Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Friday, 12 July 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By a Special Correspondent

In an earlier account published by Daily FT (http://www.ft.lk/agriculture/Mendacious-propaganda-against-workers--demands-by-the-Planters--Association/31-673130), we exposed the vested interests of Planters’ Association’s claim that tea estates are currently more or less loss making and therefore a wage increase of up to Rs. 1,000 a day demanded by workers would ruin the industry.

It was shown that Planters’ Association rests its argument against the workers’ demand on two main postulates. First postulate popularises the myth that plantations sector revenue depends on Sri Lanka’s tea auctions’ price (Rs. 581.58 per kg in 2018 – CBSL) while in reality, the sector revenue changes according to tea export price (Rs. 820.75 per kg in 2018 – CBSL) in global markets. Latter in general is over 40% above the former which is evident from above figures.

Second postulate states that labour productivity of Sri Lankan workers is sharply below that of other tea producing countries due to their inefficiency and lethargy. Therefore, low wages in Sri Lanka according to the planters is to be blamed on workers themselves.

We elucidated that rather than workers’ love for idleness it’s the mechanisation of tea cultivation processes in other tea growing economies such as Kenya and Japan which led to the phenomenal increase in labour productivity and in turn created the conditions necessary to realise higher wages and profits in real terms while unit cost of production and the supply price of tea simultaneously reducing.

Hence, we illustrated that by shifting the surplus generated in the sector outside itself into conspicuous luxury consumption and speculative investments, the planters coupled with licensed export firms deliberately stagnate the production forces and therefore maintain the colonial mode of exploitation even in the absence of colonial rule. In this light the above article is a necessary preamble to meaningfully connect with the proceeding argument.

Structure of market forces

In the following account we will explore the structure of the market forces or exchange and production relations which objectively impel the planters to reproduce itself in the guise of a feudal landlord class, destroying the surplus generated in the sector on scandalous luxury consumption and speculative investments, while production forces and the lives of the direct producers eternally stagnate. This is to say that we will explore the conditions which prevent the transformation of Sri Lanka’s feudal elite to a modern bourgeoisie within the restricted context of plantations. In the light of this we will explore the specific political path the workers should necessarily tread.

Absence of capital accumulation in the plantations sector by redeploying the surpluses in labour replacing machinery in the cultivation process emanates from the nature of the relationship the plantation sector establishes with world trade and the indentured nature of the labour force ossified into a distinct cultural unit from the community outside.

Before further exploring the reasons into deliberate stagnation of production forces under the planters’ aristocracy, we may look into the structure of capital deployed in plantations by disaggregating the difference and relationship between labour and land productivity in agriculture.

It can be observed that apart from the wage bill of the plantations, the predominant form of capital usage is in the application of fertiliser and hence working capital dominates the composition of capital as opposed to fixed capital in the form of machinery. It needs to be borne in mind that application of fertiliser increases land productivity (per acre yield), which in turn increases aggregate output while output per worker or productivity of labour remains unchanged. This is so given that increased land productivity increases aggregate output and consequently, more workers are required in the harvesting process in proportion to the yield increase. Output per worker or productivity of labour therefore remains more or less unchanged while productivity of land increases through application of fertiliser while workers required per acre rises concomitantly.

Hence, increase in land productivity does not reduce the unit cost of production and hence does not augment the price competitiveness of plantations. Although productivity of labour and unit cost of production remains unaltered with increasing land productivity, aggregate profits increase with the rise in output achieved through increased yield per acre. This indicates that nature of capital deployment in plantations is not shaped by price competition in the world markets. If so the redeployment of capital would be also absorbed by labour replacing machinery which in turn would simultaneously increase land and labour productivity while unit cost of production and supply price decline and wages and profits rise in real terms.

In the same vein it needs to be pointed out that increased labour productivity through introduction of labour replacing machinery, as opposed to capital infusions enhancing land productivity, will cause the aggregate output to remain unchanged while simultaneously increasing the per worker output or productivity of labour. The unit costs of production and supply price therefore decline coupled with rising wages and profits in real terms. This means to say that there is a dialectical relationship between labour and land productivity peculiar to agriculture, a key characteristic which distinguishes the latter from the dynamics of non-agricultural sector.

Increasing land productivity while labour productivity remaining unchanged due to domination of working capital in the capital composition of plantations in turn erect conditions which enable the growth of profits while real wage rate stagnates. This is so given that wage rate cannot be increased beyond its productivity which is not altered by land productivity enhancing capital infusions. It means to say that in Marxian terms the mode of capital formation causes the rate of surplus value to remain unaltered.

Consequently, the surplus is materialised in its absolute form as opposed to its relative form. Hence, extension of the working day in the absence of a corresponding wage payment remains the only method of augmenting the rate of surplus value which is widely employed by the planters and also in most other sector in the economy in general. This means to say that the rate of surplus value is high in Sri Lanka’s plantations while the mass of surplus value generated by a worker is low compared to an industrially transformed plantations, for instance in Japan.

This is to say that the structure of capital formation in Sri Lanka’s plantation sector is determined by its noncompeting relationship established with rest of the tea producing economies in world trade. This is in fact what Adam Smith meant in his discussion on ‘vent for surplus’, that foreign trade is the lever that shapes division of labour in economic activity and therefore productivity of labour rather than a means of earning foreign exchange as popularly held. In the case of Sri Lanka’s exports in general and tea in particular this expected outcome has not materialised. Uncovering the reasons for this peculiar state of affairs with regard to Sri Lanka’s plantations is one of two main objectives of the proceeding discussion.

Price received by Sri Lanka’s tea

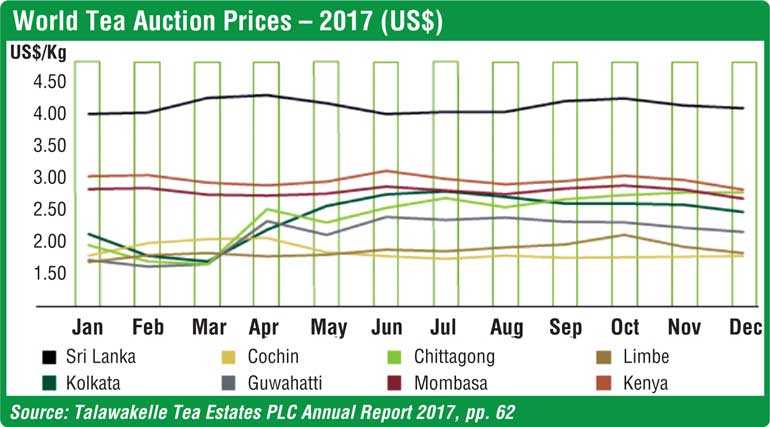

The fact that price received by Sri Lanka’s tea in world markets is approximately double that of world average price excluding price of Sri Lanka tea indicates that Sri Lanka is immune to forces of price competition from rest of the world and the product is differentiated (see the figure). This is owing to the belief that Sri Lanka’s tea is unique in flavour, aroma, etc., and therefore receives a premium price over and above other world producers.

Hence the nature of product’s relationship with world trade remains monopolistic. The indifference curve of Sri Lanka’s tea and that of rest of world is therefore convex to the origin indicating that to maintain the same utility along the curve consumers are willing to sacrifice more of tea from rest of the world to consume a comparatively lesser volume of Sri Lanka’s tea.

This is to say that Sri Lanka’s tea due to its unique geographical qualities remain naturally protected from price competition in world markets. Hence, alterations in the capital composition of the sector in a way that reduces unit cost of production will not be forthcoming through interaction of market forces.

Surpluses are therefore reinvested in the sector in the form of working capital dominated by expenses on fertiliser which in turn raises the land productivity and aggregate output while labour productivity and therefore unit cost of production remain unchanged. This peculiar structure of capital formation or production relations determined by the specific exchange relations the sector has weaved itself into world trade provides the groundwork for increasing aggregate profits while the wage rate stagnates in real terms simultaneously.

In this light it should be clarified that the percentage rate of higher price received by Sri Lanka’s tea over and above rest of the world is not an entrepreneurial income, it is ‘unearnt’ as Ricardo would claim and therefore cannot be identified as a category of profit. The nature of this income precisely overlaps with Ricardian concept of rent or rather the concept of ‘Differential Rent I’ proposed by Marx by further developing Ricardo’s formulations. Differential Rent I is the higher income gained by employing an equal amount of capital in two or more identical units of production under the same method of production.

With regard to Sri Lanka’s tea exports, the Differential Rent I is the price differential between Sri Lanka and rest of the world. The concept was formerly applied by late Dr. S. B. D. De Silva to understand the structure of incomes in Sri Lanka’s tourism sector and we are herewith extending the same to the plantations to elucidate the nature of its incomes.

Indentured nature of the plantations workforce further impels the planters to sustain the current form of capital formation dominated by working capital. Fixed capital currently employed in the sector is in the form of workers’ housing, schools and medical facilities and so on and not in the form of machinery designed to aid the labour process in the estates.

Introduction of labour replacing machinery in this setting, would therefore render the fixed capital investments into providing workers’ infrastructure or rather, investments into imprisoning the worker to the estate, redundant, while its breakeven time is long drawn out (see De Silva, S. B. D, 1982, 2011, ‘Political Economy of Underdevelopment’, Routledge, London). This particular phenomenon where labour is retained by subjugating it into an indentured work regime repels labour replacing capital infusions into the sector.

Further, it can be observed that since 2008/09, level of maintenance and replanting in the Regional Plantation Companies (RPCs) were declining. This can be attributed to the opening up of new speculative spheres following the ending of the war which would yield quick returns such as property development, stock trading, tourism and so on.

Given that Sri Lanka’s tea is established as a world renowned product with unique qualities and therefore occupies a monopolistic position in world markets as explained earlier, the extent of reinvestment into the sector can be relaxed to a certain extent and the funds can be transferred into other emerging speculative areas without losing the market share of tea at the global level. This can be cited as the main reason why investments that would improve land productivity itself let alone labour productivity, were neglected during last ten years as highlighted by many concerned entities including trade unions.

Fictitious division between RPCs and Licensed Export Firms

Another important phenomenon that prevents not only the reinvestment of plantation sector surpluses within itself but also the workers’ demand to raise daily wage up to Rs. 1,000 while the aggregate surplus generated by the sector is more than sufficient to do so hand in hand with the industry remaining profitable (which we demonstrated in our previous account), is the fictitious division between RPCs and the Licensed Export Firms that operate through the auction process.

As we elaborated in our previous account the profits of the sector is appropriated within the licensed export firms given that their contribution margin ratio is determined by the difference between the export price and the auction price. Contribution margin of RPCs is determined by the difference between unit cost of production and auction price of tea which is significantly low compared to the gains of licensed export firms. Therefore, approximately 80% of the profits of the sector is appropriated within licensed export firms while both the latter and RPCs are mainly owned by large conglomerates such as Aitken Spence PLC, MJF Holdings Ltd., Vallibel Plantations Management LTD, Richard Pieris & Co, James Finlay Plantation Holdings (Lanka) Ltd., Sunshine Holdings PLC, Hayleys PLC, etc.

Owning both RPCs and Licensed Export Firms by a single entity is illegal as per Sri Lanka Tea Board. This means to say that siphoning away of plantation sector surplus from itself is established at the level of accounting and cannot be reversed within the exiting legal framework which would enable the realisation of workers’ demands. It is impossible to retransfer the surplus appropriated within the licensed export firms into RPCs books through legal accounting practices. Hence realisation of workers’ demand for higher wages up to Rs. 1,000 per day is impossible within the existing legal framework.

Path of the workers’ struggle

In this backdrop what should be the form of workers’ struggle that would ensure their emancipation from the yoke of feudal aristocratic mafia?

Let us first reflect on the origin of the demand for a Rs. 1,000 daily wage. This was initiated by Ceylon Workers’ Congress (CWC) Leader Arumugam Thondaman and was not a battle cry instigated by the workers. In January 2019 a bogus settlement was reached between the prominent workers’ unions and the RPCs which ended up workers receiving an increase of Rs. 50 per day.

Since then the CWC which initiated the demand for Rs. 1,000 daily wage, withdrew from demanding it. The strength of the workers struggle consequently faded faster than it came to being. The minority of workers who continued to protest and demanded Rs. 1,000 were then branded as traitors by the same party leadership which initiated the demand.

There are two key occurrences in this progression of events that require explanation. First, what was the motive of the CWC in initiating the demand for Rs. 1,000 daily wage at this particular moment and the reason for abruptly withdrawing from it without realising any meaningful progress? Secondly, why did the urgency of the workers decline as soon as the CWC withdrew from representing the demand?

We may initially attend to the first concern. The warm and fruitful relationship maintained between the CWC leadership and planters and their mutual understanding is well known. There can be hardly any doubt that the CWC leadership required their periodic ransom from the planters for keeping the workers in line without them posing a threat to interests of both CWC and planters. In this context the CWC simultaneously plays the role of workers’ representatives and pretends to address their need for receiving a subsistent wage which in turn ensures the obedience of the workers to the party leadership.

Hence, when the concealed demands of the CWC were met by the planters and the workers were convinced that the Rs. 1,000 daily wage cannot be paid without ruining the plantations as perfidiously preached by the Planters’ Association, the CWC leadership withdrew from the initial demand without a trace of indignity. All that mattered was their interests were secured.

The decline in workers’ urgency towards the struggle is emanating from their belief that if daily wage is increased to Rs. 1,000 the plantations will be bankrupt and will ruin their only means of livelihood. Hence, the ideological hold that the Planters’ Association yields over workers with the shameless assistance of the CWC succeeded in creating a feeling of guilt, preventing workers from fervently representing themselves. Therefore, the initial task is to educate the workers on the disingenuous propaganda spread by the Planters’ Association and reveal the possibility of raising wages while the industry remaining profitable. This will replace their guilt with indignation.

In this light the left should pose itself the question whether we allow this outmoded destructive feudal mafia to continue their plunder unharmed. The main political demand of the workers therefore should be to revoke the legal rights of the Licensed Export Firms to purchase from tea auctions and entrust it upon a body of workers’ conglomeration which will in turn decide 1. the selling price taking into account the prevailing world market prices 2. the rate of wages 3.the spheres of reinvestment of the surplus which encompasses industrial training, political education and cultural development of the workers.

The programme should therefore aspire to establish a symbiotic relationship between plantation agriculture and industry which will in turn shift the composition of the workforce from unskilled to skilled scientific work enabling the growth of communist relations within the yoke of underdevelopment. The workers should not be humiliated by having to beg for a living wage from a scandalous aristocracy plundering wealth of the nation; the workers are capable of shepherding their own destiny.

Capital in Sri Lanka’s plantation sector exists in the form of commodity capital and not in machinery or land in a significant way. Power therefore rests with those who acquire the commodity capital and not capital in the form of means of production. Hence, workers’ demand should not be the appropriation of means of production, but entrusting the right to purchase the output of RPCs on a workers’ collective and revoke the legal rights of the Licensed Export Firms to purchase from auctions. The production relations should then be reorganised in an egalitarian framework.

Initial capital required for the council to purchase RPCs’ output should be provided by the State in the form of an advance that will be repaid with interest. Reinvestment of the surpluses should initially flow into mechanisation of the harvesting process and shifting the surplus labour into producing the said machinery and other ancillary inputs of the tea industry. A somewhat similar movement was formed in Yunnan Province in China prior to the Chinese revolution.

This will enable a phenomenal rise of real wages while the industry remaining price competitive in world markets as the surpluses that were siphoned away from the sector since its inception two centuries ago, will then reverse its flow back into the system. The movement has the possibility of emerging as a nucleus of an emancipated region and its success will provide a model that could spread beyond its initial limits. Devotion to the ruling ideology cannot be defied while its material basis remains unchanged.