Friday Mar 13, 2026

Friday Mar 13, 2026

Friday, 12 July 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The Planters’ Association of Ceylon (PA) wishes to draw attention to the repetitive and terminal flaws advanced in two articles published in the Daily Financial Times which were authored anonymously and headlined: ‘Mendacious propaganda against workers’ demands by the Planters’ Association’ published on 20 February and ‘Plantations mafia and political path of workers’ struggle’ published alongside this reply.

The distorting lenses of Marxist economics that is flawed from the beginning

In his deeply misinformed and highly theoretical Marxist analysis of the plantation sector, the ‘special correspondent’ makes several false allegations, and even goes so far as to paint a rosy picture of a mechanised, communist utopia for the plantations sector.

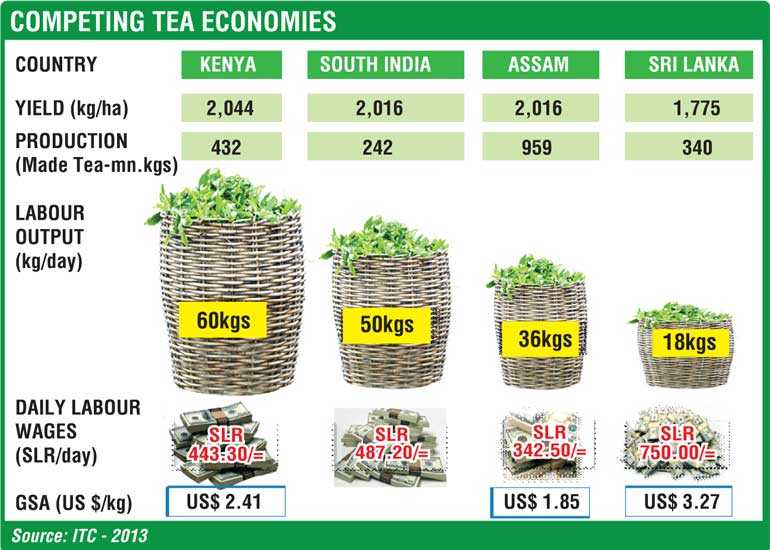

The author goes on to state with great confidence that “mechanisation of tea cultivation processes in other tea growing economies such as Kenya and Japan which led to the phenomenal increase in labour productivity and in turn created the conditions necessary to realise higher wages and profits in real terms while unit cost of production and the supply price of tea simultaneously reducing.”

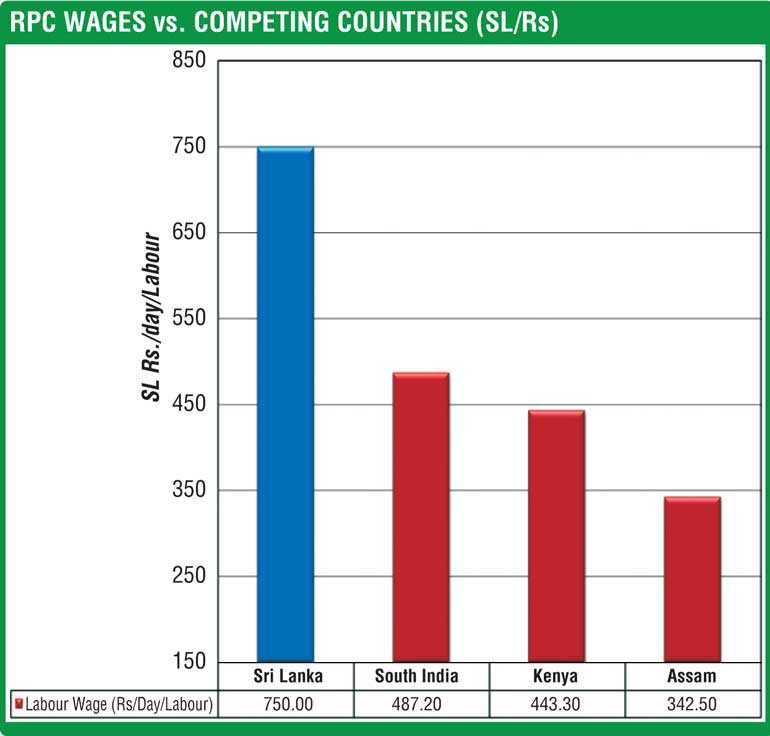

Tea harvesters in Kenya earn an average of 450 Kenyan shillings a day, equivalent to Rs. 780.7 locally. Crucially therefore the Kenyan tea harvester on average earns less per day than a Sri Lanka tea harvester who receives a total daily wage of Rs. 855 under the new collective agreement. Moreover, even under the agreement previously in force, Sri Lankan tea harvesters earned a total daily wage of Rs. 805. Quite crucially this figure too is above the earnings of the average Kenyan tea harvester.

Hence the PA is once again compelled to reiterate that Sri Lanka’s tea harvesters are the highest paid in the world still stands true, despite assertions by the ‘special correspondent’ of stagnant wages for estate workers.

Moreover, the correspondent appears blissfully unaware of concerted efforts by many Regional Plantation Companies (RPCs) to implement alternative wage models capable of not only meeting but exceeding demands advanced by politicians and segment of small but vocal activists for a Rs. 1,000 daily wage. Given that such models would necessarily be linked to productivity, they were roundly rejected by Trade Unions, despite commitments which had previously been extended.

Taking the case of RPC estates where revenue share and block-plucking models were implemented as alternatives, there are documented instances of harvesters earning between Rs. 40,000-50,000 per month on average. Naturally all attempts to expand such alternatives are blocked by entrenched stakeholders as a matter of form.

Show us mechanisation in the tea industry and we will show you flat land

In that regard, the ‘special correspondent’ also acknowledges that Sri Lankan tea harvester productivity is among the lowest in the world but claims that low productivity is purely a result of a lack of investment by RPCs into mechanisation. The author goes on to offer mechanisation of tea harvesting as the panacea for the entire industry. In doing so, the author has fixated on economic theory while disregarding practical matters like physics and biology.

The ‘special correspondent’ correctly identifies Japan as the most advanced with regard to mechanisation of tea harvesting. At present, the vast majority of tea that is harvested in Japan is enabled by large machines that are of course totally unsuitable for the sloped and terraced layout of Sri Lankan tea estates. Crucially, the tea in Japan that is hand plucked remains among the most expensive in the world.

In Kenya too there have been notable advancements in terms of mechanisation. This has not however been anywhere near the scale of Japan. Moreover, the majority of tea in Kenya is still plucked by hand. The key similarity between Kenyan and Japanese tea is in terms of geography. Flat terrain makes for easier harvesting conditions, and an extremely straightforward path to mechanisation.

It is of course common knowledge to any person who has visited Sri Lanka’s tea growing districts that the most obvious difference between Sri Lankan tea estates against those of Japan and Kenya is in the terrain. Sri Lankan RPC tea estates are found primarily on sloped land that present serious challenges with relation to the implementation of mechanisation. To take merely a trade unionist objection to such implementation, a two-man machine on sloping ground would always require one harvester to do more work and exert more energy than the other for the same pay.

Doubtless this factor alone has raised resistance to mechanisation among the very stakeholders the correspondent claims to represent. This is just one small and practical illustration of the many difficulties in adopting increased mechanisation on the majority of Sri Lankan tea estates.

At present, there are mainly only three levels of mechanisation that have been implemented for harvesting of tea at a commercial level. Specialised hand-shears, small one and two-man harvesting machines and the large machines utilised in Japan. Of these the large machines are totally unsuited to all Sri Lankan tea estates while the harvesting machines and hand shears can and have been used on some Sri Lankan estates with mixed results.

Among the most serious pitfalls of mechanisation is its potential impact on quality given that hand plucked tea is currently the only way to ensure the highest quality – a factor which is nothing less than the main feature distinguishing Sri Lankan tea from its global competitors.

Despite all of the above the ‘special correspondent’ insists that the failure of Sri Lankan RPCs to mechanise stands as proof of a sinister agenda among RPCs. He does not care that smallholder tea harvesters are facing even greater difficulties as tea prices globally have fallen. He does not care that the state owned tea plantations are falling into greater disrepair. His only focus is the RPCs – which includes the only estates in Sri Lankan that have even attempted to mechanise, and which account for just 28% of total tea production.

Disregarding the obvious contradictions in his position, the special correspondent instead embarks on a voyage of conjecture, speculative Marxist economics, and slander in the form of completely unsubstantiated accusations, which require no further response.

In doing so, the author has brazenly displayed his lack of actual understanding on how mechanisation works and the very real obstacles to its implementation in Sri Lanka as well as its impact on the quality of tea production, and the knock-on negative feedback loops such decisions will inevitably generate.

Moreover, if mechanisation was actually the “labour replacing” panacea the author claims, RPCs would quite obviously have invested accordingly, instead of spending vast, recurrent and growing sums on welfare, education, and healthcare in order to provide incentives for the retention of its dwindling labour force. Instead the author makes the ludicrous and slanderous accusation that RPCs are intentionally “stagnating production forces”, totally disregarding the fact that already the workforce has dropped substantially from where it was at the time when the RPCs first assumed management.

These dynamics occurred because of the emergence of new and essentially similar paying jobs in other sectors such as the garment factories and retail shops in urban areas which have less benefits than work in the plantation sector. Given then that the author is clearly pushing a Marxist agenda that has little to do with facts on the ground, we shift our attention to the ideology that stands at the origin of all of the author’s misrepresentations.

The hubris of equating Marxist theory with reality

Over the decades, a great deal of ink has been spilled in proving beyond a doubt why and how Marxist ideology has failed so spectacularly wherever it has been implemented. For our purposes, we will focus on the Marxist approach to agriculture as it played out in 1932-33 during what became known as the Terror Famine in Ukraine which resulted in the death of approximately 13% of Ukraine’s entire population at the time.

The famine followed agricultural collectivisation at the end of the 1920s, a formally voluntary process that was in fact coercive in its implementation. Along with forced and rapid industrialisation, it was part of a package of modernisation policies launched by Stalin in the first phase of his leadership.

Industrial growth needed to be financed by grain exports, which collectivisation was supposed to facilitate through compulsory state procurements and non-negotiable prices. The problem was how to get the grain out of the countryside. The state – which now claimed to represent purely the interests of the working class – did not know how much grain the working class farmers in the Ukraine actually had, but suspected that much was being hidden. An intense tussle between the state’s agents and farming peasants over grain deliveries ensued.

In the interim, the Soviet leaders had worked themselves and the population into a frenzy of anxiety about imminent attack from foreign capitalist powers. In Soviet Marxist-Leninist thinking, “class enemies” within the Soviet Union were likely to welcome such an invasion; and such class enemies included “kulaks”, the most prosperous peasants in the villages – the majority of which had achieved their prosperity through their own hard labour. Thus collectivisation went hand in glove with a drive against kulaks, or peasants labelled as such, who were liable to expropriation and deportation into the depths of the USSR. Resistance to collectivisation was understood as “kulak sabotage” Ukrainian officials, including senior ones, tried to tell him that it was no longer a matter of peasants concealing grain: they actually had none, not even for their own survival through the winter and the spring sowing. But Stalin was sceptical of people who he deemed to be “class-enemies” and discounted their explanations and warnings on principle.

This is how Marxist economics works in practice because Marxist economics is not based on reality; rather in ideology and therefore totally blinded to facts which contradict its agenda. It masquerades as one of uplifting worker living standards but this is merely justification for knocking down established institutions in order to take control of valuable resources and thereby gain power, only to inevitably run themselves and their followers into the ground.

This very cycle has already played out in Sri Lanka’s own history as well as the history of all other nations that ever committed themselves to a Marxist worldview – the exception being China, which has essentially adapted into hybrid capitalist model.

A carnival of accusations and not a workable solution in sight

These dynamics are perhaps best embodied in the ‘special correspondent’s’ claim that: “the percentage rate of higher price received by Sri Lanka’s tea over and above rest of the world is not an entrepreneurial income, it is ‘unearned’ as Ricardo would claim and therefore cannot be identified as a category of profit.” Hence he claims that RPCs essentially serve no purpose, given that RPCs are merely ‘landowners’ that do not contribute labour or effort, hence their income is ‘unearned’. He falsely claims that RPCs have intentionally stagnated production because they invest in fertiliser and not mechanisation. He goes on to openly disregard all established laws and common sense related to companies, and attempts to equate RPCs with tea exporters – all of which are merely landowners who benefit from income they have not earned. In the process he totally ignores the extensive and complex knowledge required to successfully maintain a tea estate at optimum conditions. These factors include the precise timing with regards to fertilising, harvesting, and the various other timely agricultural practices, in addition to specialised processing and packaging of tea in order to preserve quality.

He ignores the legal and commercial expertise necessary to package and market tea in overseas markets which exporters bring to the table. The author essentially dumbs down that all of the value added across the supply chain as being purely a product of labour and totally ignores the knowledge, technical skills, planning and resources necessary to orchestrate productivity across the entire supply chain.

Feeble calls for revolution and communist utopia

Where the author deviates from stereotypical Marxism is only in stopping short of calling for forced appropriation of the “means of production” through forced collectivisation of labour and violence.

Instead, he calls for the “reorganisation of production relations in an egalitarian manner’ - certainly a more palatable euphemism but in proud Marxist tradition, blissfully short of the details necessary to ensure that we do not suffer a similar fate to Ukraine’s agricultural production in 1932.

As the ‘special correspondent’s’ nonsensical rant comes to its conclusion, his Stalinist underpinnings begin to show, as he goes on to hypothesise about how: “the left should pose itself the question whether we allow this outmoded destructive feudal mafia to continue their plunder unharmed…”

He then calls on workers to use “political” means to “revoke the legal rights of the Licensed Export Firms to purchase from tea auctions and entrust it upon a body of workers’ conglomeration which will in turn decide: 1. the selling price taking into account the prevailing world market prices 2. the rate of wages 3.the spheres of reinvestment of the surplus which encompasses industrial training, political education and cultural development of the workers.”

Because according to him, the best people to manage everything from the planting and replanting to plantation economics, transportation and logistics, packing, branding and marketing, negotiation of shipping, sales and insurance contracts, and of course international marketing, promotion and sales should be the worker, who in turn will be represented directly by a state run presumably by workers. In short. Nationalisation. Again. Because as it often repeated: the definition of insanity is repeating the same actions and expecting different outcomes. Given that Marxists are remarkably absentminded when it comes to history, the PA therefore reminds readers to remain open to the lessons of history. In the meantime the author claims that “the initial task is to educate the workers on the disingenuous propaganda spread by Planters’ Association and reveal the possibility of raising wages while the industry remaining profitable”. Given that mechanisation – at least as affairs stand today – is demonstrably impractical we call on the ‘special correspondent’ to further elaborate on how wages can be raised without further hurting sustainability of the business and ultimately productivity.

Contd on page 21

Planters’ Association....

This is so even in the midst of a global downturn in tea prices in all major tea producing nations including in Japan, Kenya, China, India, and anywhere else the author chooses to identify as a tea harvesters utopia. Given that the author has acknowledged that the measures he has proposed are “not possible within the present legal framework”, we also call on the author to explain how their goals will be accomplished without breaking further laws over and above those related to slander and defamation.

Despite all of these challenges however, the PA reiterates that its members have invested in mechanisation where possible and while they have encountered real obstacles, they continue to seek out methods for adapting such technologies to the extremely specific requirements of domestic conditions. The PA therefore welcomes any pragmatic inputs – be they from scientists or even Marxist economists – capable of leading to the development of feasible and financially viable solutions to the challenge of mechanisation on the slopes of Sri Lanka’s tea estates.