Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Friday, 12 February 2016 00:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

In the context of a debate I am involved in regarding the inclusion of access to technology and the Internet in particular in the Constitution, I was asked what I believed should be included in, and excluded from, a Constitution.This is an answer to that very important question.

Constitutions should be short

A Constitution is the fundamental law of the land.It should be hard to enact and to change.A good Constitution should work over a long period of time, with minimal amendments.

The first of the modern Constitutions, the US Constitution, is exemplary in this regard.Since it came into force in 1789, it has been amended only 27 times. Of these, the first 10 came as a single package, and are known as the Bill of Rights.If they are considered as one, the US Constitution has been amended only 17 times in its 200-year plus history.

Containing seven articles and 27 amendments, the US Constitution is said to be the shortest written constitution in force.The original document consisted of five pages written on parchment.Even the amendments are short.

One reason for the paucity of amendments is the procedure.Not only does an amendment require approval by both houses of the federal legislature, it requires approval by a specified large number of states.But with this inflexible Constitution the country has prospered.The Constitution has achieved the status of a civic religion.

The principal reason for the success of the US Constitution is its parsimony.It addresses the most important issues and says nothing about many less-important things.

It sets out the relation between the federal government and the states.In actual fact, this relationship has changed over time because of the rising power of the executive presidency, multiple court decisions, and, of course, the Civil War.The framers of the Constitution provided the basic principles.The details have been worked out by subsequent generations.

The US Constitution defines the powers of the judicial branch and ensures that the justices who are the final arbiters of the Constitution have the requisite independence.Again, powers of the Supreme Court have been shaped by the incremental actions of subsequent generations of Justices and legislators.The details cannot be found in the five pages of the original text.

More reliance should be placed on statutes

Our Right to Information (RTI) Law is said to be imminent.While the Swedes claim precedence, one of the best known laws ensuring access to government information is the US Freedom of Information Act (FOIA).It is an ordinary statute.There is no mention of Freedom of, or Right to, Information in the US Constitution.The FOIA can be amended or repealed by the US Congress, without going through the arduous ratification procedures that are mandatory for Constitutional changes.It has worked since the 1960s.

Including details such as those that were stuffed into our 19th Amendment only creates money-making opportunities for lawyers.All they have to do is argue on the basis of inconsistencies between the language in the Constitution and statute.Over a period of time (and a judicial system that honours precedent) the interpretation should settle.But this is an unnecessary and expensive way of doing things.

To minimise the damage, all that was needed with regard to the Right to Information in the Constitution was a simple statement that “every citizen shall have the right of access to any information in the custody of a public authority or a private body as provided for by law.”All the details could have been provided for in the law.

But I go further.There is no need to include even the above language in the Constitution.It cannot be interpreted and enforced without reference to the statute and in many cases without reference also to the relevant rules and regulations.All that is achieved by including such vague language is signalling that RTI is very important.

In light of the political imperative to show that something was done regarding a promise in the Common Candidate’s manifesto, the inclusion can be understood.But in technical terms it is superfluous.If one wishes to challenge my assertion, they should try to get enforced this right provided for by the Sri Lanka Constitution today.It is unenforceable.

The details should be in subsidiary legislation

We were taught the basic principles of legal drafting in the interpretation of statutes course at Law College.But possibly because it was an optional course, the principles do not seem have been absorbed by the many lawyers who populate our legislature and even by those who do legal drafting for a living.

Put the most fundamental principles governing how the different parts of government relate to each other, how we the people delegate our sovereignty to our representatives, and the safeguards for citizens against arbitrary and capricious exercise of power by one or more parts of government in the Constitution.

Then include the principles governing specific government or other activities in statute.For example, the Evidence Ordinance and the Civil and Criminal Procedure Codes are among the most important in terms of the liberty of citizens and the maintenance of an orderly, law-governed society.The principles laid out in these laws are terribly important, but they need not be included in the Constitution.

But as any lawyer knows, the actual conduct of cases requires familiarity with, and the application of, the rules of the specific court.There is no reason to include these nitty-gritty details in either the Constitution or the Statute.These should be more malleable and are therefore promulgated as subsidiary legislation.They are not outside the remit of the legislators who we elect to represent us, but the procedures for approval are much simpler.

Is there a place for directive principles?

Directive principles were first introduced to Sri Lanka through the feudal-socialist Constitution of 1972.This Constitution centralised power in a unicameral legislature and the Cabinet selected from it.It weakened all check and balances.It emasculated the most important part of the State, the civil or administrative service.It specified fundamental rights, but also specified that they were not justiciable.It is from this disreputable source that directive principles comes from.

There is little value in including unenforceable principles in the fundamental law of the land.Better keep those for election manifestos.

There is a test for the value of directive principles.Take the wonderful sounding directive principles of the 1972 Constitution and see if they were of any help in dealing with the famine conditions that existed during the 1973-74 period, including documented cases of Kwashiorkor and Marasmus in the city of Colombo.

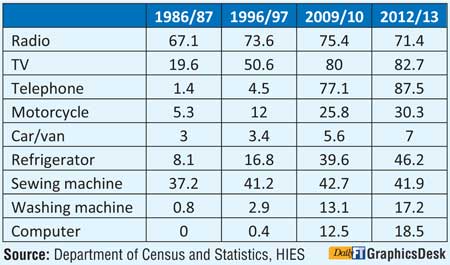

On the specific case of access to technology, let’s take the case of the record under a Constitution without directive principles on access to technology – see table 1.

Seems not bad at all.And note the decline of households with radios and sewing machines.If there was a directive principle regarding access to these technologies, would a conscientious government be duty bound to set up task forces on access to radio sets and sewing machines?