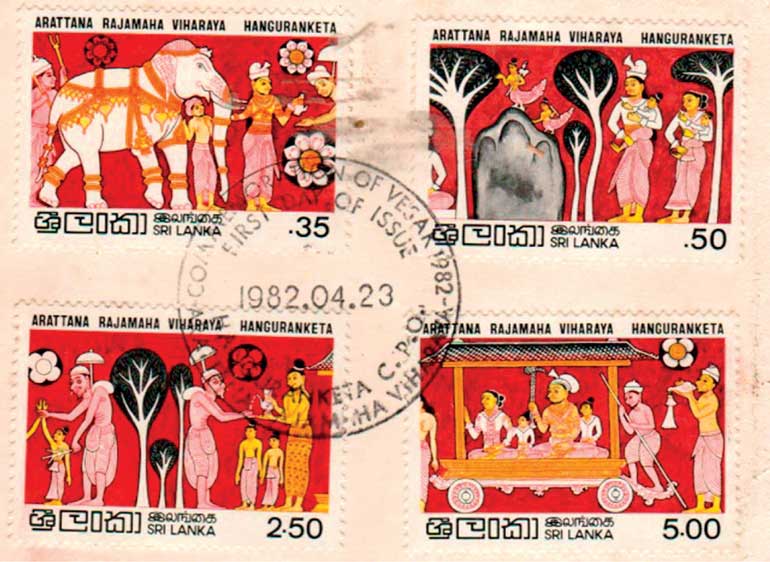

The four stamps (Vesak 1982) depict King Vessantara giving away the white elephant which, according to legend, possessed the power to bring rain; the King with Queen Madri carrying the two children walking through the Vankagiri forest having given away the Royal chariot; the two children being given; and the return of the Royal Family to the capital in a chariot after the intervention of God Sakra

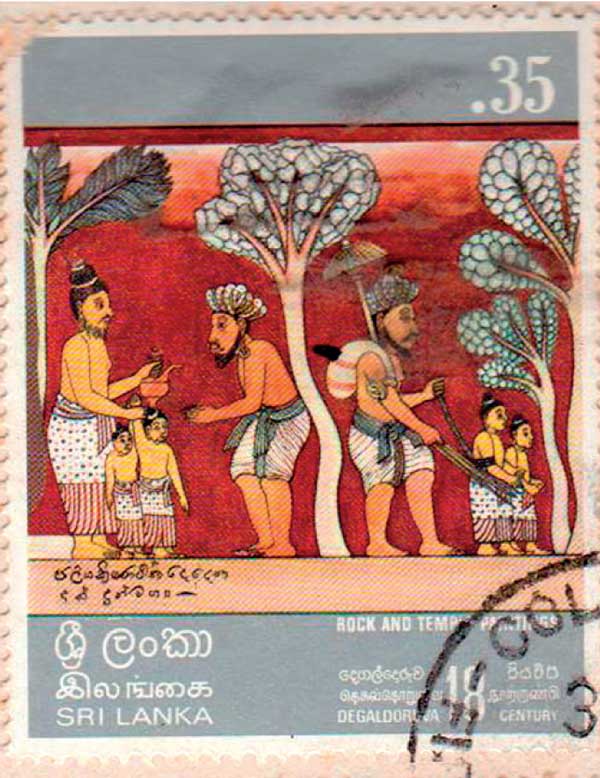

Among the 18th century paintings at the well-known Degaldoruwa Temple near Kandy is also a painting depicting a scene from the Vessantara Jataka tale. The painting shown in the stamp (1973) shows the hermit turned king giving the son and daughter and the evil-tempered Brahmin Jujaka leading them away

By D.C. Ranatunga

Walk into any Buddhist temple and you will never miss the paintings on the walls in the ‘Budu-ge’, the image house where a large statue of the seated Buddha is prominently displayed. After offering flowers before the statue and spending time chanting the stanzas seated on the floor in a corner of the image house, the devotee goes round looking at the paintings on the walls from roof level downwards.

In an era when the level of literacy was low, the devotee listened to the sermons delivered by monks in the village temple on Poya days. When devotees observed ‘Ata Sil’ – the Eight Precepts – on Poya day, an elderly layman who could read brought the ‘Pansiya Panas Jataka Potha’ where the previous births of the Buddha were narrated in story form, and read them aloud while the others listened.

It is believed that promoting piety through painting goes back the days of Emperor Asoka (3rd century BC). In a study by D.B. Dhanapala on Buddhist paintings, he states that by the time Asoka sent out his missionaries to spread the Buddhist doctrine, they were well aware of the power of art to attract people to Buddhism by showing them representations of various types of divine forms.

It is on record that when Arahant Mahinda brought Buddhism to Sri Lanka, the great emperor sent 18 guilds of artists, craftsmen and painters. The existence of an art gallery (‘chiittasala’) in Anuradhapura is also being mentioned.

In the early stages most temples were rock caves. The Dambulla Rock Temple is a good example. Dhanapala describes the concept of temple painting thus: “In painting, the rock surface or the temple wall was the canvas; religion the theme; and narrative, the objective. With his paint-brush the ‘sittara’ (artist) turned the walls into chronicles in colour in which devotees could scan the sacred stories. Art was a medium through which an exemplary life could be taught to the sinner and the sacred knowledge revived in the memory of the saint. It was primarily an attempt to present the spirit rather than the form of religion – a story rather than an idea. But this story was told as attractive a way as possible.”

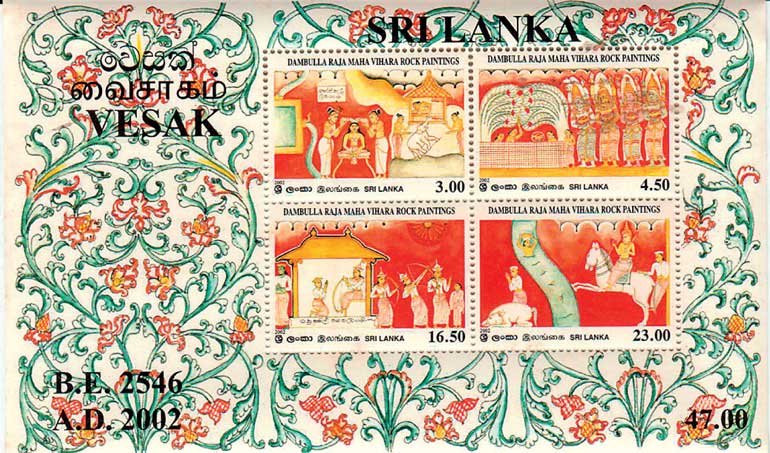

Four sections of the ‘Buddha Charitaya’ – life of the Buddha – are featured in the 2002 Vesak stamps. Starting from Queen Mahamaya’s dream (Rs. 3 stamp) of a white baby elephant with a white lotus on its trunk entering her womb after circling three times, the other stamps show the birth of Prince Siddartha (Rs. 4.50) at the Lumbini ‘sal’ grove, his skills in archery (Rs. 6.50) and his leaving the palace with Channa and the royal horse, Kantahka, crossing the river and bidding goodbye (Rs. 23)

Vesak stamps

The Vesak stamps over the years carried paintings from temples in numerous parts of Sri Lanka. While some of them were from the better known temples, others were from the not-so-well-known ones. Thus the stamps helped to create awareness of temples which had beautiful works of art by unknown painters. Names of painters and the period they were done were not mentioned anywhere. Since the stamps mentioned the name of the temple, the locations could be identified.

The subject matter of the temple paintings mainly centres on the life of the Buddha and the Jataka tales relating the earlier lives of the Buddha. A fine of the Jataka stories, the most popular is the story of King Vessantara who gave away all his belongings, the children and the queen herself. A fine example is the paintings of the Arattana Rajamaha Vihara at Hanguranketa dating back to the 3rd century BC.

The four stamps (Vesak 1982) depict the King giving away the white elephant which, according to legend possessed the power to bring rain; the King with Queen Madri carrying the two children walking through the Vankagiri forest having given away the Royal chariot; the two children being given; and the return of the Royal Family to the capital in a chariot after the intervention of God Sakra.

Among the 18th century paintings at the well-known Degaldoruwa Temple near Kandy is also a painting depicting a scene from the Vessantara Jataka tale. The painting shown in the stamp (1973) shows the hermit turned King giving the son and daughter and the evil-tempered Brahmin Jujaka leading them away.

This is yet another example of the Kandyan tradition of painting which can be seen mainly in the hill-country temples which received the patronage of the kings and identified as ‘Raja Maha Viharas’.

The Kandyan tradition was not restricted to the hill-country. Even the paintings in the south in that era indicate the same type.

Among the paintings at Godapitiya Raja Maha Vihara in Akuressa are a series depicting another popular Jataka story – the Daham Sonda Jataka – painted on an old wooden casket. Eager to listen to the Dhamma, King Daham Sonda instructs his court assistants to find someone who can preach (35cts stamp). They take off on their mission with an elephant carrying a bagful of gold currency (50 cts). The king was even prepared to jump into the mouth of a demon (Rs. 5) but God Sakra who appeared in the guise of the demon carries the king in his arms and preaches the Dhamma.

Among the paintings at Godapitiya Raja Maha Vihara in Akuressa are a series depicting another popular Jataka story - the Daham Sonda Jataka

The colours

Commenting on the colours used by the ‘sittra’, D.B. Dhanapala states that he showed a preference for different shades of yellow and red. Blue and green were used occasionally to bring out the details in a design. He attributes the preponderance of yellow and red was due to the circumstances under which the ‘sittara’ worked. His canvas was a dimly-lit cave surface and his object was to fix an image in the mind of the beholder at a glance. Thus the colours had necessarily to be brilliant in order to catch the eye in the subdued light.

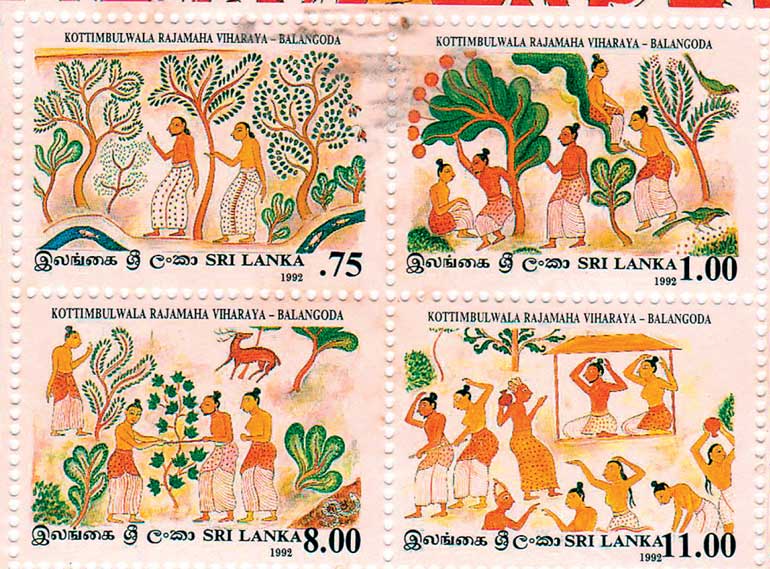

It was rather unusual to find white being used in the background in the paintings at the Kottimbulwala Raja Maha Vihara in Atakalam Korale in the Ratnapura District. The temple, with a history dating back to the days of King Valagamba in the 9th century BC, is considered to be one of the foremost cave temples with ancient paintings, which possibly may have been of later origin since the temple had been renovated by several later kings right up to the reigns of the Kandyan kings in the 18th and 19th centuries.

One of the main attractions in the temple is the image-house inside a drip-edged cave with paintings. Featured in the stamps is the Sama Jataka relating the story of Sama, a very pious person living with his parents and wife in the forest, leading a hermit’s life. The parents are blind after being attacked by a cobra.

The painter has captured in detail the parents coming to the forest (75 cts stamp), the family leading a happy life (Re. 1), Sama leading the blind parents (Rs. 8) and lamenting parents coming to the river having heard that Sama had been wounded following a shot from an arrow (Rs. 11). As the story goes, he was shot at by the king who had gone hunting and seeing the saintly Sama wanted to make sure whether he was a naga, a deity or some other celestial being. Sama was, however, saved by an unknown power and the blind parents got their sight back.

Featured in the stamps is the Sama Jataka relating the story of Sama, a very pious person living with his parents and wife in the forest, leading a hermit’s life

Dambulla paintings

Dambulla is one of the largest cave temple complexes in the South and Southeast Asian region. It is famous for its well-preserved 18th century rock and wall paintings. The murals cover an area of more than 2,000 square metres spread over five shrines. They display an enormous variety of style and subject matter.

A feature in the Dambulla paintings is the continuous narrative. A series of episodes of a single story is depicted in a linear progression with or without any separation between the individual episodes. Four sections of the ‘Buddha Charitaya’ – life of the Buddha – are featured in the 2002 Vesak stamps.

Starting from Queen Mahamaya’s dream (Rs. 3 stamp) of a white baby elephant with a white lotus on its trunk entering her womb after circling three times, the other stamps show the birth of Prince Siddartha (Rs. 4.50) at the Lumbini ‘sal’ grove, his skills in archery (Rs. 6.50) and his leaving the palace with Channa and the royal horse, Kantahka, crossing the river and bidding good-bye (Rs. 23).

In recent years there has been a tendency to move away from using temple paintings on stamps and introducing other subjects related to Buddhism but there is so much of interest in the paintings that it is a subject which must be continued to be featured in stamps.